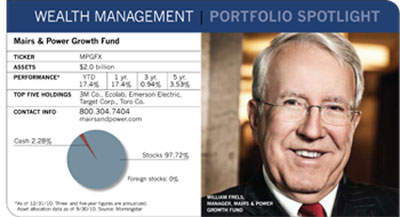

When Judy Garland closes her eyes and chants "There's no place like home," she could well be talking about the investment philosophy behind the Mairs & Power Growth Fund. Launched in 1958 by St. Paul, Minn., native George Mairs Jr. as a way for smaller investors to access the stock market, the fund zeros in on companies of all sizes, many of them in its own backyard.

"The upper Midwest is home to a surprising number of attractive growth companies, and many of them are in the Fortune 500," says fund manager and longtime Minnesota resident William Frels. "We couldn't implement this kind of geographic strategy in Detroit or Cleveland." About 60% of assets are attributable to companies in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area and the upper Midwest, with the rest spread in companies throughout the country.

To Frels, nothing is quite as effective as being in the thick of things, especially in the small- and mid-cap space. "When you're working outside of a region, you don't have any expertise beyond what you see in financial reports," he says. "Because we're neighbors with the companies we invest in, we talk to management all the time and see firsthand what's going on."

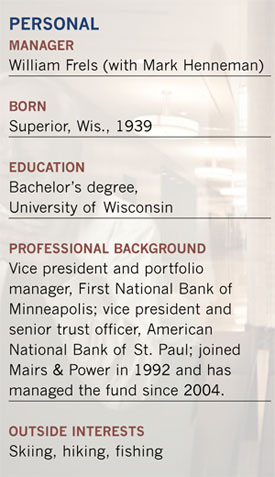

Born in Wisconsin in 1939 and a 1962 graduate of that state's university campus in Madison, the 72-year-old manager has schmoozed and badgered local company managers for almost half a century. After working at two Twin Cities area banks as an investment officer, he joined Mairs & Power in 1992. He became the fund's co-manager in 1999 and succeeded longtime manager George Mairs III in 2004.

Frels describes Minnesotans as people who are "conservative, stable and don't tend to move too much." The same could be said for the fund's stocks, some of which have been in the portfolio since before Garrison Keillor's tales of Lake Wobegon lured nostalgia-starved listeners. Over the last three years, the fund's annual turnover rate of less than 5% has been one of the lowest in the industry.

While such loyalty may seem dated in an era of rampant market volatility and computerized trading programs, Frels has no plans to change his strategy. "I refute the argument that buy-and-hold investing is dead," he says. "Traders compete for short-term gains in the stock market against powerful competition and work in an imperfect market environment. Their odds of success are low."

One of the first companies he recommended for investment after he joined Mairs & Power was Donaldson Co., a firm whose managers he became familiar with during the 1960s before it went public. Based in Bloomington, Minn., Donaldson was a growing presence in the air filtration business in the early 1990s. Today, it's one of the leading providers of filtration systems in the world and one of the fund's largest holdings. Even though Donaldson is an industrial company, its business has seen strong secular growth over the years and should continue to do so, says Frels.

An even longer-term holding, Target, was born in the 1960s as Dayton's, a now defunct chain of department stores based in Minneapolis. Dayton Corporation opened the first Target store in 1962 to compete with Kmart in the discount arena, and the new brand grew rapidly. The parent, which later became Dayton-Hudson, changed its name to Target in 2000.

"In terms of quality and price, Target is the only mass merchandiser that can effectively compete with Walmart for discount shoppers, and it offers a more upscale shopping experience," he says. "That worked against it in the depths of the recession. But now that consumer confidence is improving, I think people will look beyond just getting the cheapest prices."

With fewer than 50 holdings and a heavy concentration in basic industries and capital goods, which together account for around 30% of assets, the fund takes a fairly concentrated approach. It also eschews energy stocks, an important component of many large-cap funds, because the earnings of those companies are somewhat unpredictable.

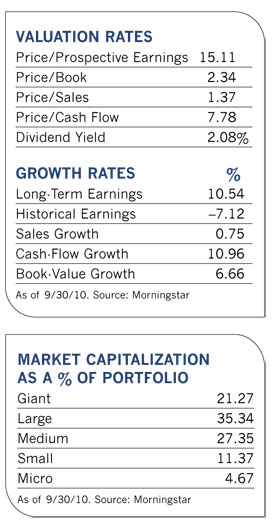

Although Morningstar categorizes it as a large blend fund, small and mid-size companies make up a key element of its portfolio. Companies with over $5 billion in stock market value, which Frels defines as large caps, account for 55% of equity assets. Mid-caps with between $1 billion and $5 billion account for another 40%, and small companies come in a distant third.

"In this region, there are more small and mid-cap names we find attractive, so that's where we focus most of our new purchases," says Frels. "Our larger company holdings are more geographically diverse." He believes that although small and mid-cap stocks are expensive relative to large caps, their superior growth attributes will allow them to outperform over the next three to five years.

One small company holding, Eden Prairie, Minn.-based Stratasys, was added to the portfolio in 2009 after conversations with management convinced Frels that the company's three-dimensional printer and production systems were unique to the industry and an effective tool for developing prototypes more quickly. The company recently signed a distribution deal for its products with Hewlett-Packard.

An overweighting in small- and mid-cap stocks relative to its peers in the large-blend category has helped the fund pull ahead of the pack, according to Morningstar analyst Josh Koeck, and over the last ten years it has performed better than 98% of such funds. While the focus has worked in its favor over the long term, Koeck cautions, it can also lead to periods of underperformance when large-cap stocks pull ahead.

Frels says the conservative leanings of the fund, which emphasizes companies with strong, predictable earnings and solid balance sheets, means that "our stocks will rarely outperform in a strong market. But they usually hold up better in poor or mixed market environments." Those assertions held true both in the bear market of 2008, when the fund performed over 9 percentage points better than its category peers, and in 2009, when it underperformed them by 5.65 percentage points.

As 201l begins, Frels says prospects for the stock market remain "quite promising, considering the outlook for corporate earnings together with the historically low level of interest rates. Dividends yields for many companies are higher than bond yields, which suggests stocks are still cheap."

Another measure, earnings yield, also appears reasonable compared to bonds. An earnings yield is the reciprocal of a price-earnings ratio. So if a stock trades at 20 times earnings, it has a 5% earnings yield (1 divided by 20).

"Ten-year Treasuries are yielding around 3%, while the earnings yield for stock is around 7%. That's wide by historical standards," he says. "Stock valuations aren't in the bargain bin, but they're still quite reasonable, especially when you compare them to bond interest rates."

While rising interest rates would throw a wrench in the equation by making bond yields more attractive by comparison, Frels says continued high unemployment and housing market troubles make it unlikely that the Federal Reserve will allow rates to rise significantly. At the same time, with signs of moderate growth throughout the economy, he does not see the U.S. falling into a double-dip recession.

A saving grace for the economy will be growth in emerging markets and the benefit that U.S. companies will reap from it. Longtime holding 3M, for example, derives one-third of its sales from those markets. Based in St. Paul, the company behind Post-it notes, Scotchgard, Nexcare Bandages, Thinsulate, and other products expects developing markets to account for 45% of sales by 2015.

Another holding, Emerson Electric, has been a beneficiary of the market's focus on cyclical industrial companies that stand to benefit from an improving economy and higher capital spending. Headquartered a few miles from Frels' office, Patterson Companies has grown to become the second-largest distributor of dental supplies in the country and is increasing its presence in veterinary supplies as well.

At 18% of assets, health-care represents the fund's largest sector weighting. Frels points to longtime holding Medtronic as a "major disappointment over the last several years." The medical technology company, whose products include pacemakers, defibrillators and insulin pumps, has had difficulty overcoming investor concerns about loss of health-insurance coverage with high unemployment, as well as uncertainty surrounding medical reimbursement under the new health-care mandates. The company also has a number of new products awaiting FDA approval, which Frels suspects are being held up as the federal government tries to avoid expensive new treatments for Medicare patients. Other holdings in the sector, such as Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, face patent expirations and more competition from generic products.

But the tide of aging baby boomers needing drugs and medical equipment will eventually prove powerful enough to overcome what he considers such short-term investor concerns. And almost as surely as Minnesota winters are cold, the fund's manager will wait patiently for that to happen.