Wages can also be influenced by the slack in the overall economy, measured in this case by the output gap, the difference between actual gross domestic product (GDP) and potential GDP [Figure 2]. An output gap below zero suggests that there is slack in the economy. When the output gap is negative — and moving further in that direction as it was between the start of the Great Recession and June 2009 — it puts tremendous downward pressure on wages. When the output gap is negative but improving, as it has been since mid-2009, the downward pressure on wages abates somewhat, and that is what we have seen in the wage data to date. In the period just prior to the start of the Great Recession in late 2007, wages were running at well over 4% on a year-over-year basis. By September 2012, after the economy had run below its long-term potential growth rate for more than five years, wage growth compressed to just 1.2%. A pickup the labor market and the overall economy since late 2012 has helped to narrow the output gap and driven wage growth into the 2 – 2.5% range, a big improvement, but still well below the pace seen prior to the Great Recession in the mid-2000s. It’s clear that the Fed, or at least Yellen, wants to see wages move closer to that 4.0% level before raising rates again.

Wages In The Good Old American Know-Hows Sectors Leading The Way

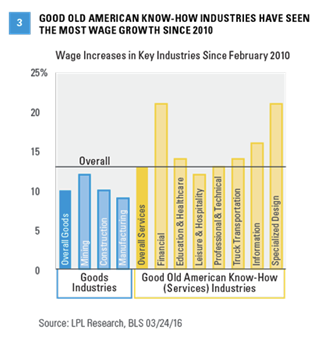

Figure 3 looks at the wage gains seen in the overall economy and in key industries since the labor market bottomed out in February 2010. Overall, average hourly earnings in the private industry have increased by 13% since the economy began regularly creating jobs in February 2010, eight months after the end of the Great Recession. Wages in the broad goods-producing sectors (mining, construction, and manufacturing) have increased by 10% over that span, with mining (+12%) far outstripping construction (+10%) and manufacturing (+9%), despite the collapse in oil prices over the past two years or so. On the services side, wages in the private sector (up 13% since February 2010) have outpaced wages in the goods-producing sector as a whole (+10%). Within the private services sector, one clear winner is the broad financial services area, where wages have increased more than 21% since February 2010 — albeit from a depressed base, as no sector suffered more than financial services during the housing-induced Great Recession. “Specialized design services,” also up 21%, has been another leader in wage growth. Both categories fall under our “good old American know-how” umbrella, including real estate and credit intermediation, commonly known as commercial banking. Wages in those areas are up 17% and 16%, respectively, since February 2010.

Several other good old American know-how segments of the economy, including education and healthcare, leisure and hospitality, professional and technical services, truck transportation, and information services, have seen wages increase more than average since the labor market bottomed out in early 2010, as noted in Figure 3. On balance, while wage growth has been rather tepid over the last 12 months (+2.2%) and since the economy began creating jobs in February 2010 (13% or 2% per year), there is evidence, in our view, that shortages of skilled workers in key areas of the economy have led to a pickup in wages. In addition to hitting that 4% level for wages as noted above, it appears that Yellen and her FOMC colleagues want to see more evidence that those improvements have spread to all sectors of the labor market before moving rates higher again.

John Canally is chief economic strategist for LPL Financial.