Traditional pensions are gradually disappearing from American culture. More and more of us will depend on our own investments to cover some or all of our living expenses during our "golden years." Prospective retirees' goals are pretty straightforward: to enjoy a satisfying retirement and to provide a meaningful inheritance for their families.

That dream seemed secure through the '80s and '90s when U.S. investors were enjoying steady double-digit annual returns from both stocks and bonds! But a strange thing happened on the way to retirement ... the world got a lot more dangerous!

You already know that interest rates have become microscopic; so-called "safe" investments like bank accounts and government bonds pay less than the rate of inflation! And, of course, the value of the home that many of us were counting on as a retirement asset has shrunk. Well then, what about stocks, the supposedly highest-return asset class? We've seen stock values cut in half twice in the last 12 years!

Most people who've been looking forward to a happy and secure retirement weren't anticipating these sorts of disappointments! Fear is rising among would-be retirees.

All of which brings us to the subject of this edition of the Blue Sheets: RISK ... specifically, investment risk as it pertains to retirement income security.

Mr. Webster describes RISK as exposure to the possibility of loss or harm.

Very few people actually enjoy risk. But life has taught us that the companion to every decision we make is the possibility that it will not work out as well as we had hoped.

We decide what school to attend, whom we will marry, where we will live, and what sort of work we will do. All of these decisions involve a risk of disappointment or loss; yet we keep making important decisions because, as Melinda Gates said, "We believe in taking risks because that's how you move things along."

And so it is with investing for our retirements. In this edition of The Blue Sheets we will examine with you the various faces of investment risk, and outline the Financial Advantage discipline for managing these risks to a happy outcome.

Risk Needn't Be Scary

When most investors hear the word "risk" they imagine big declines in the market value of their 401(k) or brokerage account. When your account value shrinks month after month, and you're really not sure why, it's easy to imagine that you are just not lucky or that the deck is stacked in favor of the insiders. And a natural instinct is to want out... to stop the pain.

But, for most retirees, trying to avoid risk by not investing is a terrible decision. It's a decision to give up on your dreams. When you come to understand that all the different kinds of investment risks which we will describe have been irritating investors throughout the history of free market capitalism, you will begin to see that risk is just a reality that needs to be managed.

Farmers learn to cope with dramatic weather changes. Retailers must adjust to radical changes in fashion. Aerospace engineers are continually pushing the frontiers of materials strength. Yet, despite inevitable setbacks, all these professionals keep achieving wonderful successes.

And so it is with investment managers. Our professional challenge is managing perpetual uncertainty. When we make decisions to invest in a company's stock, there is a chance that its leading product might be broadsided by a new invention. If we buy a government bond, we do not expect that country's credit to be suddenly downgraded... but it could. If we invest money in a mutual fund, we are making a commitment to a certain manager's investment style... which could always go out of favor.

In each case we are acting on a particular conviction about the future ... about a company's likely success in its market ... about the growth of consumer spending ... about a nation's currency and its fiscal policy ... about a business sector's growth prospects ... or about the valuation of stocks in general. But the future is always unknown. Always! In a global economy as dynamic and multi-faceted as ours, there will be constant surprises, some good and some not so good.

Because the risk of disappointment is ever-present, we believe long-term investment success requires:

a) Emphasizing highest convictions about the future, derived from continual research

b) Making diversification an unwavering commitment

c) Focusing on fundamental value; not overpaying

d) Being adaptable when the future unfolds differently than expected

Different Kinds Of Investment Risk

At FAI we find it helpful to sort investment risks into five distinct categories. Each has unique characteristics. And they tend to be more or less threatening in different economic environments.

Fortunately, not all investment risks are prominent at the same time, so our defensive emphasis needs to shift over time depending on which kind of risk is ascendant. And, sometimes the market fully recognizes a risk by discounting the prices of securities that are most exposed to it; in such cases, a risk can actually become an investment opportunity!

Here is a brief description of the five kinds of risk. We will elaborate later and describe our portfolio disciplines for managing each variety of risk.

1) INFLATION RISK, i.e. the probability that the currency in which we measure our incomes, debts and assets will lose value (buying power) over time. Persistent inflation is a compelling motivation for even risk-averse savers to expose at least part of their nest egg to price risk in the expectation of realizing inflation beating returns over time.

2) ISSUER RISK. There is always some possibility that a government or company which issued bonds might not make interest or principal payments as promised; or that a business in which you own shares might fall on hard times. In either case, a price decline would be a normal consequence of the issuer's changed condition.

3) VALUATION RISK or "Market Risk." Separate from the health of individual issuers of securities, there are seasons and cycles in the markets themselves that influence the valuation of securities. A business may be doing "just fine, thank you," yet for months or even years the price of its stock could fall due to market factors unrelated to its business. Market valuations of both stocks and of bonds tend to run in long cycles, presenting, alternately, risk and opportunity for investors.

4) MACRO-ECONOMIC RISK. Economic activity in free markets tends to expand gradually over time due to population growth and rising workforce productivity that comes from innovation. In general, economic growth is a long-term positive for stock prices... but growth is cyclical and surprisingly erratic. Even a temporary contraction in spending by consumers, businesses or governments can depress corporate profits and stifle investor enthusiasm for stocks. A rising or falling trend in interest rates also has a strong influence on both bond and stock prices, as do demographic changes, savings rates, shifts in competitiveness among nations, and the direction of regulations and other government policies.

5) SYSTEMIC RISK. The development of paper currencies and fractional-reserve banking, and the evolution of liquid public markets in all sorts of securities have made possible the integrated global economy we now take for granted. A rupture to this complex and somewhat fragile financial system, say from liquidity or solvency crises, electronic terrorism, social upheavals or wars, could provoke wide-ranging economic turmoil. We believe risk to the system is not trivial. More later.

Investment Risk Is Unavoidable For Most Of Us

The risk management profession teaches that there are four basic strategies for handling risks once they are identified: avoiding them, transferring them to another (insurance), minimizing the potential consequences, and accepting the risk while budgeting for the consequences.

Those of us who expect to cover our retirement expenses from our life's savings really don't have the first option, avoidance, because not only does all investing include some element of risk, even not investing includes the on-going risk of currency debasement (Inflation).

At age 65, Bill and Marylou Daily's situation is typical of upper middle class retirees. Their comfortable home is paid for. They can't qualify for long-term care insurance, so nursing care is a meaningful unknown. Their adult children have very little savings, so they'd really like to give them a boost in life with some inheritance. In today's dollars, Bill and Marylou project that for living expenses and income taxes they'll need $50,000 a year above what they'll receive from Social Security. They have just retired with $1.5 million of investment assets.

If we assume future inflation of 3.4% (the long-term U.S. average) it seems these people will need a nominal investment return averaging about 7% a year to achieve their goals. Currently, ten-year U.S. Treasury bonds pay just 1.5%, and one-year bank CDs offer barely 1.0%. Clearly, Bill and Marylou's portfolio strategy needs to include some investment risk if they are going to have any chance of realizing their goals.

Let's examine the five kinds of investment risk, one by one, and outline our FAI strategies for managing each one in an investment portfolio.

INFLATION RISK

For those of us who live and work in the United States, the value of everything is denominated in U.S. dollars. Some examples: An executive may earn $150,000 a year. Her portfolio is worth $1,700,000. A certain house just sold for $660,000; its property tax is $8,500 a year. A new Honda Pilot costs $42,000. One family's living expenses are about $120,000 a year.

The thing is, if we made this same list 10 years ago or 10 years from now, most of the numbers would be significantly different. We might expect the dollar cost of some things to decline because we live in a free market economy where innovation brings efficiencies to our manufacturing and distribution processes. But a relentless upward pressure on prices is government's purposeful increase in the amount of dollars in circulation relative to the level of economic activity in the country.

Controlling the supply of dollars was assigned to the Federal Reserve System in 1913; the Fed is charged with maintaining stable prices and a vibrant economy. In the 99 years of the Fed's existence, based on the government-maintained Consumer Price Index (CPI), the buying power of a dollar has shrunk by 3.23% per year.

That means that the current buying power of a 1913-dollar is only 4.3 cents! Said another way, a basket of consumer goods and services that cost $100 when the Fed first came into existence would cost $2,300 today because of the gradual erosion of the purchasing power of the dollar! This is why we believe retirees need a game plan for offsetting inflation with investment gains.

In the four most recent calendar years, CPI inflation has averaged just 1.8% a year in the United States. Some commentators have suggested that this indicates a reduction of the long-term inflation risk. We do not share that opinion. As a matter of fact, we think that longer-term inflation risk (the debasement of paper currencies throughout the world) has increased since the 2008-09 "credit crisis" because central banks around the world have dramatically expanded the money supply in a misguided and failed effort to "stimulate" economic activity.

What central banks have done is facilitate an unprecedented increase in the burden of sovereign debt on the private economy, thus increasing governments' motivation to devise inflationary monetary policies around the world.

The speed at which available dollars circulate through the system (velocity) has dropped to historic lows since the residential real estate bust; this has muffled the impact of loose monetary policies on the general level of prices. When velocity begins to revert to its historic mean, as most financial data series eventually do, we believe inflation will move higher. This is surely the will and intent of the powers that be.

But it's important to note that the modern credit boom could end, instead, in widespread defaults and a massive credit contraction. If that should be our lot, the world would probably experience deflation (falling price levels), not inflation. Our position is that a wave of modest deflation could surface temporarily in a recession as excess inventories clear ... but that political forces are clearly arrayed on the side of inflation; the ultimate risk here, of course, is that their efforts get out of hand and produce hyperinflation. This is a very serious investment issue; to remain watchful and adaptable will be critical ... for businesses and for investors.

FAI Discipline For Managing Inflation Risk

1) Invest in businesses with above-average pricing power due to competitive advantages and/or because their products or services are essential. (Adaptive companies should also be able to cope with deflation if that develops.)

2) Invest in "Hard Assets" that tend to rise in price during periods of rising inflation. Our positions include gold bullion and gold mining, energy pipelines, timberland and politically-secure oil and gas reserves.

3) In our fixed-income portfolios:

a) Emphasize shorter maturities that can roll into higher-yielding replacements as interest rates rise

b) Make use of adjustable rate securities such as TIPS and Bank Loans

ISSUER RISK

From time to time, any company can become the subject of news, opinion or rumors that might influence the market value of its securities, for good or for ill. A headline could be about the company itself, about an aspect of the economy that affects its business outlook, about developments at a competitor, and so forth.

Being a shareholder in any publicly-owned company includes the possibility that the market value of the investment might be impaired by such information; sometimes it's a temporary influence, sometimes the implications are longer-term in nature.

This issuer-specific risk is separate and distinct from general market valuation risk that may affect whole asset classes.

FAI Discipline for managing Issuer Risk

1) Intensive, ongoing research regarding each issuer's competitive position, balance sheet and business risks

2) Limiting the size of individual positions, and diversifying across a large enough number of issuers to limit the potential risk from any single investment

3) Screening for overlypessimistic or overly-optimistic consensus expectations regarding an issuer... i.e. surprise potential.

VALUATION RISK

Historically, stocks as an asset class have provided a much higher return than bonds... 9.2% a year since 1927 versus 5.1% a year for bonds. To put those two numbers in some perspective, a 9.2% compound return will double an investment in 8 years. At 5.1% that would take 14 years.

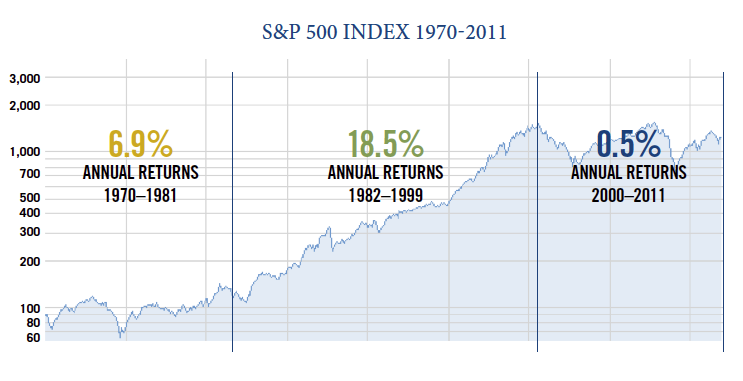

But stocks have an offsetting unattractive feature... their investment returns have been very, very volatile. Just since January 2000, for instance, the S&P index of 500 large US companies has experienced two periods during which the average stock price collapsed by about 50%! The reward to shareholders who endured all that anxiety has been a whopping 1/2% annual return!

In the above chart of the S&P 500 stock index since 1970, two things jump off the page:

1. The amazing run-up from 1982 to 1999 (18.5% annual returns)

2. The gut-wrenching roller coaster rides in the 12 years before that blessed era (6.9% annual return) and in the 12 years since (0.5% annual return)

From Jan. '82 until Dec. '99, the S&P index value multiplied more than 12-fold! When we include dividend payments, returns were 18.5% a year, compounding for nearly 18 years!

What is seldom pointed out about this charmed era of financial history is that corporate earnings in the same period rose just 8.2% a year (4.9% a year if we adjust for inflation). So, what made stocks perform so much better than the businesses they represent? VALUATION; the P/E for the index marched from 7X to 34X. And that, as they say, made

all the difference.

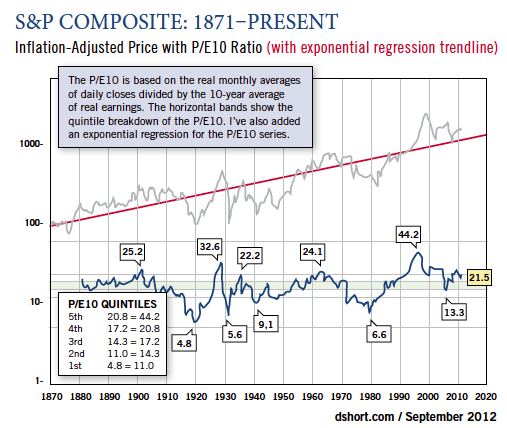

(See the P/E graphic on the above chart from dshort.com; note the definition of P/E in the box. By averaging the latest 10 years' earnings it smooths the valuation distortions of single-year P/E volatility. The upper and lower ranges are especially instructive.)

History's valuable lesson is that price risk rises as valuation rises. That's not all you need to know, by any means; for example, high valuations in the 1960s and early 1990s were followed by years of market strength. Still, attention to this principle can spare an investor a lot of grief. The bursting of the "dotcom" valuation bubble in 2000-2002 is a classic example.

Our discipline for enhancing long-term returns and limiting volatility is to trim equity exposure during periods of above-average valuations, and to increase exposure when valuations are more modest. Our preferred valuation metric is the Shiller PE-10 which measures price against a 10-year average for S&P earnings to smooth for cyclical earnings extremes which often distort the traditional 12-month P/E ratio.

FAI Discipline For Managing Valuation Risk

1) We maintain several proprietary Risk Profiles to accommodate individual clients' different tolerance for price volatility. Each profile is assigned a different equity exposure range.

2) We monitor and adjust our actual equity allocation within each profile's range based on the attractiveness of the current P/E-10 for the S&P 500 in historic context.

3) In selecting individual stocks, we weigh each company's current stock price against our future earnings expectations for that firm, and compare it to the overall market P/E.

4) When we identify whole business sectors or groups of securities that appear undervalued relative to the larger equity market, we search there for investment candidates.

5) When stocks and bonds are both expensive, markets attract traders and tend to be volatile; this presents short-term opportunities, which we address by using outside managers with documented success in tactical disciplines.

MACRO-ECONOMIC RISK

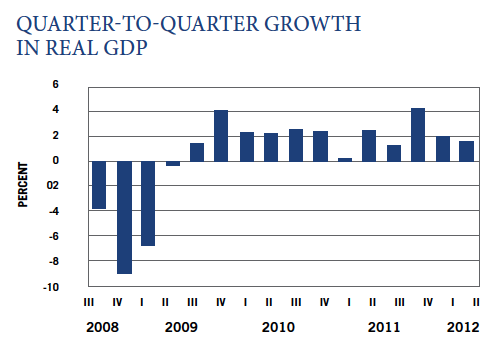

Every company's business is to some extent influenced by the economic environment in which it operates. During a recession, an electric utility expects the demand for its output to shrink; during an expansion, to grow. When consumer confidence is high and employment is rising, retailers expand their inventories to take advantage of the opportunity. These are routine business-cycle sorts of issues. Over the years it has been our experience that trying to invest by anticipating recessions and recoveries is not especially fruitful. It's a Wall Street adage that "economists have forecast 9 of the last 3 recessions!"

What seems to us a much more practical and rewarding approach is to rise a bit higher above the cyclical fray to study the economic inputs that drive growth over the longer term. We will be writing more extensively about this in the future, but here is a short-hand summary of an important change that we think is underway in the world... change that

will impact investment risks and opportunities in a number of ways.

Not to keep you in suspense, here follows our rather sober take on global economic growth prospects for the next 5 years. Real inflation-adjusted economic growth in post WWII America has been on the order of 3.0% to 3.5% a year. Before the recent financial crisis, GDP made only 3 brief, shallow excursions into negative territory in 30 years. No doubt, the consistency of growth boosted investor confidence and gave us the unprecedented valuation explosion

of the '80s and '90s.

even further based on the reality that our own Federal government continues to spend about 50% more than its annual tax revenue, driving U.S. national debt higher by 8% to 9% each year! And heaven help us when we have to start rolling over short-term Treasury debt at un-manipulated market interest rates.

Nor is demography encouraging: population growth has shrunk to less than 1% a year, a 27% drop since 2000. And our workforce has dwindled from 67.3% of adults to just 63.6%. During our 3 - 3.5% GDP growth years, the workforce participation was increasing; it has been shrinking for a decade and more shrinkage is likely as Boomers retire at a faster clip.

We believe that real US economic growth over the next five to 10 years will very likely be a shadow of the growth that markets treated as a birthright in the past 50 years. The main culprits are:

A high and growing debt burden on consumers and on government at all levels

The probability that interest costs will grow even faster than the debt

Rising income tax rates and means-testing of benefits

The aging of a population which is ill-prepared for retirement

Tepid prospects for improving our trade deficit with the rest of the world

FAI Discipline For Managing Macro-economic Risk

1) We invest in the most competitive and financially robust companies we can find because we believe they can grow even in a slow and halting economy by gaining market share from weaker competitors.

2) We avoid broad stock indexes because they include less competitive companies; indexes were a convenient way to diversify when a rising economic tide was lifting all barges.

3) We think slower growth will produce lower peaks in the valuation range; so, we reinterpret the historic P/E-10 range

to make it a more appropriate guide for our equity allocation.

4) We are giving increasing emphasis to dividends; in a slow growth economy, many companies can reduce capital spending in favor of greater shareholder distributions.

5) Some emerging markets still have better demographics, stronger finances, competitive labor costs and lower corporate tax rates than the U.S.; though we are watchful on the issues of freedom and export dependence, the EMs currently have a meaningful place in our portfolios.

6) Although some of the U.S. companies we are invested in have significant revenue from Europe, we try to minimize our investment exposure to Europe and the Middle East, as those environments are less hospitable to private capital.

SYSTEMIC RISK

Democratic free-market capitalism is the only economic arrangement in history to have ever delivered the masses from grinding poverty. And yet, despite its extraordinary success, it appears to be losing ground to an alternative vision. The rapidly expanding role of government in the allocation of capital (i.e. the private savings of its citizens) would certainly

alarm French historian Alexis de Tocqueville, who warned famously that,

"Democracy can only exist until the voters discover that they can vote themselves largesse from the public treasury. Democracy always collapses over loose fiscal policy, always followed by a dictatorship."

(Democracy in America, 1835)

With America's national debt suddenly surpassing her annual output of goods and services, and with our federal spending exceeding the tax revenue by some 50%, "loose" does seem an appropriate description of our country's fisc.

Milton Friedman (1912-2006) was perhaps the most effective champion of democratic free-market capitalism since Adam Smith (1723-1790).

Stephen Moore, senior economics writer for the Wall Street Journal, wrote a tribute to the man this year on the anniversary of his birth. Moore recalled a dinner conversation with Friedman in 2005. He asked, "Milton, what can we do to make America more prosperous?" "Three things" the economist replied instantly. "Promote free trade, school choice for all children, and cut government spending."

"How much should we cut?" Friedman's unhesitant response: "As much as possible!"

Well, it seems the political class has not shown much enthusiasm for cutting government spending to unleash the energies of the private sector. As things have turned out, in the six years from 2006 through 2012, nominal GDP expanded by 16% while federal spending exploded by 43%! It is clear what part of the economy has been "stimulated"

by deficit spending.

Since tax revenue from a moribund private economy has been flat in recent years, the annual federal deficit is now running at a stunning 8.5% of GDP. Total debt has doubled in the last six years to more than 100% of GDP, and it will grow and grow unless the electorate shows more economic wisdom than de Tocqueville supposed they might. Growth of government debt above its current level poses a serious risk to our free-enterprise system.

Veteran columnist Daniel Henninger recently opined that America now consists of two separate economies... not haves and have-nots, but government and private. And they are, he contends, competing for dominance. Total government spending (federal, state and local) tallies a formidable 40% of GDP this year!

How great is the risk to the most productive economy in history? Judging from interest rates, equity valuations and estimates of earnings 12 months out, the market's opinion appears to be that the risk is manageable. Securities prices do not seem to be discounting any likelihood that debt and politicization of the economy will diminish its vigor longer term.

For the last five years, the annual federal deficit has been running at TRIPLE the level of personal savings in this country! That's $1.2 trillion being consciously withdrawn from the private capital stock every year! Squadrons of elected officials have struggled to propose a way to close this economic vortex; but any real solution has to include long-term fiscal discipline, something that is apparently inconsistent with the need to run for office every 2 to 4 years.

The track record of democratic, free-market capitalism in delivering a rising standard of living for ordinary people is so superior to anything else that has ever been tried, that we are very confident it will eventually be restored to health; that the symptoms, while frightening, will not be terminal.

That's the good news. The more disconcerting news is that if the electorate refuses to choose political leaders who will speak the truth to us about the limitations of government and about the seriousness of our situation, then the proper balance will eventually be restored by a global financial crisis rather than by sober fiscal and monetary policies.

This is an election year, and a healthy policy change is still possible. But if we the people reject an opportunity to recover financial propriety, then we'll get what every spendthrift deserves.

Hundreds of prosperous, hard-working families trust us to keep their life savings both safe and productive... in good times and bad. Their hopes and dreams are the reason that we remain vigilant concerning the systemic risks to the country's savers.

FAI Discipline For Managing Systemic Risk

The risk-management strategies we have described in this issue are premised on the assumption that America's work ethic and spirit of innovation will continue to attract capital from all over the world, that capital will demand and eventually receive a reasonable return, and that only the private sector can deliver that return.

Our portfolio allocations in both stocks and bonds reflect our blend of near-term caution and longerterm optimism:

1) Our allocations are global, because the new reality is that nations with billions of citizens are moving clumsily toward the economic model that America has showcased for 200 years.

2) Our portfolios have a distinctly American "tilt" because we think this country still sets the standard for democratic free-market capitalism.

3) Our stock allocations are smaller than they would otherwise be to allow for potential economic disruptions related to the systemic debt burden; a purgative financial crisis could put the best companies in the world on sale and we want to be ready!

4) Our equity investments are, as always, selected based on their underlying business value, and, especially in our domestic portfolio, they reflect our preference for businesses with a history of growing by successful innovation.

The recent explosion in the size and intrusiveness of government has investment implications, including slower overall economic growth and an elevated risk of rising inflation and higher interest rates. Because the knee-jerk governmental response to economic stagnation in the more developed countries has been to "print" money, which eventually debases a nation's currency, two other aspects of our discipline for managing systemic risk are:

5) We are keeping the average maturity of our bond portfolio unusually short; we'll be happy to own longer-term bonds when they offer appropriate real interest rates.

6) As we have for more than 6 years, we maintain a substantial allocation to gold bullion, which we treat as the only currency in the world the supply of which is outside government's immediate control.

CONCLUSIONS

In investing, as in life, tomorrow is forever shrouded in uncertainty.

A child tends to rush ahead impulsively, oblivious to potential dangers. But a responsible adult is more inclined to imagine and compare possible outcomes before taking action, to weigh his willingness to sustain a disappointing outcome, to check her instincts and then make a decision.

Whether we are talking about humanity in general or political and economic actors specifically, the range of completely new futures that we are capable of creating is immeasurable... assuring that few of our current expectations will be really prescient. And so, we learn caution mixed with humility and wonder! Which party will prevail in the elections this year, and how much difference will it make? Can China keep growing at 9% even as evidence of political oppression mounts? Will the Euro survive another year? Two years? Can America manage her immigration issues without disrupting the public weal? Will the Middle East destroy itself, export its hostilities or finally work out some sort of co-existence? What will eventually stop the sovereign debt explosion that we rightly call "unsustainable"?

In a few minutes, you could easily add ten more significant uncertainties about the world that we live in and invest in, and your chances of correctly guessing all the outcomes would be slim to none. But the important lesson is that risk and uncertainty needn't prevent us from fully participating in life. It sure didn't keep the colonists from enshrining the American Dream in the Constitution.

In the world of free market capitalism into which we were privileged to be born, putting our savings to work to support us beyond our years in the workforce is just one of the things we need to do.

As my energetic, Lebanese-born wife likes to say, "YALLA!" ("Let's Do it!"

J. Michael Martin, CFP, is president and chief investment officer of Financial Advantage Inc., in Columbia, Md. This article is reprinted from his newsletter The Blue Sheets.