When I was growing up, there were only five television stations available. We got two bursts of news: national news at around 6 p.m. and local news at 10 p.m. We didn’t always have up-to-the-minute information, but we did have some time to reflect.

Today, by contrast, we are overloaded with high-frequency communication. We have business networks, countless internet sites and social media all providing continuous news and opinion. Some still exercise some editorial influence before publication, but many don’t. At times of high uncertainty, the dissemination of “information” can create more confusion than clarity.

The downside of today’s media model has been on prominent display in the days since voters in the United Kingdom (or should I say 36% of registered voters in the United Kingdom) expressed a wish to depart the European Union (EU). In the aftermath, analysts began to project a wide range of separations occurring within regions and countries. It was as if the map of Europe were heading back to its standing of 400 years ago.

There is certainly much that is still up in the air. But allow us to offer an update on the key issues for Europe in the wake of “Brexit.”

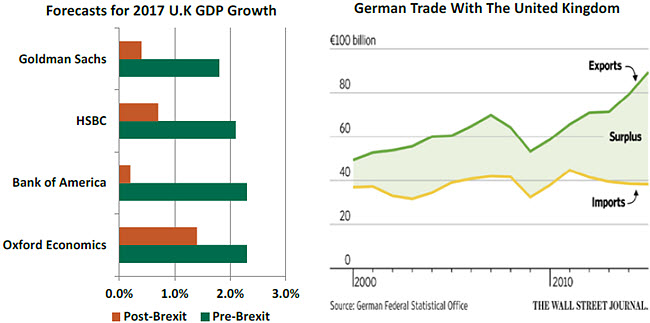

1. The U.K. economic outlook has become very tenuous. Forecasts for gross domestic product (GDP) growth were revised substantially downward in the past weeks. Firms desiring to ensure continued access to the EU market may move some operations out of the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom may have to renegotiate trading terms with a series of global counterparties. And the heightened level of uncertainty won’t help business or consumer spending.

This is all bad for the United Kingdom, but also bad for those who count the country as a client. The United Kingdom is Germany’s third-largest export market, which will undoubtedly influence German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s posture in departure negotiations. She will have to talk tough publicly, as a warning to other potential separatists. But behind closed doors, she (and other EU leaders) may be more accommodating.

It may seem far off at the moment, but there are at least a few reasons to think that a productive new relationship can be defined. But that may take a while, because …

2. The politics on both sides of the separation are deeply complex. After some initial turmoil, the London Stock Exchange enjoyed a nice recovery. But the political turmoil in the United Kingdom could drag on for several more months, heightening uncertainty.

With U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron set to step down, candidates for Tory primacy stepped forward on Thursday. Unexpectedly, the main favorite, Boris Johnson, ruled himself out of contention. A new leader will be chosen at the party’s Congress in October. Meanwhile, the opposition Labour party is on the brink of complete implosion. Its leader, Jeremy Corbyn, lost a vote of no confidence by an overwhelming margin last week but has refused to step down.

In the northernmost part of the country, Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has pledged to protect Scotland’s interests in the European Union. Sturgeon has already voiced the idea of a second Scottish independence referendum, a scenario which now looks increasingly likely.

It is difficult to recall a time when U.K. politics have been so deeply fractured. There is a massive power vacuum at a time when clear leadership is desperately needed to calm investors.

Presuming the various parties get their acts together, attention will turn to how the government goes about invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, the first step in separation discussions. Such an action will need to be approved in parliament, meaning there is a chance it could be voted down. Politically, though, it would be very tricky to go against the result of the referendum, even though the result is not binding.

Other European leaders have given mixed signals over the speed with which they expect exit negotiations to begin. Some want to start almost immediately, while Chancellor Merkel has counseled patience. However, one message has been made abundantly clear – the United Kingdom will not retain access to the single market without paying dues to Brussels and accepting the free movement of labor. Those, of course, were the two biggest bones of contention for the “Leave” supporters.

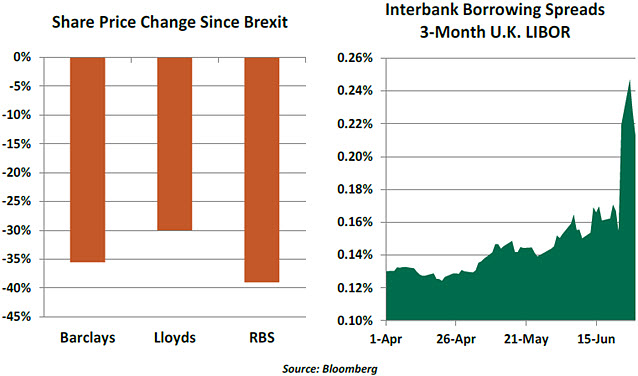

3. The situation has stressed U.K. banks. Post-Brexit challenges could cause U.K. house prices to fall, unemployment to rise and corporate insolvencies to increase, all contributing to asset quality deterioration. In response, the Bank of England (BoE) may reduce its interest rates, which would increase pressure on bank margins. BoE Governor Mark Carney signaled as much this week, suggesting that Britain was suffering “economic post-traumatic stress disorder.”

U.K. sovereign downgrade risk has risen, which will negatively affect bank credit ratings and the cost of funding to the financial sector. The rapid realignment of currencies may create trading losses for some. Few expect any of the big U.K. banks to fail, but their challenges will serve as a further drag on economic prospects.

Carney was the Governor of the Bank of Canada before taking over at the BoE. He is well-versed in the central bank crisis playbook: get engaged early, talk aggressively, follow the talk with substantial action and promise to keep the stimulus coming. We’ve wondered how a central bank that pulled out all the stops after 2008 would respond to a fresh crisis. We are about to find out if the BoE has any “dry powder.”

Institutions on the other side of the English Channel, some of which never completely healed from the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent European peripheral debt crisis, could feel renewed stress. Unfortunately, the European Central Bank (ECB) isn’t in a position to provide much more support to the beleaguered eurozone banking community. ECB President Mario Draghi called this week for close coordination with the BoE and the Federal Reserve.

Very low interest rates in developed economies, volatile markets and risk aversion remain the early consequences of Brexit. For now, there has been no significant impact on economic or market performance in the United States or Asia. But if instability persists, no one will be immune.

No one wants to go back to the old “rabbit-ear” antennas that filled our TV screens with snow. But we’ll have to keep our antennas sharply tuned in during the coming weeks to get a clear image of what’s going on in Europe and what it means for the rest of the world. Stay tuned.

Raghu’s Resignation

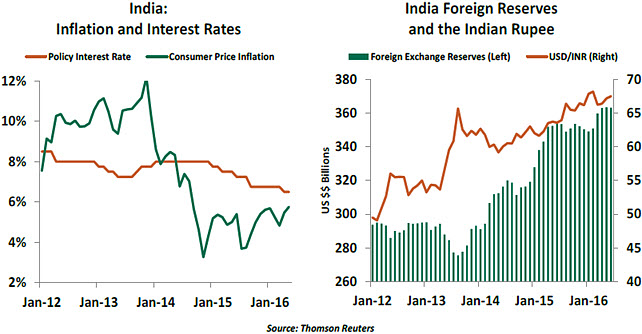

Raghuram Rajan has decided not to seek a second term as the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and instead will return to the University of Chicago (U of C) after September 2016. The departure of any official is never a question of “if” but one of when and how. Recent events suggest that the Indian government pushed him out.

Although the RBI has had many distinguished governors in its 81-year history, Rajan is certainly the most globally well-known and conspicuously independent of the lot. He had a long academic career at U of C’s Booth business school, spent three years as chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and was one of the first voices to warn in 2005 of the impending global financial crises. He also spent a year as the chief economic advisor to the Indian government, rounding out a stellar background that he brought to the RBI’s helm.

Joining the bank during the so-called “taper tantrum” in September 2013, Rajan had a crucial role in stemming a currency crisis in India. Since then, he has focused on taming inflation, stabilizing the rupee, building foreign exchange reserves, introducing inflation targeting, and cleaning up non-performing loans in the public sector banking system.

At most times, monetary policy is not rocket science. There is a standard policy reaction for taming inflationary expectations, or to stop a run on the currency. However, personality matters when tough choices are at hand. Rajan was able to leverage his credibility with the international financial community to push ahead with decisions that would otherwise earn the wrath of the government or vested interests.

By objective standards, his tenure was a great success. Therefore, it came as a shock when, after consulting the government, he decided to not seek a second term.

Since the economic liberalization of 1991, the RBI has earned a reputation for independence. Its standing may not be at the level of central banks in developed markets, but the RBI certainly stands head and shoulders above most of its peers in the developing world. The RBI’s leaders and Indian finance ministers have publicly disagreed in the past, but every RBI governor in the last 25 years was granted a second term, despite regular changes in government.

The decision to elbow out Rajan suggests a new regime is in place. His opponents are not fans of monetary restraint, and speculation swirls that “big business” — hurt by the cleanup of the banking sector — forced the government’s hand. Rajan may not have helped himself by commenting on social issues or by being too frank about India’s economic situation.

But his departure shows the government in a poor light, suggesting a lack of understanding about the importance of a credible and independent central bank governor.

The incoming governor not only must live under Rajan’s shadow but will have to fight the perception of being a rubber stamp. A quick announcement of a credible, independent and articulate RBI governor will be essential to India’s continued economic success.

The Power of Crowdsourcing

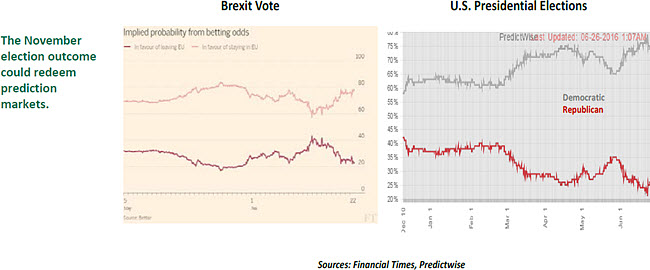

People in ancient times sought answers about the future from Pythia, the Oracle of Delphi. Today, polls, statistical models and prediction markets are the means used to foretell the future. The latter method played a central role in the run-up to the Brexit vote – and failed miserably.

In prediction markets, participants trade in contracts whose payoff depends on the outcome of future events. A prediction market asks a yes/no question. “Do you think Trump will be elected president?” “Do you think ‘Star Trek Beyond’ will be a success?” The answers are then turned to a probability. If 65% answer “yes,” that becomes a contract you can buy or sell. If the ultimate payout is set at $10, you buy the contract at $6.50. If it turns out right, you make $3.50; if you are wrong, you get nothing.

Prediction markets work with real money, funny money, small prizes and vouchers. The “odds” they produce are not just a product of how many people are on one side or the other but also how much they are willing to wager on the outcome.

Research indicates that prediction markets have produced better forecasts than other methods in a range of domains, including elections, sports, business propositions and entertainment. But they failed with the Brexit vote. Speculation around the cause of the failure centers on large bets placed by a small community on “Remain” that was very slow to adjust its initial beliefs, even as the “Leave” movement gained momentum.

At the moment, betting markets suggest that Donald Trump has just a one-in-four chance of becoming the next U.S. president. We’ll see if those odds prove correct next November.

Carl Tannenbaum is the chief economist for Northern Trust.

Asha Bangalore is senior vice president and economist at Northern Trust.

Ben Trinder is a London-based analyst with the country risk unit at Northern Trust.