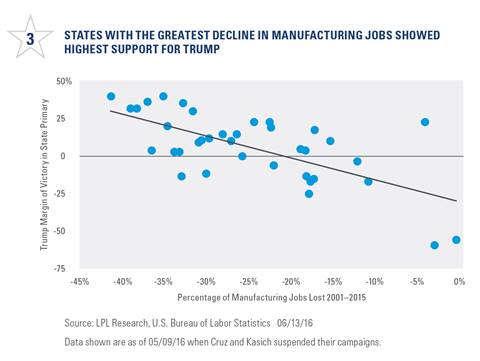

Many of Trump’s supporters were adversely impacted by the decline in manufacturing jobs over the years. The theme of limited job opportunities or struggles is similar to those gravitating toward Sanders. Early on, when Trump still faced opposite from other mainstream candidates, a clear trend became visible between Trump’s margin of victory in the primaries and the percentage of manufacturing jobs lost, by state [Figure 3].

Globalization and trade have been drivers of the slow decline of U.S. manufacturing jobs and Trump supporters are generally anti-trade and rank highest in anti-immigration sentiments. According to Pew, 69% of Trump supporters view immigration as a threat to job opportunities and a government that may be more stretched to provide benefits to a non-native population. The parallels to the 1850s are strong.

PASSION FOR CHANGE

The populist uprising may not win a popular election, but the passion for change may influence politics and policy over the next few years. Supporters of the populist movements believe the radical change they are demanding is part of something bigger that goes beyond the 2016 election. Almost 63% of Trump supporters strongly agree that “my candidate is leading a movement, not just a campaign,” and supporters of former candidate Sanders registered high at 56%. These are very elevated relative to former candidate Ted Cruz at 29% and presumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton at 26%.[1]

IMPLICATIONS

Improvement in the global economy could go a long way toward making domestic populist feelings dissipate. Better and more numerous job prospects may redirect energy. Still, the strength of populist convictions is not likely to fade away completely and may lead to other implications: greater prospects of new fiscal policy, higher investing risk premiums, and a move back to more central-leaning parties; or at the extreme, the rise of a third, perhaps more centrist, political party.

NEW FISCAL POLICY

The probability of some form of fiscal stimulus has likely increased as a result of rising populist sentiment and economic frustration. Infrastructure spending remains a frequent topic for potential policy. Congress is likely to remain a stumbling block for any fiscal policy but presumptive nominees, Clinton and Trump, have already voiced a desire to increase government spending. The last fiscal stimulus policy in the U.S., the American Recovery & Reinvestment Act (ARRA), phased out in 2011.

Calls for new fiscal policy may increase as the Federal Reserve (Fed) has done almost all it can do. Seven years of monetary stimulus in the form of interest rate cuts and quantitative easing (QE) bond purchases has likely run its course.[2] Politicians and individuals remain hesitant about the idea of increasing America’s debt, but 2016 primary results and data suggest that it’s time for Washington to get back into the act for the first time since 2011. An increasing debt load may be a small price to pay for the potential economic benefits (and jobs) of properly crafted fiscal stimulus.

RISING RISK PREMIUMS