In yesterday’s post, we discussed how the common perception of the oil price decline is significantly out of line with reality. It is just this kind of mismatch that has, historically, created opportunities. Another mismatch situation—with the dollar—offers similar potential.

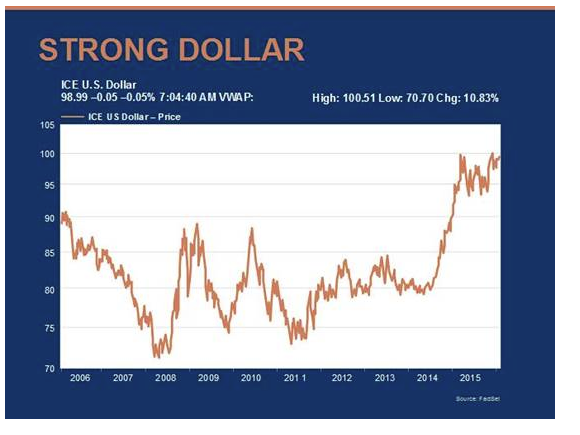

How much higher can the dollar go?

Looking at the past five years, it seems clear that the dollar is at all-time highs and may be headed higher.

It’s easy to see why U.S. companies are struggling to compete in international markets and why profits from foreign sales are down so much. Over time, it is not at all apparent that we will see the dollar decline.

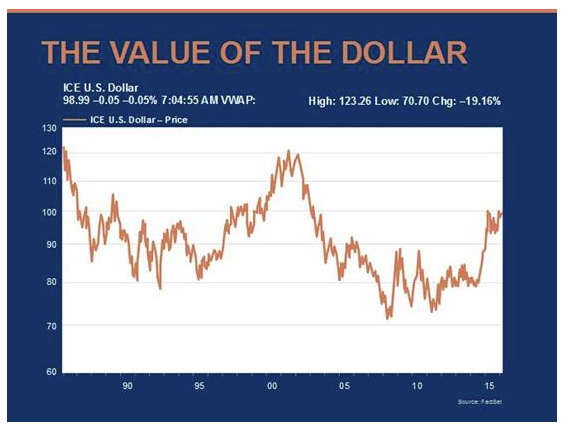

Using a longer time period, however—in this case, 30 years as opposed to 5—we can see that current valuations are actually quite high.

We last saw these values around 12 years ago, in the aftermath of the 2000 financial crisis. Before that, we saw similar values following the 1987 crash and the 1998 Asian financial crisis. In other words, dollar strength, just like oil declines, tends to come after economic weakness and financial crisis, not before it, but most of the time the dollar has been less expensive than it is now.

The influence of interest rates

Historically, and consistently, dollar strength also tends to come from increases in U.S. interest rates, not on an absolute basis but on a relative basis. When other countries are weak, they tend to cut rates more than the U.S. does, and this divergence in policy drives the dollar’s move up or down. Again, this is consistent with the more proactive approach the U.S. takes to a crisis; we typically respond more quickly than other areas of the world and, as a result, recover more quickly.

This is exactly what we have seen in this cycle as well. U.S. rates were cut, both directly and through quantitative easing, well before the rest of the world after the financial crisis, and you can see the dollar decline—to all-time lows—over that time period. In recent months, as the U.S. ended its quantitative easing program and even started to raise rates, and as other countries started to ease, the gap between policies collapsed and then reversed—and pretty much all of that dollar decline disappeared.

Think about what this means going forward:

Will other countries continue to expand their stimulus programs as much as they have in the past year over the next year?

Will the U.S. tighten as much as markets expect?

In other words, is the market properly pricing the likely policy divergence?

Historically, the answer has been no. The dollar’s value tends to decline after the Fed starts to raise rates, for just that reason: the policy divergence tends to revert to normal. This time looks like it may well be the same. Fed tightening was always going to be gradual, and it now seems likely to be even more so. Meanwhile, the ability of foreign central banks to provide additional stimulus is running out.

In other words, the spike after the crisis tends to subside, as we are seeing right now. We may be reverting back to the lower values that have been typical over the past 30 years.

How to take advantage of a potentially weakening dollar?

I have a few thoughts:

A weakening dollar would reverse the damage done to U.S. companies’ foreign earnings, which could have a major effect. Companies that do most of their business outside the U.S. could benefit substantially.

A weakening dollar would also help push commodity prices, including oil, back up in dollar terms. This could be another tailwind for the oil price, on top of the factors I mentioned yesterday.

In both cases, the U.S. is likely to become more competitive, giving a boost to the manufacturing sector, which is more export-oriented than the service sector.

This is, in many respects, a mean reversion argument. The key to using mean reversion successfully is to understand the logic driving the reversion, rather than just assuming it has to happen. Here, that logic is clear and represents a potential opportunity to buy into some beaten-down sectors of the market.

Brad McMillan is the chief investment officer at Commonwealth Financial Network, the nation’s largest privately held independent broker/dealer-RIA. He is the primary spokesperson for Commonwealth’s investment divisions. This post originally appeared on The Independent Market Observer, a daily blog authored by Brad McMillan.