One of the enduring insights of modern finance is that investment strategy is far more productive when focused on risk management rather than return. It's also clear from decades of research that the primary risk factor in the money game is the economic cycle. Connecting the dots, it's easy to see that even a small degree of insight into macro's ebb and flow can yield strategic benefits for managing asset allocation.

If you could muster the powers of prediction for just one variable, forecasting recessions and recovery would surely be at the top of the list for dispensing the proverbial silver bullet in money management for the long run. Risk premiums bounce around quite a bit and the No. 1 reason is that the economy cycles between growth and contraction. Turning this simple fact into above-average excess return would be a breeze if the future were clear. Oh well. Uncertainty shuts down that avenue of possibility. Or does it?

No one knows what the months and years ahead will bring, but that's not the same thing as saying that handicapping the future is worthless. In fact, developing perspective about tomorrow and beyond starts with one sturdy detail that's virtually assured: A new recession is waiting in the wings.

Recessions are a persistent lot. There have been 33 since 1857, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the official arbiter of turning points in the U.S. business cycle. It's a safe bet that number 34 is lurking in the future. "I devoutly hope our next downturn won't come for quite some time, but it surely will come eventually," Dallas Federal Reserve President Richard Fisher said in a recent speech.

Exactly what the next cycle brings, and when it arrives, keeps countless economic debates bubbling, of course. But the high confidence that accompanies the forecast that another downturn will arrive eventually is at the core of explaining why returns on risky assets will continue to bounce around.

"The basic theory of finance says that recessions are the fundamental risk that everyone worries about," says John Cochrane, professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. It's also clear that the recurring feature of falling prices during recessions is more than coincidence, he explains.

Macro Intelligence & Missed Opportunities

It's debatable how deeply investment strategy in the real world is conceived with due respect for the business cycle in general, or the outlook for the next recession in particular. What is clear is that minimizing, much less ignoring, macro's role for gaining perspective about expected returns is tantamount to dismissing a fair amount of useful information.

Studying the links between the capital markets and the business cycle isn't new, nor does it offer shortcuts for predicting return and risk. But research in this niche continues to deepen, offering a window of understanding into the crucial framework of asset pricing. Even better, the investment opportunities identified in this corner of finance aren't being arbitraged away quickly, if at all.

Why is so much constructive research about the markets and the economy routinely unexploited? It's common knowledge that fluctuations in risk premiums tend to exhibit what's known as mean reversion over time. High performance leads to the opposite, and something similar applies to the economic cycle. In other words, when you invest is just as important as the design and management of asset allocation. The close association of broad economic trends with excess returns is the reason. But even wide recognition of this link doesn't inspire timely adjustments in asset allocation as a general rule.

A number of studies show that investing habits in managing the asset mix are conspicuous mostly for the lack of action, particularly among individuals. "One of the major drivers of household portfolio allocation seems to be inertia," comments one report ("Do Wealth Fluctuations Generate Time-Varying Risk Aversion? Micro-Evidence on Individuals' Asset Allocation," by Markus. Brunnermeier and Stefan Nagel, in the American Economic Review, June 2008).

That's not the first time that the crowd's lethargic habits have been scrutinized. The Michigan Retirement Research Center at the University of Michigan evaluated nearly 1 million 401(k) investors over a recent eight-year stretch and found that results generally trail a naïve equal-weighted asset allocation strategy ("The Efficiency of Pension Menus and Individual Portfolio Choice in 401(k) Pensions," by Ning Tang, et al). Meanwhile, a 2004 study reveals that nearly half of 16,000 investors with TIAA-CREF retirement accounts made no active changes to their asset allocation for the decade through 1999 ("How do Household Portfolio Shares Vary With Age?" by John Ameriks and Stephen Zeldes).

The widespread habit of inaction reminds us why rebalancing in a timely manner can be so productive for earning above-average returns. "Slow moving capital," as one research paper remarks, is a key factor for explaining the dramatic changes in realized Sharpe ratios (volatility-adjusted risk premiums) in the stock market over time ("Is the Volatility of the Market Price of Risk Due to Intermittent Portfolio Re-balancing?" by YiLi Chien, et al).

What's behind the market's volatility? The details are debatable, but it's clear that the main catalyst is the business cycle. Then again, could it be that the market influences the ebb and flow in the economy? Maybe it's a bit of both.

Empirical Facts

You can't "prove" anything in economics, but there's no shortage of smoking guns to consider for assessing the odds of the next recession. The future is unpredictable, but that's hardly the basis for practical advice unless your time horizon really is measured in decades-and you have the steely discipline to ignore short-term volatility. Otherwise, developing some macro perspective for managing risk is worthwhile. That includes keeping an eye on a number of empirical "facts" uncovered over the years:

The stock market has peaked ahead of seven of the last nine recessions. During the other two downturns, equities topped out in the early stages of the economic contraction via sharp market declines.

Stock market volatility jumped sharply higher just before the onset of eight of the last nine recessions.

The Treasury market yield curve inverted (short rates above long rates) in advance of every recession over the last 40 years.

Stock market volatility has dropped to relatively low levels before recessions, but it spikes upward during the early stages of economic downturns.

The price of crude oil has substantially increased before or during the early stages of every recession since the early 1970s, which marks the start of free-market energy pricing.

Credit spreads are countercyclical: Yield premiums in corporate bonds over Treasurys have widened in advance of approaching recessions in recent decades.

These insights merely scratch the surface of the macro-market connections that have been identified. Useful as they are, there's nothing particularly surprising here. It's widely known that economic risk explains some of the better-known sources of excess return, such as the small-cap and value stock premiums. The celebrated research by professors Eugene Fama and Ken French in the 1990s theorized as much, and plenty of follow-up analysis strengthens that view. For example, one study quantitatively profiles the extent of the link between small-cap and value factors and the business cycle ("Can Book-to-Market, Size and Momentum Be Risk Factors That Predict Economic Growth?" by Jimmy Liew and Maria Vassalou, Journal of Financial Economics, August 2000).

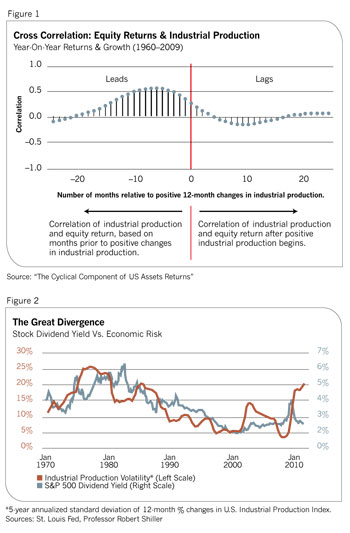

As researchers keep digging, the details on the interaction of markets and macro continue to yield informative results. Consider "The Cyclical Component of U.S. Asset Returns," a working paper in which David Backus and his co-authors outline "the common tendency for excess returns to lead the business cycle." The evidence "suggests a macroeconomic factor in the cyclical behavior of asset returns and the equity premium in particular." The study analyzes the correlation between U.S. equity returns and industrial production over the past 50 years and finds that relatively high equity premiums tend to be followed by stronger growth in industrial production within a year.

The relationship over the past half century is illustrated in Figure 1, which summarizes the correlation profile between annual changes in the equity market and subsequent annual changes in industrial production, a proxy for the broad economy. Note the tendency for correlations to rise ahead of increases in industrial production. The process generally reverses itself after industrial production rises. The basic message: High equity returns imply high economic growth in the near future and vice versa.

A similar relationship holds with yield spreads and industrial production. "Roughly speaking, the evidence suggests that several months before an increase in economic growth, returns on equity rise and the return on the short bond falls," the study advises. "If we put the two together, we see that changes in economic growth are preceded (on average) by an increase in the expected excess return on equity; that is an increase in the equity premium."

What's the economic logic? Backus (a finance professor at New York University and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research) provides one possible scenario. In an interview with Financial Advisor, he explained using an approaching cyclical downturn as the setup.

"You can imagine there being two types of agents in the economy," he said. "You have people who are very risk averse and people who are not so risk averse. If something happens that [diminishes the influence of] the not-so-risk averse people, it's going to be the more risk-averse people who are pricing the assets and the price of risk is going to go up. You can think of that as being a streamlined metaphor for the financial system that suddenly gets squeezed, and so those are the people bearing a lot of risk. Now all of a sudden they bear the risk because they basically run out of money. That means some other sectors of the economy have to bear this risk. That's going to widen spreads. If you feed that into a macro model, all of a sudden people are going to stop investing. Why? Because the cost of financing investment just went up a lot. Investment is inherently risky, and we're going to price that in a way that's a lot less attractive."

It's no secret that markets offer clues about future turning points in the economic cycle, although the flow of intelligence can be thought of as a two-way street to a degree. Forecasting equity returns, for instance, is a function of the current state of the economic cycle, according to "Business Cycle Variation in the Risk-Return Trade-off," a working paper by professors Hanno Lustig and Adrien Verdelhan, both of whom are also NBER researchers. "Average equity excess returns are higher during recessions than during expansions," they write.

Crunching the numbers on more than a half century through 2009, Lustig and Verdelhan show that risk-adjusted equity returns (based on one-year holding periods) generally rise for a period of up to roughly seven months after the economy peaks, based on official NBER cycle dates. The pattern holds in reverse during expansions: Excess returns fall for about half a year once the economy starts growing again in the wake of recessions. Comparable patterns are found in other large economies.

Regime Change

Monitoring the economic cycle and risk premiums simultaneously provides one level of strategic analysis, but some researchers assert that there's another level of macro-market connectivity to consider. The regime, as economists say, matters too.

Fluctuations in risk premiums seem to coexist within longer-term periods of macroeconomic volatility. Risk premiums rise and fall in the short term based on the economic cycle. At the same time, the magnitude of those changes appears to be dependent on the prevailing state of economic risk-the regime.

Reviewing a century of U.S. data, a recent study finds a strong positive correlation between the level of volatility in the nation's gross domestic product (GDP) and the stock market's dividend yield. The connection suggests that shifts in the general level of macroeconomic risk-a regime change-is a factor, perhaps the dominant factor, for changes in the equity risk premium over medium- and long-run horizons. One of the empirical clues: Lower dividend yields tend to coincide with lower economic volatility, and vice versa, according to "The Declining Equity Premium: What Role Does Macroeconomic Risk Play?" (by Martin Lettau, et al, in the Review of Financial Studies, July 2008).

By that standard, the relatively modest level of macro risk over the two decades before 2008-the "Great Moderation"-may explain why the realized equity risk premium for the past decade is unusually low. For the ten years through February 2011, the U.S. stock market's excess return was just over 1% annualized (the total return on the Russell 3000 less three-month Treasury bills). That's far below the long-run average of nearly 6% since 1926, according to Ibbotson Associates.

Does the recent return of sharply higher economic risk imply higher equity returns for the long-run future? Volatility has increased recently, thanks to the Great Recession and the financial crisis of 2008. Using industrial production as a proxy for economic activity shows that macro risk has recently jumped to heights unseen in nearly 20 years.

Why should higher economic volatility be associated with higher expected returns? One explanation: Investors demand additional compensation for enduring more risk. Modern finance theory assumes as much, and there's no shortage of supporting empirical studies. Consider the evidence that economic volatility tends to drive stock market volatility, a relationship found throughout foreign markets, according to "Measuring Financial Asset Return and Volatility Spillovers, With Application to Global Equity Markets" (Francis X. Diebold and Kamil Yilmaz, The Economic Journal, January 2009).

Estimating how the market prices risk in real time is tricky, of course. Among the useful clues is the dividend yield, which boasts a productive history for discounting expected equity returns. That inspires comparing the market yield to economic risk. The relationship is far from perfect, as Figure 2 reminds us. Yet it's also clear that the fall in macro volatility over the years has been accompanied by a lesser dividend yield.

More recently, economic risk and yield have risen sharply. But while macro volatility is still high, the dividend yield has recently tumbled ... again, thanks to sharp gains in stocks since the last recession ended. Will the divergence narrow? If so, under what conditions? Is the recent jump in economic risk a temporary affair that will soon give way to a revival of the Great Moderation? Or will the dividend yield rise (i.e., stock prices fall) in sympathy with a new era of elevated macro risk? It's too soon to say for sure, although the relationship bears watching.

The Problem Is Us

Looking for signals from the evolving relationship between macro and markets isn't easy, but it can be helpful when used with other tools for estimating return and risk. For all the econometric studies to draw on, however, a certain amount of finesse is needed to soften the hard fact that turning points in the business cycle are easier to see after the fact. No wonder that NBER typically waits a year or more to retroactively call peaks and troughs. Finding real-time clues is a challenge, but not necessarily hopeless.

Once again, the financial literature suggests lots of intriguing possibilities. Electricity usage, for instance, is considered a valuable proxy for monitoring the business cycle in real time. It's a practical idea because, a) electricity consumption/generation data is available monthly with minimal lag; and b) electricity can't be stored, which makes it a useful benchmark of real-time demand for economic activity. Accordingly, history suggests that electricity can shed light on expected risk premiums ("Electricity Consumption and Asset Prices," a working paper by Zhi Da and Hayong Yun).

Dissecting the finer points of macro and markets is helpful, but it doesn't automatically make exploiting the apparent opportunities any easier. "One of the hard facts for all of us to chew on is that when prices are low relative to book value, dividends, earnings, etc. doesn't seem to indicate that future earnings are going to be bad," notes Chicago University's Cochrane. "That seems to indicate a buying opportunity: a time when returns are going to be higher."

Yet history also shows that relatively few investors are willing or able to act on this information in a timely manner. Some analysts say that's a sign of irrationality. Perhaps, although the future is always at risk of playing out differently than what history implies. Cochrane recommends taking the contrarian route only if you can afford to take risks that the crowd can't or won't take. "We can't all be smarter than average," he says, "but we can all find a piece of risk that we're more willing to bear than somebody else."

Locating one or more of those pieces isn't necessarily the problem. Financial research has made great strides in identifying those times and conditions when certain slices of risk appear to offer superior (or inferior) return-to-risk ratios. But turning this information into realized risk premiums is still hard, and it always will be. The human mind, it seems, is as much a source of progress in finance as it is an impediment to reaping the rewards. That dual nature is probably the reason the economic cycle is in no danger of extinction and risk premiums will continue to fluctuate dramatically.

James Picerno is a freelance writer and author of Dynamic Asset Allocation.