Volatility – and how to find shelter from it – has become a common denominator in conversations regarding asset allocation lately.

This defensive response has left investors with plenty of residual cash. Already, many investors have increased their strategic allocations to cash and cash-related instruments (“cash”) in recent years, which is, in and of itself, a fundamental change in asset allocation. Cash has indeed moved from apathetic afterthought to a structural component of portfolio composition.

Cash investing is changing, and many investors may need to increase their awareness of the new landscape to invest successfully for capital preservation today. We have identified three critical changes for investors to watch.

3. Regulatory reforms are changing the risks in money market funds.

Before things heat up

Now is the time for a spring awakening for cash investors – before money market reforms officially take effect and before the Fed raises rates again. Awareness of cash allocations is critical to successful investing because of the structural transitions underway; cash is therefore moving from an afterthought to a structural allocation, not just for companies but for individual investors as well.

Jerome M. Schneider is PIMCO's head of short-term portfolio management

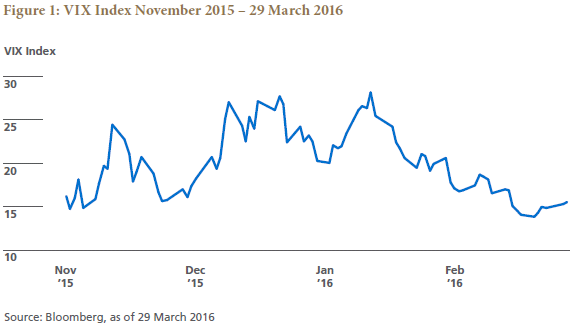

To help stem the effects of market gyrations since mid-2015, many investors have scaled back allocations to “risk” segments – including emerging markets, high yield bonds and equities – as implied and actual volatility have edged higher during the many times of market stress, especially since the start of 2016 (Figure 1).

Seeking traditional “safe harbors” for their cash, U.S. investors are typically turning to a familiar standby: 2a-7 money market funds. Ironically, however, this harbor may not be as “safe” as it once was: Regulatory reforms are taking effect soon, including the requirement for liquidity gates or redemption fees on many funds during times of market stress, which means these vehicles no longer offer pure liquidity management. In a world of structurally low yields, amid rising interest rates and potentially higher inflation, they are also unlikely to offer attractive compensation that can help protect investors’ purchasing power. The increased volatility in the market has already left some investors with negative returns due to increased credit risk.

How then can investors add some stability, or ballast, to their portfolios? Cash allocations can still serve to damp portfolio volatility, but to preserve capital and maintain liquidity, investors may want to consider alternatives to traditional cash vehicles.

The changing landscape

1. Independent credit and interest rate expertise are essential.

Over the past seven years, quantitative easing (QE), zero interest rate policies (ZIRP) and a generally positive credit cycle meant that investors did not have to think much about cash: Stimulative monetary policy minimized interest rate risk, and the likelihood of credit default was unusually subdued during the long economic expansion in the U.S. Today, credit risk is increasing as the credit cycle advances. In recent months, we have already seen credit risk increase in the energy and mining sectors, and many investors – including some in the short-term space – did not properly evaluate these credits. Going forward, independent credit expertise will be essential to preserving capital when investing.

It is also important for investors to recognize that there will be some volatility at the front end of the yield curve as market expectations of Federal Reserve rate hikes under- or overshoot actual Fed moves. Such volatility increases the probability of investor miscalculation and can potentially lead to negative absolute returns just when investors may need access to their cash. While several factors could prolong the pace of rate increases, the direction remains clear, in our view, and once the Fed is convinced it needs to react to firming economic data in the U.S., the front end of the yield curve will be susceptible to re-pricing and the potential for capital loss, which makes expertise in navigating rate rises crucial.

2. Relatively attractive interest rate policy (RAIRP) in the U.S. is creating more demand in U.S. markets.

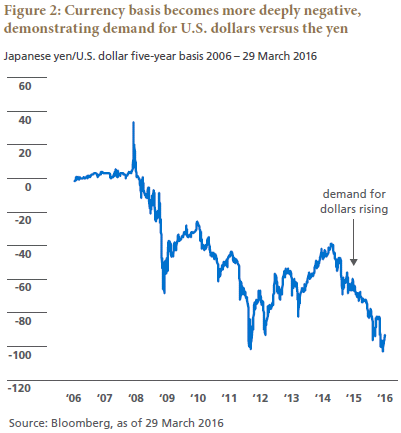

Investors in Japan and the eurozone will likely search more aggressively for return and income following the recent actions by the Bank of Japan (BOJ), which introduced negative deposit rates in late January, and the European Central Bank (ECB), which lowered deposit rates further into negative territory in early March. For investors in these jurisdictions, capital preservation is becoming a daunting prospect; already, many money market funds in Japan have closed because they cannot adapt to the emerging negative rate structure.

These investors have begun to search for investments abroad where they can still find positive interest rates, such as in the U.S. Several real-time indicators show this growing demand from non-U.S. investors. The foreign exchange basis swaps market, for example, reflects rising demand for U.S. dollars versus a variety of currencies. More specifically, Figure 2 shows the increase in demand in recent months from investors looking to buy U.S. dollars versus the yen. We see opportunities for capital appreciation in short-term securities as a result of this growing structural demand, and U.S. investors could potentially benefit by being positioned well, especially within the front end of the credit sector.

The long-expected implementation of reforms in the U.S. for regulated 2a-7 money market funds in the third quarter of 2016 will be noteworthy, but for different reasons than many investors might think. Investors need to be aware of the changes themselves, as well as some of their knock-on effects.

Potential redemption gates and fees. Not only will prime (credit) money market funds no longer be valued at $1 par NAV (i.e., NAVs will float), but also, many will be subject to potential gates and fees during times of stress. For many investors, the guarantee of liquidity without a punitive cost is no longer assured.

Structurally low yields. Unlike previous economic cycles when higher interest rates were reflected in similar increases in the net yields of money market funds, this time around net yields will likely lag the reset to higher rates for a trio of reasons: a limited supply of investible money market assets, administrative fund fees no longer being waived, and recent regulations that have increased demand for money market instruments to meet liquidity and central clearing requirements. While net yields on money market funds should eventually increase with future rate hikes, they may underperform other front-end assets and strategies that do not face the same rigid parameters.

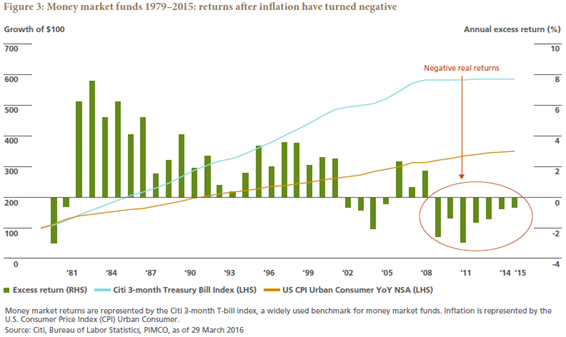

Purchasing power eroding. For much of the past 40 years, money market fund investors benefited from handsome nominal returns. For most of that period, those returns, as measured by a widely used fund benchmark, were higher than the rate of inflation (see Figure 3). However, achieving attractive positive returns, in nominal or real terms, will be extremely challenging after the reforms are implemented later this year.

We are seeing some investors begin to evaluate alternatives to traditional cash vehicles and adjust their strategic allocations to include short-term strategies that have more flexibility to manage credit, interest rate and liquidity risks. Actively managed short-term strategies can invest outside of the money market sphere and diversify across high quality asset classes globally in a way that not only aims to increase returns via varied sources of income, but also adds the freedom and flexibility to better manage liquidity, albeit for an additional step out in the risk spectrum. Asset managers with significant experience and long track records in short-term investing have weathered different economic cycles and can manage portfolios in an effort to benefit from larger macroeconomic trends. They can also offer several solutions to meet investors’ various objectives.

As many investors revisit their cash allocations in the face of market volatility, this is an opportunity to consider capital preservation strategies that are multifaceted in approach and global in scope in order to successfully navigate the changing cash landscape.

Spring Awakening

April 14, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment