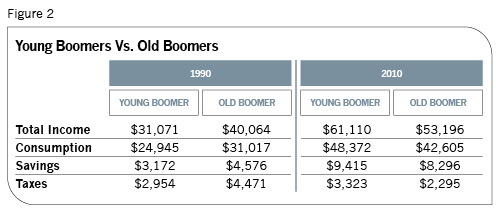

Similarly, in 1990, old boomers were consuming about 77% of their income, saving 11.5% and paying 11.5% in taxes. By 2010, this group had actually increased their consumption to 80%, while their savings were at 15.5% and their taxes at 4.5%. Increasing proportional consumption over savings during very, very financially troubled times is very curious behavior indeed. Obviously, this group of old boomers is totally clueless about what lies ahead after retirement. They seem to have little or no understanding about the funds required to maintain their lifestyles in retirement. Furthermore, the proportion of taxes paid by young boomers were halved between 1990 and 2010 while old boomers' taxes went from 11.5% of income to just over 4%. This tax trend was not limited to boomers. Across the nation, taxes fell from an average of 9.4% to just 4% between 1990 and 2010.

It is heartening to note such a reduction-which champions the market economy. (It also shows clearly the distinction between marginal and average tax rates for laypeople, which might help a presidential hopeful like Mitt Romney explain the major tax contribution of a 15% tax rate.) But from an advisor's standpoint, this is disconcerting news.

Even two-income families are woefully unready. Consider the current realities for income securities: The risk-free benchmark rate for 10-year Treasurys is hovering around 2% while the 30-year benchmark is around 3%. Under these conditions, if we assume boomers cannot afford to take speculative risks with their retirement funds, a return of 3% on $400,000 would give back about $12,000 in risk-free earnings. Compare this to the $39,000 boomers would actually need to maintain their lifestyles in retirement (with an 80% replacement ratio of their current income) and the problem becomes crystal clear. A risk-free retirement portfolio would only be covering about 30% of their lifestyle needs! Could people really pare down their expenses by 70%? How much worse would it be if we explored single-income families?

It's infeasible to solve the problem by seeking a higher rate of return from our investments. Large-cap stocks are currently expected to return about 7% to 8%. Even this high rate leaves an income shortfall of about 20%, and meanwhile, investors in these securities face greater risk. Given that the S&P 500's volatility is about 30% higher than it was in the decade before 2008, a family of two with just $400,000 in savings cannot afford to take any chances. In fact, under these conditions, average boomers should conserve and stretch this meager principal as best they can.

There seems to be no way out except one. For prudent advisors whose clients are not all in the high-net-worth category (we will address this group's issues later), the only alternative is to start changing the clients' current lifestyles significantly and helping them save every last penny they can find. Furthermore, they need to invest these savings in a very prudent way, their main objective being principal conservation. One way is to seek out lower-risk fixed-income type cash flows, perhaps in deferred and fixed annuities. These cash inflows can then be matched with future critical outflows for health care and other basic (non-discretionary) living costs. It is the advisor's fiduciary responsibility to ensure that the future cash flows are not spent on discretionary expenses. Those advisors who can guide unsuspecting average boomer citizens out of harm's way are worth their weight in gold.

Advisors must also watch a client's consumption patterns as he or she slips into retirement. Typically, as family sizes shrink and retirees age, their consumption declines in most categories: Expenditures on food, housing, transportation, entertainment, etc. all go down along with income, savings and taxes. The only category that continues to rise, sharply, is health-care expenses. For example, young boomers spent about 4% on health care in 1990. This grew to 7% in 2010. Similarly, for old boomers proportional health-care spending rose from 4.5% to 9% in the same period. In 2010, people over 65 years of age were spending about 13% of their total income on health care; the figure for those over 75 or more is significantly larger. Given that health care is inflating at rates of 6% or more and given the likelihood that boomers will be consuming more health-care services, it's clear that advisors and their retiree clients need to spend considerable time and effort to plan for these critical expenses. In 2010, the other three big-ticket items for those over 65 were housing (35%), transportation (14%) and food (12%). These expenses total nearly 80% of all retirement spending, and a major portion of them should be considered as non-discretionary.

The High-Net-Worth Boomer Market: Product Shangri-la

The average income in 2010 for all Americans (using a 50-year-old boomer as a reference point) was about $62,500 gross and about $60,700 net of taxes. Approximately 70% of all households in the U.S. earn less than $70,000 per year. On the other end of the spectrum, only 7% of the U.S. population earns more than $150,000 per year. The middle-income groups (those with between $70,000 and $150,000 in income) account for the rest. It is hard for an advisor not to concentrate on the two top groups. But it's also obviously not fair if those in the lowest income categories cannot be served. Those clients need help too, and the commercial advisory companies serving them need to offer strict advice about discipline in their spending habits.

But let's examine the differences in spending habits between the middle class and the economic elite. Those in the high-net-worth group spend about 11% of their annual income on food while those in the middle-income group spend about 12%. Each group spends only about half these amounts for food they consume at home. Both groups spend about $32,000 on housing. Transportation accounts for about 16% of the middle-income group's expenses and 13% of the high-net-worth group's. Finally, the middle-class spend about 7% on health care while the wealthy spend 4.5%.

The middle class also spend proportionately more on each of these categories as their incomes decrease to $70,000 and the reverse when their incomes tend higher toward $150,000. The proportional spending patterns in different expense categories are fairly linear across all income groups. (The spending patterns of boomers and their retirement product needs will be discussed in a future column.)