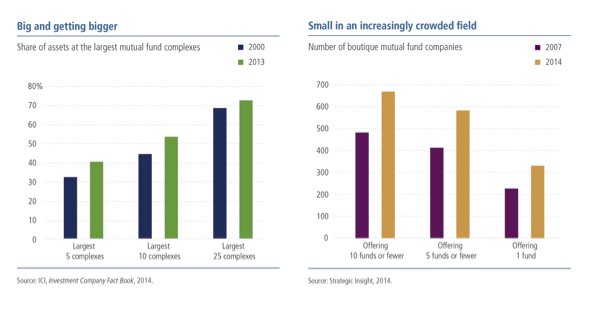

Financial advisors bear an important responsibility when recommending investments for clients, especially in an era of monetary policy experiments, choppy markets and fund manager turnover. Apart from the ever-present fiduciary risks are the business risks of endorsing strategies that produce unwelcome surprises. While fund due diligence based on performance alone is inadequate, qualitative evaluations are difficult without direct access to portfolio teams. Moreover, the universe of high-quality investment managers has bifurcated over time, with large, multi-asset fund companies clustered on one end of the spectrum and small, specialized boutiques on the other. The question for advisors is how best to choose the right managers.

Behemoth Or Boutique?

Many big, traditional, diversified money managers have developed the infrastructure, procedures and support systems to manage styles across multiple asset categories. While commanding a hefty share of the market, these complexes generally employ large staffs of in-house portfolio managers and researchers and enjoy the competitive advantages that scale brings to securities trading and product pricing.

Still, bigger is not necessarily better. The same organizational efficiencies that can drive profits for the largest fund complexes can also stifle innovation and agility. A 2010 study on management structure at investment firms suggests a strong link between hierarchy and herding, the tendency of portfolio managers to follow the trading behavior of their colleagues. Firms with vertical structures, where house views are mandated from the top down (CEO to CIO to asset class team leaders, etc.), can impair a manager’s discretion and sense of empowerment, weakening the incentive to cultivate original insight and leading to overdiversified, market-mimicking portfolios. When all of an asset manager’s portfolio teams rely on the same central research group, one may also question whether a team can maintain an independent perspective.

Advisors face a countervailing model adopted by boutique managers employing specialized investment approaches. Whether they are spinoffs from larger players or entrepreneurial outfits with roots in the hedge fund world, the population of boutiques offering mutual funds has exploded in recent years. In some cases, the investment professionals that founded these firms continue to own and operate them. By offering an ownership stake in the business, privately held boutiques are able to attract some of the best investment talent in the industry while also ensuring that management’s interests are aligned with those of its clients. These firms tend to manage a relatively limited number of strategies and abide by focused investment processes, often developed by founding members. The size and simplicity of their organizations help specialist boutique investment managers respond quickly to changing markets, new opportunities and imminent risks.

Yet not all fund managers are created equal, and few financial advisors are staffed to research and vet the staggering number of boutique managers in the marketplace today. Indeed, the organizational leanness that makes boutiques such nimble investors is precisely what makes them so difficult for intermediaries to embrace. Niche asset managers generally have little in the way of wholesaling forces, marketing departments and product management teams to help explain the process and philosophy of their funds to financial advisors. In fact, many lack the staffing and systems infrastructure needed to produce the kind of reporting that has become industry standard.

Creating A Blueprint For Performance

Whether we are hiring a portfolio team from a large firm or a small one, we’ve found that establishing a clear definition of success is crucial to engaging new investment talent and allowing it to flourish over time. In selecting managers, our goal is not simply to hire the top performer within a particular asset class. Instead, we outline an appropriate set of characteristics we call a performance blueprint -- an objective, measurable template for the patterns of risk and return that we expect from a fund through different market conditions.

A key part of building that performance blueprint is isolating the attributes that matter most. For example, when we analyze an investment manager’s performance, we look at the underlying factors that have driven those returns. We also examine how a portfolio’s composition has changed over time, and how the manager’s allocation decisions have affected performance. This kind of attribution analysis helps us gain deeper insight into the strengths and weaknesses of a particular manager, which, in turn, helps us understand what’s driving the results.

However, past performance, no matter how rigorously it’s evaluated, is no guarantee of future returns, and relying too heavily on historical data can cause one to overlook skilled managers. Similarly, if we rush to replace managers for weak short-term performance, there is a good chance we will miss some long-term winners. We are likely to stick with investment managers when they have periods of weak performance if we understand why. However, we have replaced managers whose patterns of performance -- good or bad -- proved inconsistent with their mandates.

In our efforts to serve the best interests of our fund shareholders over the long term, and to avoid making critical hiring and firing mistakes, we conduct direct, in-person meetings with portfolio managers and seek to understand the risks they take in order to achieve results. Face-to-face meetings with senior decision makers are the only way we can assess critical items such as investment process and culture and thus judge the repeatability of past performance. Specifically, we work to determine whether a manager's strong historical returns are simply a result of chance or if there is something else in place, be it a superior philosophy, a winning team dynamic or a proprietary edge in the investment process that competitors don't have.

The key to effective manager selection and oversight, we believe, is having an understanding of a strategy’s performance blueprint and determining whether a manager possesses the qualities necessary to make good investment decisions within that strategy consistently. More often than not, these characteristics come down to things like organization, culture, temperament, insight and experience. Only through meaningful discussion can one determine if an investment manager has what it takes to deliver repeatable results for investors.

Andrew Arnott is president and chief executive officer of John Hancock Investments, a wealth management business of John Hancock Financial, the U.S. division of Toronto-based Manulife Financial Corporation.