Investing Requires Resolve And Discipline

Stocks have taken a pounding and investor sentiment has cratered with uncertainty surrounding U.S. growth, global growth (especially in China), currencies, commodities, and Fed policy. There are many comparisons being made to the financial crisis which erupted in 2008, but we think there’s more different than similar. The financial system isn’t crumbling, and actually businesses are still relatively upbeat. Leverage in the financial system is a fraction of what it was in 2008; and while consumers—the major drivers of the U.S. economy—were heavily exposed to the financial crisis via housing; today they are on the “right side” of one of the causes of volatility by being oil consumers. Even if it gets worse from here before it gets better, remember that panic is not an investment strategy. It’s never fun to live through turbulent market times, but it can flush out some of the excesses in the market and set up the next move higher. As always, patience, diversification, discipline, and a long-term perspective are required.

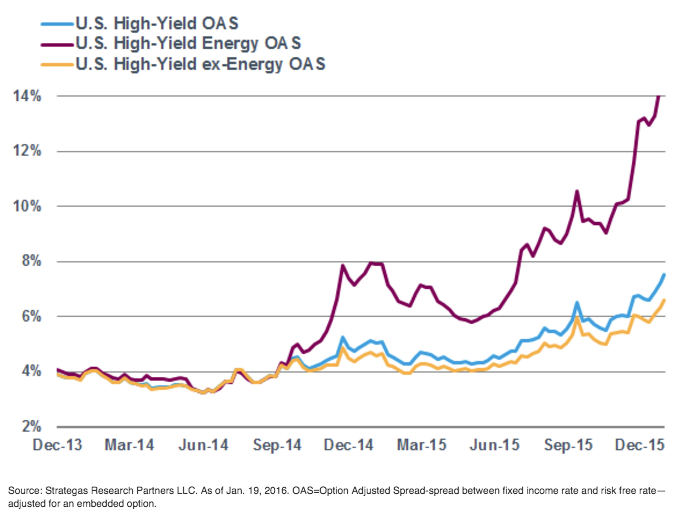

In that longer-term context, the recent move isn’t all that rare. According to FactSet, since 1928, on average a 10% correction has occurred every 1.58 years; while during this bull run that began in 2009, we have only experienced three. But what was the impetus behind the recent selling and is it foretelling something more ominous? Global growth worries, centered in China, seem to be part of the reason, expressed most readily by the continuing drop in a broad selection of commodity prices, with oil being at the top of radar screens. As the drop in oil has decimated the energy market, worries have escalated that the drop is foretelling a serious economic problem, while also raising the risks of a financial accident due to increasing defaults on energy company debt—illustrated by a spike in US high yield energy rates.

Perceived Energy Risks Have Risen

And there’s no doubt defaults will rise as revenues have cratered, but we point out again that the financial system is in much better shape than it was in 2008, with much larger capital cushions; while major bank exposure to energy companies appears at this point relatively limited. Some regional banks may feel some pain, but there doesn’t currently appear to be a large systemic problem in the cards.

Unquestionably, the speed at which the headwinds associated with plunging oil prices are blowing (i.e., the hit to the energy sector and earnings) is presently sharply faster than the speed at which the tailwinds are blowing (i.e., the benefit to the consumer and energy-consuming companies). So for now, the race is being won by the negative effect.

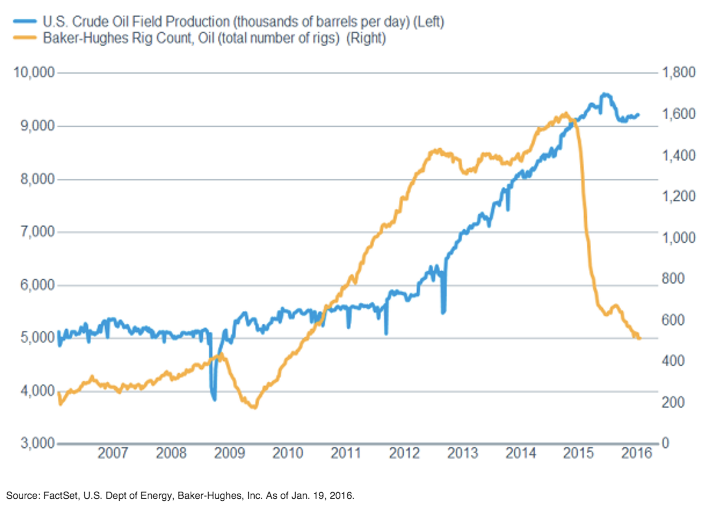

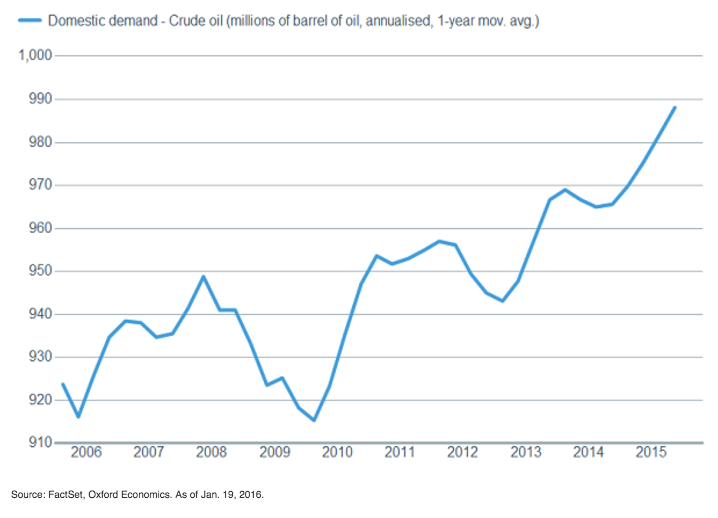

While we aren’t going to hazard a guess at where the bottom in oil may be, we do likely need to see some stabilization before market volatility can ease. This stabilization could be aided by a continued drop in the rig count, U.S. production growth decreasing, and global demand picking up. As is often said, the cure for low oil prices is low oil prices, as it typically stimulates higher demand and lower supply.

Rigs Have Fallen And Production Is Starting To Follow

While U.S. Demand For Oil Is Rising

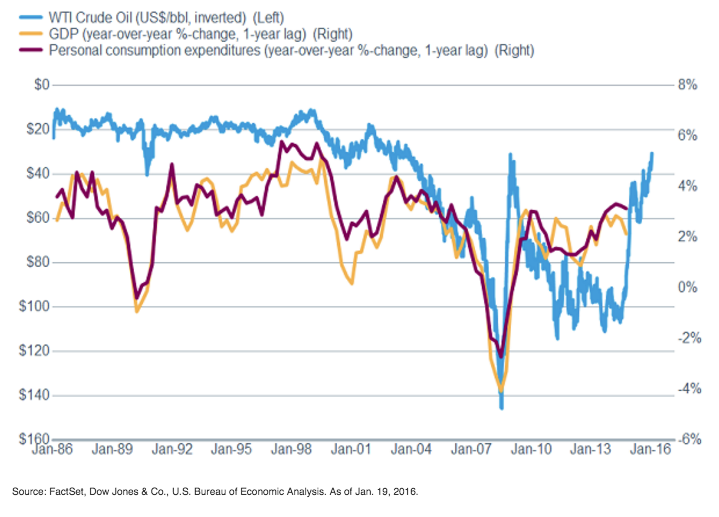

Economy Not Falling Off A Cliff

As noted, lower energy costs are ostensibly a boost to the consumption-oriented U.S. economy. To get an idea of the scale of the energy sector, Cornerstone Macro reports that in last year’s third quarter, oil and gas capital expenditures (capex) made up about 4% of total capex—not nothing, but relatively small as a share of the economy. And as the chart below shows, oil prices have led economic growth and personal consumption by about a year, with a negative correlation, meaning lower prices have led to higher growth a year later, something we could start to see this year.

Foretelling A Surge In Growth?

Company commentaries during reporting season have taken a back seat to macro concerns, but have contained little in the way of panic or dire predictions. There have been some business specific problems to be sure, but outside of the energy and materials groups, most companies have been noting fairly solid demand and are meeting or beating profit estimates. December 2015’s National Federation for Independent Business (NFIB) report showed that small business confidence rose slightly, as did hiring plans; while the plans to raise compensations stayed at a solid 20%. And the job market continues to be quite healthy, with unemployment remaining low at 5%, and forward-looking initial jobless claims continuing to be near historic lows.

Jobless Claims Not Flashing A Warning Sign

And a number not highly followed but mentioned as important by Fed Chair Yellen, the JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) “quit rate” rose to 2.83 million in November, the highest level since April 2008, indicating increasing confidence among job seekers. And this is contributing to both modestly improving wages and slightly stronger consumer spending, which should help to support the U.S. economy, and eventually, U.S. stocks.

Wages Moving Higher

Fed In Holding Pattern

The combination of the tumult in the equity market and the continued rout in oil/commodities, combined with the lack of inflationary pressures, will almost certainly mean the Fed will make no move at its upcoming meeting ending January 27. It’s too soon to say whether the Fed will move at its March meeting; but we are fairly confidence the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will lower its projections for rate hikes this year from a total of four to closer to what the market’s been expecting, which is no more than two. The Fed continues to telegraph the desire to move slowly and deliberately, but it also seems the majority of FOMC members want to move further away from the extremes of its zero interest rate policy (ZIRP).

Lack Of Excess

Volatility abounds across the globe, with fears of major economies breaking down dominating investors’ attention and headlines. Recession risk is up, but not likely to the degree fears are up. Drivers of recessions and bear markets have been varied in the past, but they typically come when excess has built in the economy—typically in spending, lending, inflation, and/or monetary policy.

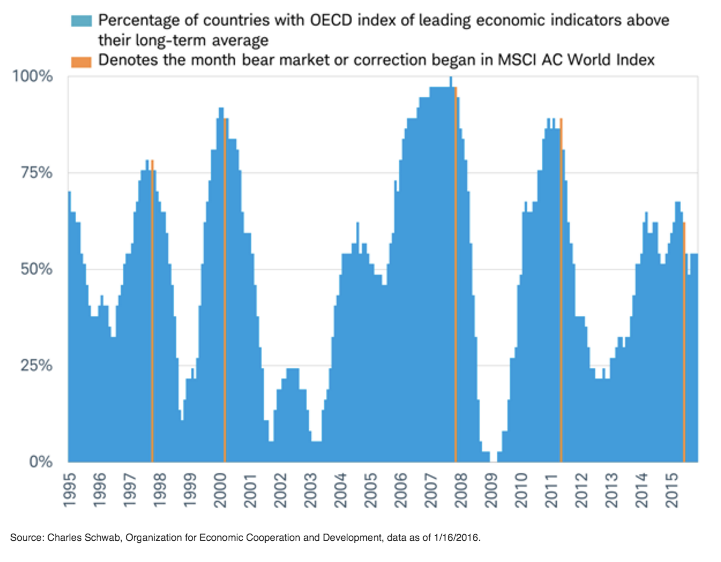

The International Monetary Fund has used a global annual real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 3.0% or less as a guideline for defining a global recession. Using that guideline, over the past 20 years there have been four global recessions. As each of the downturns began, global stocks fell into bear markets, measured as a 20% or more decline from the peak in the MSCI All-Country World Index. As you can see in the chart below, one way to see the start of these bear markets is by the peaks in the percentage of countries with their index of leading economic indicators above the long-term average.

Leading Economic Indicators And Bear Markets

In recent years, global growth has not been as strong nor as widespread as it had been in past periods of growth. This may mean that the build up of excesses and imbalances that ultimately lead to a global recession have not yet reached a level that makes the global economy vulnerable to a prolonged downturn.

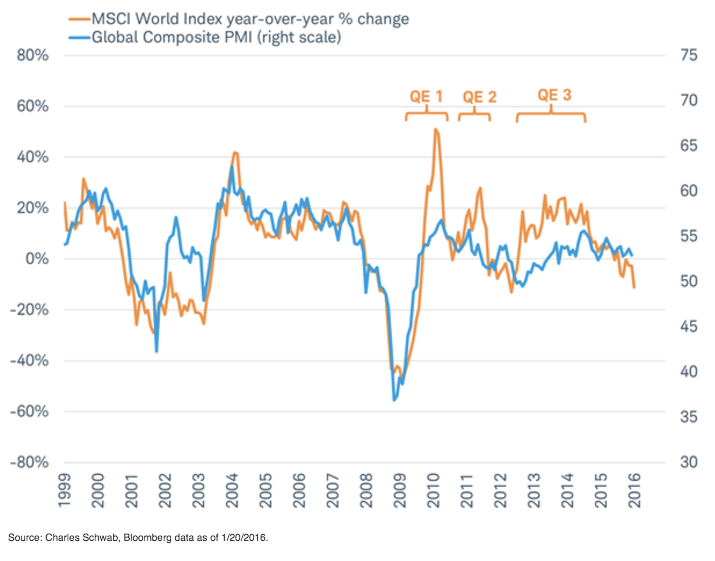

Market Overshoots

The overshoot to the downside in global markets relative to the global economy can be seen in the chart below. The world’s stocks tend to closely track the global composite purchasing managers index, a measure of global economic activity. The exceptions were when the Fed’s QE programs temporarily boosted stocks without a similar effect on the global economy. Stocks have priced in a drop from the December reading of 52.9 to just below 50, a level coincident with global recessions in the past.

Global stocks overshoot global economy

While global stocks markets are increasingly pricing in fears of a prolonged global recession, the global economy has yet to weaken significantly or reflect excesses that make it especially vulnerable to the risks posed by falling oil prices, slowing Chinese economic growth, or a slow and measured pace of Fed rate hikes.

So What?

It can be difficult to stay calm during market declines, but reacting emotionally is rarely beneficial. Investors need to maintain discipline and keep long-term goals in mind. Risks have risen for the U.S. and global economy, but neither a domestic nor global recession appears to be on the imminent horizon. But oil likely needs to stabilize to stem some of the recent volatility. Stay calm, and don’t overreact to the short-term gyrations in the market.

Liz Ann Sonders is senior vice president and chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.

Brad Sorensen is managing director of market and sector analysis at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Jeffrey Kleintop is senior vice president and chief global investment strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.

This article can also be read here.