Hedge fund strategies frequently outperformed the S&P 500 Index from 1992 to 2007, and most pre-2008-financial-crisis academic studies found that hedge funds, on average, generated positive alpha. But "hedge funds overall didn't perform as well as people would have expected during the crisis," says Mallory Horejs, an alternative investment analyst with Morningstar.

Although some hedge strategies provided significant downside protection at the time, many correlated with the broader market and posted negative returns, defeating one of the main purposes of investing in hedge funds: making money in any market, particularly during down periods. "The whole concept of absolute, uncorrelated returns really flew out the window," says Horejs.

Less than stellar performance wasn't the only issue, she adds. "Many hedge funds imposed gates on their assets, preventing investors from withdrawing their money even as the market continued to drop," she says. Some hedge fund investors got burned as a result. "They didn't realize the potential was there to lose all their money."

For private wealth advisors, the question is, in the aggregate, do hedge funds presently add value? In other words, are hedge funds, and especially funds of hedge funds (FoFs), creating enough alpha after fees and taxes to justify the illiquidity and other risks associated with investing in them?

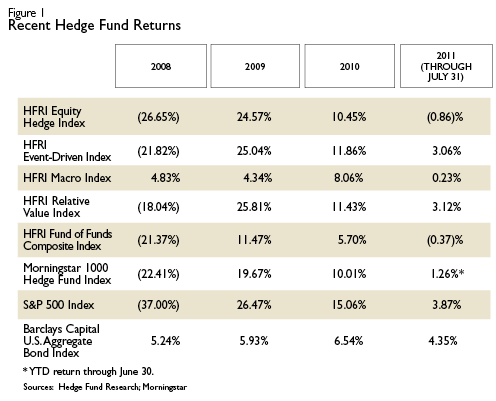

If we go by Figure 1, the quick answer appears to be, "no." The table shows, among other things, that the Morningstar 1000 Hedge Fund Index, a composite of the largest hedge funds in Morningstar's database, has lagged the S&P 500 since 2009, although it has beaten the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Bond Index until recently.

Determining whether this asset class is appropriate for clients begins with a clear understanding of these funds. The word "hedge" might invoke images of investors prudently covering their bets. But hedge funds can be highly risky and super-volatile. In fact, dozens of hedge funds have suffered serious losses, shut down or filed for bankruptcy in recent years.

Being relatively unconstrained by SEC regulations that apply to mutual funds, hedge fund managers can and do use leverage, take short positions and invest in derivatives. Overall, hedge fund managers employ an estimated 15 to 20 different types of strategy, which Hedge Fund Research, the largest industry data tracker, groups into four broad categories, as Figure 1 indicates.

For their vaunted expertise, hedge fund managers typically charge high fees, which industry critics cite as a value detractor. The industry average is the so-called "two and 20," 2% of AUM and 20% of the profits. In practice, management fees range from 1% to 3% and performance fees can be as high as 40% of the fund's upside.

A fund of funds is even more expensive because investors pay a management fee and a performance fee for each underlying fund, plus the same to the FoF manager. FoF management fees average 1% per year and incentive fees are typically 10%. For the extra layer of fees, FoF managers provide investors with asset allocation and perform due diligence on the underlying funds. FoFs often require lower minimum investments than individual funds and can provide clients with access to single funds that may be otherwise closed to new investors. Multi-fund strategies can also help minimize the risk of an individual fund imploding and wiping out all of an investor's capital.

Historically, FoFs have touted their multiple holdings as a diversification tool, but new academic research demonstrates that once a fund of hedge funds holds more than 20 underlying funds, the benefit of diversification drops sharply. A July 2011 study, by New York University Professor Stephen Brown and two co-authors, available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1436468, found that more than 20 underlying funds increases risk in extreme market conditions.

The increased risk was accompanied by lower returns due to the expense of necessary due diligence, the price of which increases with the number of underlying FoF funds. The study also noted that the majority of FoFs hold more than 20 individual funds.

Taxes have a further impact on returns. Because some managers trade frequently in an attempt to create outsized returns, their funds generate significant short-term capital gains for investors that are taxed at ordinary rates.

Fresh Scenery

Despite these issues, advisors shouldn't dismiss hedge funds altogether. As of the end of June, the hedge fund industry was at peak assets-just over $2 trillion. New allocations to hedge funds exceeded $60 billion in the first half of 2011, higher than the total for all of 2010.

According to the 2011 Prequin Global Hedge Funds Investor Report, hedge fund investors were once primarily high-net-worth individuals. But the hedge fund landscape began to change after the 2008 financial crisis when individual investors, frustrated with the excessive fees and sagging performance of the overall hedge fund industry, moved out of the space and institutional investors began to dominate the asset class.

As more institutional money rushed into hedge funds, the balance of power between investors and fund managers began to shift. The leverage that institutional investors brought to the negotiating table allowed them to bargain for reduced fees and shorter lock-up periods, according to Prequin. The institutional investors who now rule the asset class favor bigger funds, in part because larger funds have better risk management and more compliance infrastructure, according to Prequin.

A recent Morningstar report confirms that the largest hedge funds are only growing larger. During the first quarter of 2011, the top 20 individual funds in Morningstar's database had 25% more in AUM than they did one year previously, while the next 20 largest funds managed only 10% more in assets over the prior year.

But perhaps the most significant post-crisis change in the hedge fund industry was investor demand for greater visibility, according to Kenneth J. Heinz, president of Chicago-based Hedge Fund Research. "The evolution of the industry, with regard to transparency, hit a key inflection point in December 2008, as a result of the disclosure of the financial fraud associated with Madoff Securities," he says.

Heinz thinks the industry has become a much better place to invest. "Managers are more responsive to investors in terms of due diligence," he says.

Finding Value

Alan Lenahan, director of Hedged Strategies for Cincinnati-based Fund Evaluation Group, an investment advisory firm, expects to see renewed and growing interest in hedge funds from high-net-worth investors, whether via single strategy funds or FoFs. Lenahan predicts "a sifting through of providers" where investors pick out higher-quality managers that came through 2008 and the last few years in better shape than their peers.

"There's been a lot of media negativity that has scared people," he says. Despite the bad press, Lenahan maintains that hedge funds are still a good way to provide diversification and stable returns, protect capital and reduce risk in a portfolio.

But finding the lonely star performers in the vast universe of hedge funds is not an easy task. Fund Evaluation Group devotes significant resources to doing just that. Yet few individual funds meet the firm's strict criteria for recommendation to its large clients, or for inclusion in its proprietary FoFs. Even funds that are top quartile performers throughout their lives will not pass muster unless they follow best practices across the board in terms of operational processes, financial controls and regulatory compliance. "There are 9,000 hedge funds," Lenahan says. "There are probably 200 or 300 that matter to us. There's an unbelievable amount of noise."

So how does an advisor who's considering putting clients' money into hedge funds, or FoFs, eliminate the "noise" and determine whether the potential rewards of investing in a particular fund or FoF outweigh the risks? The answer may well start with seeking out those funds and FoFs that attempt to align manager and investor interests. The first step in this process is what Lenahan calls "conviction," the expectation that if fund managers believe in their products, they will have a substantial portion of their own assets in the fund they're promoting.

Other clues to alignment of interests are hurdle rates and clawbacks. Hurdle rates prevent fund managers from receiving performance fees on any gains they make unless they exceed a certain threshold, such as the ten-year T-Bill rate, or a certain percentage (e.g., 5%), although they still receive their basic management fees regardless of whether the fund exceeds the hurdle. Clawback provisions in contracts allow investors to recover performance-based compensation if future events demonstrate that managers received excessive or unearned profits through, for example, manipulation of financial results.

Because of the complexity and opacity of hedge funds and their strategies, industry experts recommend outsourcing the hedge fund selection process to qualified professionals. "There's a very specific and intense effort that has to occur on research, sourcing and due diligence. It takes a team and a dedicated focus to do properly," says Lenahan.

Advisors should look for experts whose screening process includes filtering information from high-quality, proprietary databases and ensuring that funds are following operational best practices-a key component in minimizing fraud risk. Interviewing managers, performing background checks and site visits, verifying relationships with prime brokers and with outside legal and accounting firms and reviewing all relevant legal and financial documents should also be part of the process.

Alternative Hedges

John Osterweis, chairman and CIO of San Francisco-based Osterweis Capital Management, thinks many individual hedge funds add value, but that there are also many that do not. A lot of hedge funds don't hedge effectively, he adds.

Advisors don't necessarily need exotic strategies, with their accompanying high fees and low transparency, he says.

Osterweis, for example, prefers to use fixed income as a hedge against downside risk, to decrease volatility and to provide income for his clients' portfolios. He runs what he calls "a very simple, dynamically balanced fund," the Osterweis Strategic Investment Fund. He varies the ratio of stocks and bonds in the portfolio by up to 75% stocks, 25% bonds, or vice versa, according to anticipated market conditions.

Osterweis says that over long time periods, "the old 60/40-60% stocks, 40% high-grade bonds-was in fact a pretty good hedged book. In any serious bear market, the high-grade fixed income produced a positive return because of the flight to quality. If there's another melt-down in the stock market, investment-grade bonds are going to do a heck of a lot better than stocks."