Does international bond exposure belong in a target date fund (TDF) today? It’s a fair question in an investing environment where any potential source of portfolio return is getting a fresh look.

We believe, however, that the answer is a resounding no – and that any benefit to adding international bonds is considerably outweighed by the potential risks.

TDFs are complex solutions designed to balance a wide range of market conditions. As the dynamics shift and asset classes evolve, questions can emerge about whether a fund’s current “glidepath” – that is, its asset allocation over the years leading up to the targeted retirement date – remains appropriate for achieving the fund’s objective.

In particular, the question of whether adding international bond exposure to TDFs will improve diversification and generate stronger risk-adjusted returns has been a popular discussion point. We have looked at the question in depth, as part of our ongoing process of systematically evaluating inclusion of various asset classes including global and international bond exposures, in our firm’s TDF suite - LifePath®.

Even within our current capital market assumptions, our view is that adding international bonds does potentially improve diversification. However, the bonds also may introduce uncompensated currency risk and additional costs that act as a drag on performance, may increase exposure to countries with less financial stability, and will not meaningfully improve risk-adjusted returns.

Let’s take a look first at the diversification case for international bonds.

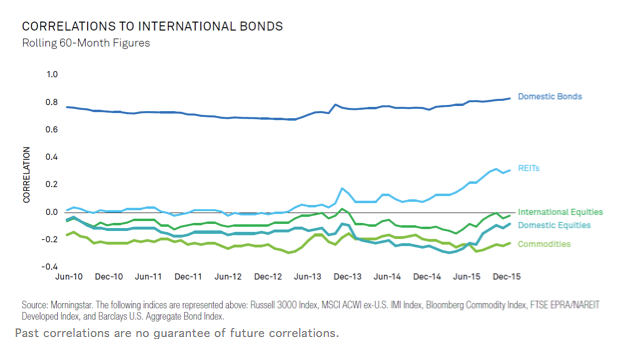

As the chart below illustrates (10-year data), returns for international bonds have exhibited low correlations to many broad asset classes, an effect that has held true for both currency hedged and unhedged exposures. There is no question that increased diversification is attractive, but the key question is whether the potential benefits can be captured in a cost effective manner.

When we take a look beyond the apparent diversification benefit, potential issues clearly emerge.

Uncompensated Currency Risk

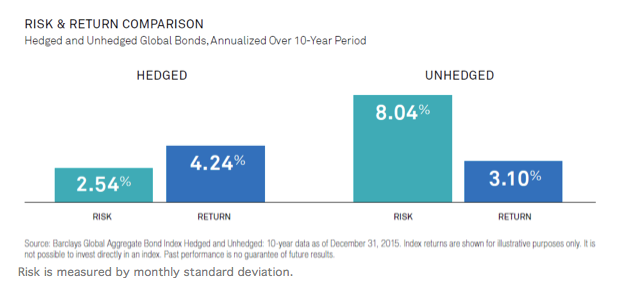

Over the past 10 years, currency volatility has represented about half of the total risk in the Barclays Global Aggregate Index. The impact is large, given the relatively low levels of absolute return generated by bonds. In the short term, currency exposure can be very volatile, but over longer time periods the expected return on currencies is zero. Accepting currency volatility is an uncompensated risk – which means that adding global bonds to a TDF introduces a generally uncompensated risk into that fund. That, in turn, drives the question and potential complexity of currency hedging.

Higher Transaction and Hedging Costs

Accessing global bonds remains relatively more expensive than transacting domestic investment-grade bonds due to lower liquidity and lack of transparency in the international bond markets. Currency hedging introduces additional cost (as well as complexity), which is estimated to be about 0.15% annually, rising during times of market stress. This added expense may be a drag on returns, eroding some of the modestly improved risk-adjusted return assumptions discussed above.

Macro Risk

A global bond allocation may increase exposure to countries with high debt-to-GDP ratios, as well as countries with higher political risk. This may increase the possibility of default risk in times of market stress. Conversely, it’s worth noting that in times of market stress, many global investors look to U.S. Treasury bonds as a safe haven.

Negative Yield

Further complicating the prospects for investment in global bonds is the current exposure to $9 trillion in negative-yielding securities. Negative yield means that investors buying debt now, and holding that debt to maturity, will receive less than they paid – clearly not a favorable outcome for plan participants.

Limited Effect on Risk-Adjusted Returns

We believe that the case to justify introducing an asset class into a TDF has to be strongly positive. However, our analysis indicates that the case for adding global bonds is weak indeed. When we analyze both historical performance and forward-looking market assumptions of various asset classes, in our opinion, replacing domestic bonds with an unhedged global bond exposure essentially offers no compelling return benefit, and in fact potentially produces inferior risk-adjusted returns in an asset allocation strategy. Adding hedged global bonds potentially improves risk-adjusted returns modestly – but hedging comes with added complexity and cost. Overall, the risk, return and diversification characteristics of the hedged global bond allocation are similar to that of domestic bonds. Simply put, in our view there is no strong incremental benefit in “going global.”

The Bottom Line

Our TDFs, like most, currently have their highest exposure to fixed income assets for those individuals at or in retirement – a period of particularly heightened risk sensitivity. Changes to the TDF allocation need to be weighed carefully and increasing risk, such as through currency exposure or regional political risk, should be carefully considered.

The TDF asset mix will always be a delicate balance, with nothing less than the retirement security of participants at stake. Our bias will be to avoid adding a new asset class unless, having considered all factors, we believe the anticipated improvement in risk-adjusted returns is sufficiently robust -- a position supported by careful analysis that always looks deeper than apparent advantages to identify the subtle risks, both for plan sponsors and for participants, that can lurk within an asset.

Matthew O'Hara is managing director and global head of investment research for the Lifetime Asset Allocation Group, BlackRock.