Low U.S. interest rates and a stuttering stock market are hitting corporate pensions hard, but instead of boosting contributions some companies are taking advantage of a new regulatory rule that allows them to contribute fewer dollars now and make up the difference later.

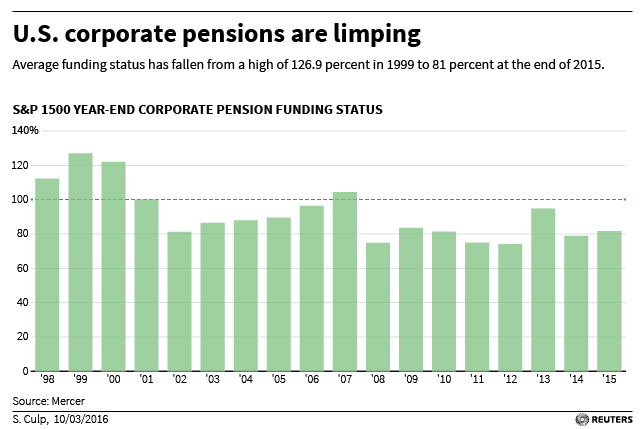

The average pension among companies in the S&P 1500 was funded at just 78.1 percent of its liabilities at the end of February, down from nearly 95 percent in late 2013, according to the most recent numbers from human resources consultant Mercer, a part of Marsh & McLennan <MMC.N>.

At some companies, the funding levels are much lower: the pension plan at Delta Airlines Inc <DAL.N>, which has the worst funding status among large corporate pension plans, only has enough assets to cover 45.4 percent of its pension obligations.

In September 2015, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission decided to allow companies to adopt a different way of measuring their discount rates, which can bring the immediate funding needs down. The only problem with this way of seeking relief is that their longer-term obligations remain the same, according to David Zion, a veteran accounting and pensions analyst at Credit Suisse.

So far, 19 companies in the S&P 500 have either adopted or are planning to adopt the new so-called spot rate approach, Zion said. They range from auto parts retailer Autozone Inc <AZO.N> to media company Walt Disney Co <DIS.N> and tractor maker Deere & Co <DE.N>. The savings vary, with telecom giant AT&T <T.N> saying that it expects to get a $1 billion pre-tax boost to its bottom line while Disney expects a $137 million reduction in costs, both in the current fiscal year.

The plans concerned are usually what are known as defined benefit plans. Many companies now only offer 401K defined-contribution plans that are largely funded by employees rather than their employers and therefore don’t create such corporate obligations.

Many of the companies that have legacy defined benefit plans are older companies in industrial businesses, particularly manufacturing businesses whose workers belong to labor unions.

Federal law requires a company with an underfunded pension to eventually make additional payments into their plans to make up the difference, rather than requiring retirees to accept fewer benefits.

The main culprit behind the dramatic decline in funding levels is exceptionally low interest rates that continue to eat into the bond income that pension plans have long relied on to meet, or at least measure, their future obligations.

The so-called discount rate - the proxy that pension plans use as the expected income they will make annually from a corporate bond - is at 4.06 percent, compared with nearly 5 percent two years ago and 6.2 percent at the end of 2008. Pension funds have in the past had to use that discount rate to calculate the net present value of their obligations.

"You've just seen a ballooning effect of liabilities" as the discount rate continues to fall to new lows, said Zorast Wadia, a principal at actuarial firm Milliman.

At the same time, weakness in the U.S. stock market wiped out $83 billion in plan assets in the first two months of this year, widening the overall pension funding deficit to $487 billion, according to Mercer.

"In just two months we have seen the entire improvement in funded status from last year disappear," said Jim Ritchie, a principal in Mercer's retirement business. A recovery in stocks this month will have helped to mitigate the problem.

Of the pension plans operated by S&P 1500 companies, 59 percent are below 80 percent funded, Mercer estimates. In 2007, before the financial crisis, the average corporate pension was 104.3 percent funded, while in 2000 the average pension plan was 121.9 percent funded, according to Mercer data. A few companies such as General Electric Co <GE.N> and General Motors Co <GM.N> have announced plans to increase their pension contributions this year, rather than pay higher premiums to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp, a federal government agency that insures private defined-benefit pension plans.

As of the start of this year, companies that operate their own plans pay a variable-rate premium of $30 per $1,000 of underfunded benefits, up from a rate of $24 in 2015. GE, for instance, expects to contribute $930 million into its plan this fiscal year, while GM expects to contribute $2 billion into its plan. Zion estimates that 48 companies in the S&P 500 - a group including aluminum maker Alcoa Inc <AA.N>, Boeing <BA.N>, and electric utility PG&E Corp <PCG.N> - could see their cost of servicing pensions drop 5 percent and interest costs drop 20 percent under the new SEC rules, resulting in a more than 5 percent increase in their pre-tax income.