Some insurers may already be feeling the burden of increasingly sick patients. Anthem’s then-Chief Financial Officer Wayne DeVeydt said in April the company was “disproportionately picking up market share” in states where co-ops had folded. On a July conference call, Chief Executive Officer Joseph Swedish said that as the insurer had brought in new membership, its costs of caring for patients with heart disease, diabetes and especially dialysis had increased. Jill Becher, an Anthem spokeswoman, said the CEO’s comments referred to the company’s overall ACA membership.

The company expects to break even on its ACA business next year and return it to profitability in 2018, Swedish said last week at a conference in New York. Still, some analysts aren’t convinced. David Windley, an analyst at Jefferies LLC, cut his rating on Sept. 13 to “hold” from “buy,” citing in part Anthem’s “potential to inherit sick members from peers exiting exchanges.”

Aetna and Humana Inc. are each on track to lose at least $300 million on Obamacare this year and have joined rivals in leaving many areas where they sell ACA plans. The broad retreat of payers -- including co-ops -- “is one of the contributing factors to our inability to responsibly maintain our current footprint,” T.J. Crawford, an Aetna spokesman, said by phone.

Many Miscalculations

Representatives of Humana didn’t respond to calls seeking comment. Tyler Mason, a spokesman for UnitedHealth, declined to comment. Both insurers sold Obamacare coverage in states where co-ops have closed, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Jason McGorman.

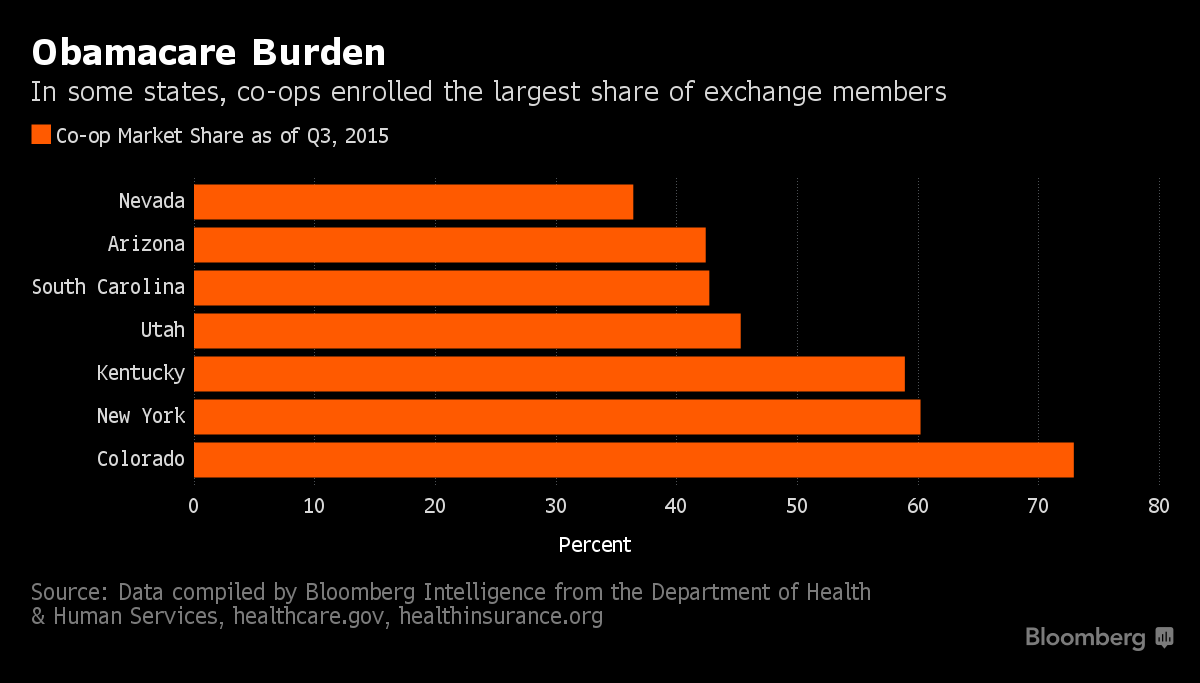

The demise of 17 of the 23 original co-ops came after many miscalculations. The nonprofits priced plans lower than private insurers in many states, attracting large memberships that exceeded enrollment projections by as much as three times, according to Scott Harrington, a professor of insurance and risk management at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

As enrollments rose, so did costs. In states like Kentucky, Nevada and South Carolina, co-ops struggled with members who had never before had coverage and required more treatments, former executives said.

South Carolina’s co-op patients “skewed older and had higher medical needs,” said Jerry Burgess, who was chief executive of the now-defunct Consumers’ Choice Health Insurance Co., in a telephone interview. “If we took in a dollar on premiums, we were spending a dollar on medical expense. You can’t sustain that, you’re in a loss position.”

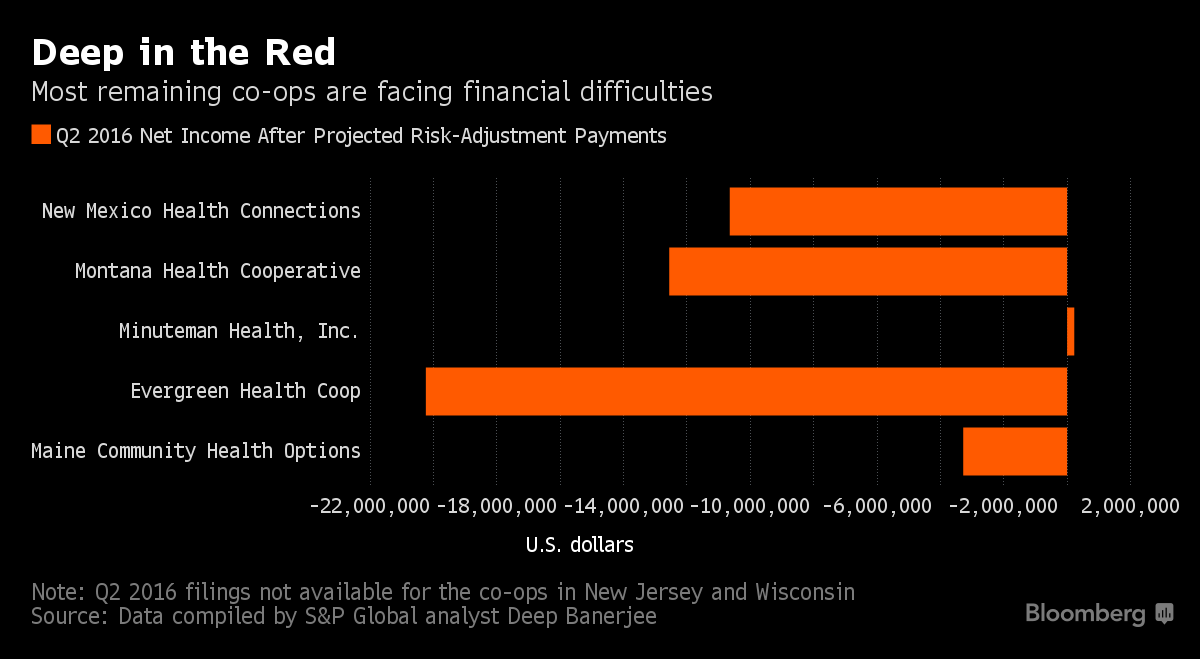

Co-ops were also hurt by an ACA program intended to transfer funds from insurers with healthier customers to those with sick ones, called “risk adjustment.” The program considered many of the co-ops’ members to be healthier than those with other insurers, though the co-ops say that’s not the case.

Because of risk adjustment, the co-ops were sometimes required to pay hefty sums to larger rivals. Some have sued federal officials over the program, seeking to avoid making the payments. While Albright, the CMS spokesman, declined to comment on the lawsuits, the agency has proposed implementing some of the insurers’ suggested changes.