Populist movements garner significant attention but their lasting impact is questionable at best. These movements have increased in strength both domestically and abroad but very few have won national elections. At most, their movements can influence larger, more mainstream parties, but many of their messages and proposed polices have rarely come to fruition. Potential implications of renewed populism include a greater likelihood of new fiscal policy, a higher risk premium placed on financial markets, and a move back to more central-leaning party tendencies after a decade of increasing polarization. At the extreme, a third political party in the U.S. may arise.

A voter rebellion of sorts propelled both Republican candidate (and current presumptive nominee) Donald Trump and former Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders to greater than expected popularity in the 2016 primary elections. Although Sanders is no longer a contender in the 2016 presidential candidate, both his and Trump’s relative, and surprising, popularity reveals changing attitudes and growing frustrations with life in America that extends beyond discontent with Washington. Such attitudes and feelings are not just a domestic phenomenon, as the recent “Brexit” vote illustrated overseas. The United Kingdom (U.K.) held a referendum on June 23, 2016, to vote if the country should remain or leave the European Union (EU). In a surprising and unexpected outcome, a slight majority of voters approved what is known as “Brexit.”

NOT THE FIRST TIME

Populist ideology is certainly not new and prior historical episodes share similarities with today’s movements. In the U.S., populism movements date back over 150 years. The Know-Nothing movement in the mid-1800s originated out of resentment toward immigrants and fears of being displaced in the workforce (sound familiar?). A religious element (native born Protestant versus predominantly Catholic immigrants) was also a factor. The movement led to the rise the American Party, which carried some states and major cities in the 1856 presidential election, but it failed to garner any notable power and dissolved.

In the late 1880s, frustrated farmers and workers’ unions that grew distrustful of capitalism led to the rise of the People’s Party. The party won roughly 8% of the popular vote in the 1892 election, won a small number of states in the process, and remained a presence in politics before fading in 1896. A faction of the People’s Party, led by William Jennings Bryan, would remain a voice among the Democratic Party through the early 1900s. Bryan campaigned for President but failed again on his third and last attempt in 1908. Nonetheless, populist themes would influence, but not dominate, the Democratic Party in subsequent decades.

TODAY'S PARALLELS

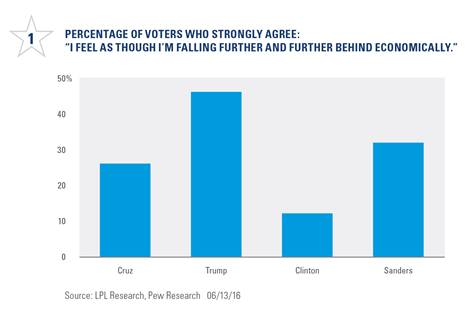

Unsurprisingly, both Trump and Sanders supporters exhibit strong dissatisfaction with the economy, consistent with prior bouts of rising populist sentiment. During the primary election season, each candidate ranked highest in the percentage who responded “strongly agree” to the statement, “I feel as though I’m falling further and further behind economically,” in a recent poll by the Pew Research Center [Figure 1].

Supporters of each also stand out relative to other candidates in their belief that “the old way of doing things no longer works and we need radical change,” with 55% of Trump supporters agreeing and Sanders not far behind at 41%. Frustration with the economy runs higher with Republicans generally, according to Pew, but Trump and Sanders stood out notably versus the other candidates.

ECONOMIC DISSATISFACTION

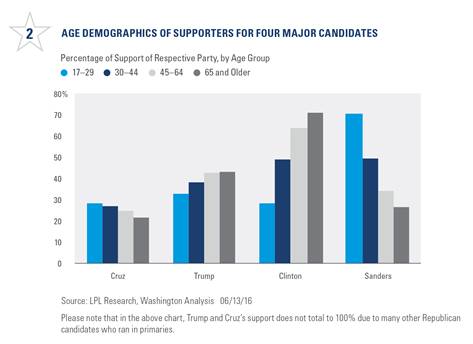

Economic frustration is common among younger voters who are upset with what they view as a lack of professional opportunities in the economy. Younger voters believe that income inequality is a major problem where the benefits of the economic recovery in recent years accrued mostly to those at the top of the income ladder. Sanders’s economic views seemed to capture younger voters’ frustrations, which were a clear driver of his popularity [Figure 2]. This younger generation is also saddled with the largest student debt burden of any generation and has put off marriage or buying a house partly in response to financial burdens. A sluggish economic recovery has made this angst linger and grow in intensity.

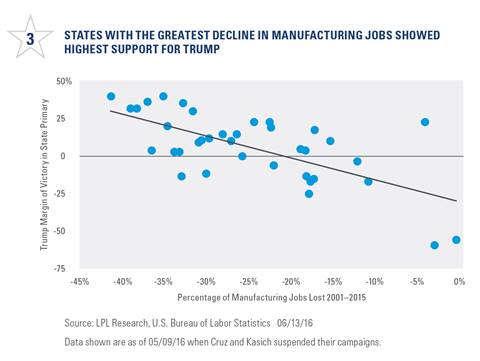

Many of Trump’s supporters were adversely impacted by the decline in manufacturing jobs over the years. The theme of limited job opportunities or struggles is similar to those gravitating toward Sanders. Early on, when Trump still faced opposite from other mainstream candidates, a clear trend became visible between Trump’s margin of victory in the primaries and the percentage of manufacturing jobs lost, by state [Figure 3].

Globalization and trade have been drivers of the slow decline of U.S. manufacturing jobs and Trump supporters are generally anti-trade and rank highest in anti-immigration sentiments. According to Pew, 69% of Trump supporters view immigration as a threat to job opportunities and a government that may be more stretched to provide benefits to a non-native population. The parallels to the 1850s are strong.

PASSION FOR CHANGE

The populist uprising may not win a popular election, but the passion for change may influence politics and policy over the next few years. Supporters of the populist movements believe the radical change they are demanding is part of something bigger that goes beyond the 2016 election. Almost 63% of Trump supporters strongly agree that “my candidate is leading a movement, not just a campaign,” and supporters of former candidate Sanders registered high at 56%. These are very elevated relative to former candidate Ted Cruz at 29% and presumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton at 26%.[1]

IMPLICATIONS

Improvement in the global economy could go a long way toward making domestic populist feelings dissipate. Better and more numerous job prospects may redirect energy. Still, the strength of populist convictions is not likely to fade away completely and may lead to other implications: greater prospects of new fiscal policy, higher investing risk premiums, and a move back to more central-leaning parties; or at the extreme, the rise of a third, perhaps more centrist, political party.

NEW FISCAL POLICY

The probability of some form of fiscal stimulus has likely increased as a result of rising populist sentiment and economic frustration. Infrastructure spending remains a frequent topic for potential policy. Congress is likely to remain a stumbling block for any fiscal policy but presumptive nominees, Clinton and Trump, have already voiced a desire to increase government spending. The last fiscal stimulus policy in the U.S., the American Recovery & Reinvestment Act (ARRA), phased out in 2011.

Calls for new fiscal policy may increase as the Federal Reserve (Fed) has done almost all it can do. Seven years of monetary stimulus in the form of interest rate cuts and quantitative easing (QE) bond purchases has likely run its course.[2] Politicians and individuals remain hesitant about the idea of increasing America’s debt, but 2016 primary results and data suggest that it’s time for Washington to get back into the act for the first time since 2011. An increasing debt load may be a small price to pay for the potential economic benefits (and jobs) of properly crafted fiscal stimulus.

RISING RISK PREMIUMS

The rise of populist movements may be one more factor to keep economic uncertainty high and investors on edge. Investors may exact a premium for such uncertainty. In addition to greater volatility (which has become more frequent over the past year), stock valuations (measured by price-to-earnings ratios) may remain in check and not rise as high. Investors may push up stock prices only so high given the uncertainty. In the bond market, lower bond yields reflect a premium on safety. Ultimately, the pace of the economy and financial shape of corporate America will have a greater impact on financial market returns but policy uncertainty could limit investment returns. The climate of shifting voter sentiments is unlikely to fade completely and may keep investors guessing as to the impact of policy change. Brexit is a good example of how a policy change has led to renewed volatility in financial markets.

A SWING BACK TO THE CENTER

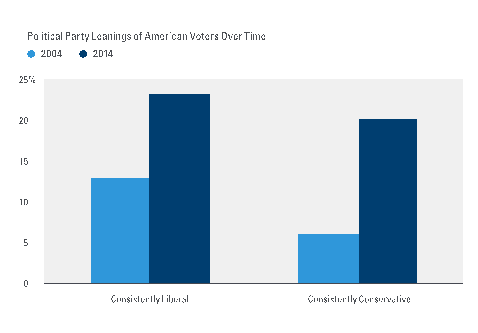

Increasing populist sentiment could drive political views and policy back toward the center after more than a decade of rising polarization [Figure 4]. At the extreme, a change to America’s political composition could develop over the long term. No group has emerged as a significant threat to either Democrats or Republicans, but Trump has shaken up the Republican Party and shown affiliation to both parties over the years. Trump’s proposed tax plans include a reduction in taxes but also the repeal of corporate tax breaks — ideas that span both parties’ ideologies. Conditions may be ripe for a third party, perhaps more centrist, to emerge and fill the gap left by both Democrats and Republicans.

CONCLUSION

Voter angst and frustration are driving populist sentiment globally, but history is full of such movements failing to win national elections or have a lasting impact. Recent events in Europe support this theme even after the Brexit vote results and Spanish elections. Domestically, the undercurrents of these populist movements, no matter who wins the White House in November, are likely to remain and have broader implications, including an increased probability of new fiscal policy, greater investing risk premiums, and a move to more centrist politics and policy.

Anthony Valeri is fixed-income and investment strategist for LPL Financial.