But the notion of another snapback isn’t universally accepted, at least not one that comes anytime soon. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development warned in a recent study that the risk of slower global growth is a key challenge in the decades ahead. “Global growth prospects seem mediocre compared with the past,” according to the group’s recent paper, “Policy Challenges for the Next 50 Years.” Emerging markets are still expected to rise faster than developed nations, but the edge is projected to fade because of “a gradual exhaustion of the catch-up process and less favorable demographics in almost all countries.”

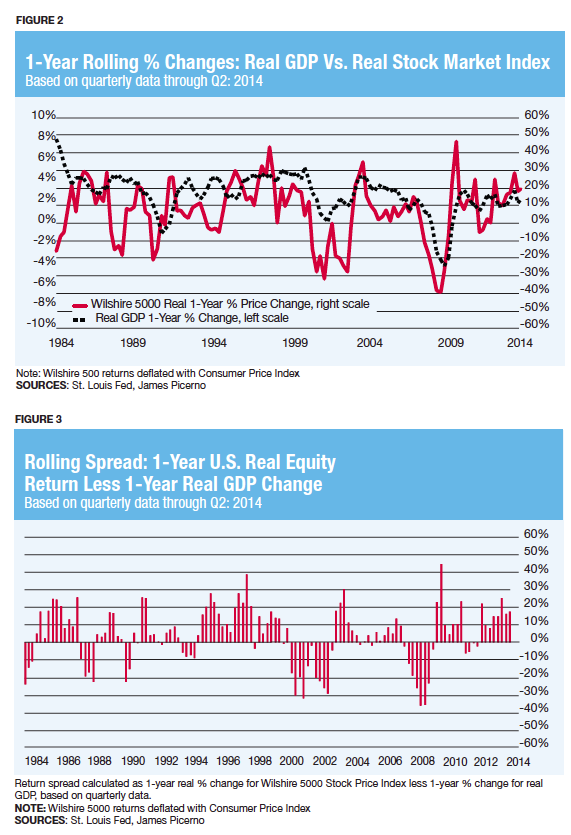

If growth is slowing for an extended period, what does that imply for returns on risky assets—stocks in particular? The answer varies depending on your time frame and economic assumptions. But this much is clear: There’s a generally close relationship between changes in the economy (GDP) and equity returns across the decades, as Figure 2 shows.

Equity returns may wander off on their own in the short run. But expecting stock performance to disconnect from the real economy for any length of time is expecting too much (Figure 3). If economic growth is slow, it will eventually catch up with investors.

All Together Now

Bill Bernstein, a widely read financial planner and the author of several best-selling investment books, isn’t particularly worried about slower economic growth. He’s more worried that correlations among investments will increase.

He thinks diversification through conventional asset allocation strategies will be under pressure in the years ahead. “As markets become ever more connected, ‘short-term’ correlations are rising,” he said in an interview with Financial Advisor.

He outlined the case for this future in his 2012 booklet Skating Where the Puck Was: The Correlation Game in a Flat World. The payoff for diversifying into so-called alternative asset classes will likely fade in the years ahead, he writes. As markets become ever more globalized, and the financial industry persists in securitizing assets that were once obscure, investors will get less bang for their buck by adding formerly exotic assets such as commodities, foreign securities and real estate investment trusts. It won’t juice performance or curtail risk as well.

The problem is that good news travels fast. As the crowd loads up on “new” asset classes and chases a finite supply of them, the features that made them so attractive in the first place—low correlations with stocks and bonds and relatively high expected returns—tend to fade.

“Elders of the investment tribe long enough in tooth will recall the refrain of a popular song from the distant 1970s,” Bernstein writes. “‘Call someplace paradise, kiss it goodbye.’ Well, the same is generally true of diversifying asset classes: As soon as a new one gets discovered, it’s already gone.”

Slow-Growth Debate

November 3, 2014

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment