Negative Interest Rates: Powerful out-of-the-box thinking or insanity?

By Wendy W. Stojadinovic, CFA

Yes, it’s true: there actually are investors who are buying bonds that have negative yields. For example, investors are buying German two-year government bonds with a 0% coupon for a price of $101 knowing they will only get $100 back at maturity. Or in other words, these investors are paying the German government to hold their money!

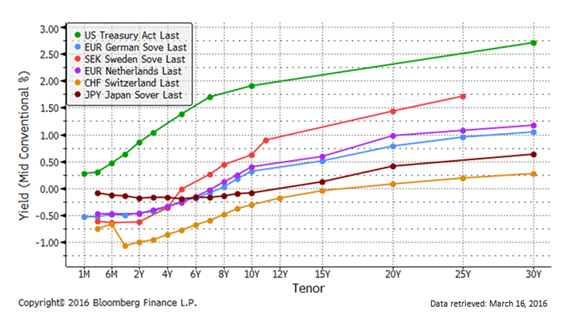

For years I’ve listened to complaints that U.S. interest rates are too low, but when you compare U.S. rates to Germany, Sweden, Netherlands, Switzerland and Japan, U.S. rates are relatively attractive. In these five developed countries, their bonds maturing in five years or less are trading at negative rates. In Switzerland, bonds as long as 15 years to maturity are trading at negative interest rates. According to Bloomberg, more than $7 trillion of global government bonds yield less than zero. This sounds insane; so, why is this happening?

It begins with central bank policy attempting to foster higher growth and 2% inflation. When a central bank sets policy rates, it basically sets two rates: first is the interest rate it will pay member banks for deposits of excess reserves and second is the interest rate it will charge member banks for lending cash to them. In theory, a bank should be highly incented to make loans or other investments that earn it more than what it costs to borrow the money.

In turn, lower bank borrowing costs allow it to lend at lower rates, which should spur demand for loans and lead to higher growth and inflation. Central banks have kept rates at near 0% for years, but there has not been a lot of loan growth. If only it were that simple. There just hasn’t been enough demand for loans due to economic uncertainty, and where there is demand, there are regulatory hurdles that hinder the banks’ ability to make the loans.

Central bank policy rates have enormous influence on the level of short term bond rates, but they have less effect on longer term rates. To increase loan demand, central banks needed to more directly influence longer term rates lower so they implemented quantitative easing (QE). QE occurs when central banks actively buy securities on the open market. The larger the quantity they buy, the more yields on those securities decline. Lower rates also push investors looking for income to take more risk by moving into longer maturities or into bonds with more credit risk in order to get yield. The higher the demand for these securities, the lower those rates go, too, which should also lead to higher corporate borrowing to fund capital expenditures and greater home mortgage demand, which spurs economic growth and inflation.

The U.S. was the first to implement QE, but it stopped QE in 2014 and now other central banks are ramping up. Unfortunately, the central banks of the five developed countries in the chart have had to be even more aggressive with monetary policy by instituting negative rates. To implement the negative rate policy, central banks simply charge (instead of paying) its member banks interest on the cash they deposit at the central bank that exceeds their minimum required balance. If the prospect of earning nothing on excess reserves was not enough incentive to make loans, certainly paying the central bank to hold the cash should be!

Besides stimulating loan growth, negative rate policies have also been used to fight currency appreciation and deflation. To understand the battle of currency appreciation, it’s important to review the theory of interest rate parity. This theory says that the relationship between the currency exchange rates among countries is a function of the level of their local interest rates, such that the variance between each country’s interest rates is about the same as the difference in their currencies. If there is a difference, traders typically come in and arbitrage the difference away. In theory, the value of a country’s currency should rise and fall as its interest rates rise and fall. Therefore, lower central bank rates should lead to a weaker currency which should boost economic activity through exports because that country’s goods and services are now cheaper for foreigners to buy.

With all the intervention by central banks globally to reduce interest rates the last few years, we’ve witnessed a lot more currency volatility. Safe-haven currencies strengthened while currencies in countries where central banks were cutting rates weakened. Sweden and Denmark are known for their safe-haven, stable currencies but too much money flowing in pushes the currencies so high it stifles their ability to export and slows their economies. The Swedish and Danish central banks were the first to impose negative deposit rates in order to reduce capital inflows from other countries and prevent rapid currency appreciation. The Swiss National Bank followed with negative rates shortly thereafter. The Swiss had maintained a cap in the value of the Swiss franc relative to the Euro, but there was so much pressure on the Swiss franc to appreciate that they had to abandon it.