When jean-marie eveillard retired in 2004 from the First Eagle Global fund, it looked like the party was over. The legendary value investor had built one of the strongest track records in the mutual fund business and the odds seemed low that a successor could keep the winning streak alive. Some investors might have been scared off by the departure of this star manager. But at least one stakeholder, Jonathan Satovsky, chief executive of the New York-based wealth management firm Satovsky Asset Management, kept the faith. The First Eagle team and the investment process, Satovsky reasoned, were up to the challenge of carrying on after Eveillard.

Staying put turned out to be a pretty good call. The First Eagle Global Fund, which Eveillard piloted to benchmark-beating results over nearly three decades, continued to perform competitively, if not spectacularly, in the first two full calendar years after its famous manager left.

But Satovsky came to a different conclusion last year when another fund he invested in saw its star manager head for the exit. Robert Gardiner, a Wasatch Funds manager with an impressive run of picking microcap stocks, decided to start his own shop, Grandeur Peak Global Advisors. This time, Satovsky decided to move assets to Gardiner's new firm, which rolled out mutual funds late last year. It's too soon to judge the success of Gardiner's second act, or the impact on the Wasatch funds he left behind. But Satovsky's analysis persuaded him to follow the manager. "I have no problem with Wasatch," he says, "but I really like the story with Robert Gardiner."

Why the difference? On the surface, there was a fair amount of common ground between the two managers. Both Eveillard and Gardiner enjoyed wide respect for their investing skills when they chose to leave their funds. But Eveillard was not the only person at First Eagle. There was a discipline and philosophy in place at the fund that transcended one man, Satovsky says. He stayed as a vote of confidence for Eveillard's team. But Gardiner, by contrast, took enough of his team with him that he persuaded Satovsky to follow.

Egression Analysis

There are no hard and fast rules for evaluating management changes, simply because every situation is different and the future's always unclear. Yet there are some basic questions to start with, Satovsky says. Investors must ask themselves why they bought a fund in the first place. Were they hooked by the investment philosophy? The discipline and structure of the fund company? Or were they captivated by the manager? If they invested mainly because of the name, and that person leaves, it's time to bolt.

Star managers certainly resonate with the investing public, but as a steward of client assets Satovsky favors a more holistic approach for selecting funds. "I've been more compelled by the process and philosophy around risk management characteristics that the underlying [fund] company exhibits-characteristics that become ingrained in management's culture," he says. If that culture walks out the door, as it seemingly did with Gardiner, an investor may reasonably follow or, if the manager isn't launching a new fund, simply pull the money out.

Before investors even put the first dollar in a fund, they should consider the ramifications if the manager leaves. When I asked financial planners and investment analysts for advice on how to analyze a fund manager's exit, almost everyone emphasized advance planning.

"Before it ever happens in the first place, we talk to funds about their succession plan," says Jim Holtzman of Legend Financial Advisors.

It's impossible to make pre-emptive decisions, but thinking through the process is time well spent. Statistically speaking, one of the funds you own or recommend will lose its manager in the not-so-distant future, Morningstar data suggests.

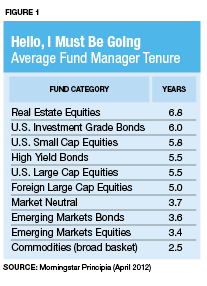

The average manager tenure at mutual funds generally runs three to seven years, depending on the category (see Figure 1). Real estate portfolio managers, for instance, tend to stick around for longer stretches. By contrast, the average tenure at a commodities fund is less than three years, a relatively brief affair.

There's little fallout when managers leave an index fund, of course, because they have little if any discretion over the strategies. In fact, the manager may be close to irrelevant for a well-run index portfolio. But the stakes are much higher with actively managed portfolios.

All Together Now

When a fund is piloted exclusively (or even primarily) by one person, a change at the helm may require reinventing the strategy. Some managers' methodologies are so idiosyncratic that they're difficult, if not impossible, to replicate. A famous example is Peter Lynch, who exited Fidelity Magellan in 1990 after an extraordinary 13-year run of stock picking. His strategy was a widely celebrated triumph in the mutual fund industry, but one that was hard to pin down, inspiring some to label him the "chameleon." Not surprisingly, Magellan's successors have struggled to match his record. It's debatable whether the fund's rocky post-Lynch era in the past two decades is a reflection of bloated assets or the loss of Lynch's golden touch. Perhaps a bit of both. In any case, the fund's investment style within the large-cap space has evolved since he stepped down, and not always in shareholders' favor.

To minimize the risk when their managers leave (and keep clients from migrating, too), investment companies have become fond of teams. More than 70% of U.S. equity mutual funds were team-managed in 2010, up from roughly one-third in 1992 (according to an April 2012 working paper, To Group or Not to Group? Evidence from Mutual Funds, by McGill University's Saurin Patel and Sergei Sarkissian). The rising preference for team-managed strategies may be linked to Morningstar's ranking of portfolios according to style-small-cap versus large-cap equities, for instance. More advisors and investors are opting for greater control over asset allocation by selecting funds that track specific style betas.

Those trends spell waning tolerance for opportunistic strategies run by managers free to migrate across investment styles at a whim. Team products, such as those at American Funds or Primecap Management, where multiple managers each run a small portion of a fund's assets, show more consistency and stability, says Russ Kinnel, Morningstar's director of mutual fund research.

Whatever the motivation, the shift toward team-managed funds has implications for risk and return. Some researchers say team-managed funds are less likely to pursue extreme investment strategies than portfolios headed (or dominated) by one manager. In that case, it's reasonable to expect that single-manager funds are more likely to exhibit relatively extreme behavior. In fact, that's the message in one recent study of equity mutual funds (Is a Team Different From The Sum Of Its Parts? Evidence From Mutual Fund Managers, by Michaela Bar, Alexander Kempf and Stefan Ruenzi in the Review of Finance, April 2011). The authors have discovered that single managers tend to show up in the top or bottom of performance rankings (see Figure 2). And team-managed strategies are more likely to show up in the middle of performance percentiles.

Single-manager funds may not be a growth industry, but tenure is still a relevant factor if you're choosing portfolios under the influence of one name. A 1996 analysis in the Financial Services Review by Joseph Golec noted that "the most significant predictor of performance is the length of time a manager has managed his or her fund." A paper by Qiang Bu in the Journal of Index Investing reaffirms the point, concluding that "experience matters in improving fund performance, especially when the market is volatile." (Bu's paper is called, "Exposing Management Characteristics in Mutual Fund Performance," Spring 2012).

Details, Details...

If manager tenure is still connected with performance, it's only natural to ask: What influences tenure? One variable is corporate culture. Morningstar's Kinnel recently ranked the largest fund companies based on average manager tenure and retention rate, measuring the percentage of managers who have remained at their firms over the past five years. Kinnel says investors should think twice about investing in funds run by companies with low retention scores. "If those who know the company best are fleeing, you probably should not be buying," he wrote last year.

Among the largest firms, Kinnel ranks Dodge & Cox as the top fund company for manager tenure (using data through December 2011), while American Funds ranked first on manager retention last year. Both companies were also number one in these categories in 2010. (For a copy of the rankings, see "Quantitative Rankings of the Largest Fund Companies," January 12, 2012, at Morningstar.com.)

Corporate culture should also be a factor when investors weigh the pros and cons of a manager's departure. It's reasonable to assume that a lead manager's exit from a team-handled fund will be less disruptive than if he were leaving a fund he dominates. But generalities have limits. Ultimately, an investor has to assess the manager or team that's taking over.

That task is no different from choosing active managers generally. But there are extra twists and turns in the cases of talent turnover. The first question an investor must ask (and answer) is: Why is the manager leaving? If he is sick or dying, that's self-explanatory, but if he's retiring or taking another job or if he has been fired, it demands closer inspection. Was he really retiring? Did she really just want to step off the fast track to write a novel? Was he forced into retirement because he was losing his touch? If his performance had started to deteriorate, the news shouldn't come as a surprise. Fading glory is hard to hide when investors are continuously monitoring a fund.

Sometimes a company's internal conflicts spill out into the open and force quick choices. When Trust Company of the West fired Jeffrey Gundlach in December 2009, shareholders of his highly rated TCW Total Return Bond fund were pressed to consider the potential fallout.

Gundlach's track record was impressive, right up to the point that he was "relieved of his duties," so the departure didn't appear to be about wilting performance. TCW confirmed as much when it complained that its star manager had plans to leave, and so abruptly terminated him. The company's explanation was that Gundlach was cut loose because it was looking at "strategic alternatives," including a sale to a private equity firm. Gundlach had a different perspective, and the entire matter ended up in court. In the meantime, he quickly launched a new firm, DoubleLine, along with several TCW colleagues, and was running a new fund by spring 2010.

The challenge for investors in the interim was to determine whether Gundlach's departure had dealt TCW's fund a debilitating blow or only posed a bump in the road. The stakes were high, considering that Gundlach had become a darling in the world of bond funds by virtue of his remarkable track record. TCW partly blunted the impact when it purchased Metropolitan West (a deal it announced at the time of his firing) and shifted management responsibilities for most of the TCW Total Return Bond fund's assets to Tad Rivelle, who was also a celebrated fixed-income manager. Ironically, there were persistent reports that the team that TCW brought in from Metropolitan West has been negotiating its own buyout from parent Societe Generale, this time with TCW's participation. The rumors proved accurate in early August, when TCW was sold to the Carlyle Group.

A bit more than a week after Gundlach was cut loose, Morningstar advised "sitting tight" with Rivelle. The counsel fell on many investors' deaf ears and the TCW fund lost a substantial chunk of its assets. The portfolio subsequently bounced back and has since delivered respectable results. But critics note that the DoubleLine Total Return fund's performance in the first full year of its existence, 9.6% according to Morningstar Principia, outdistanced the TCW fund's 6.1% through April 2012. TCW has not quieted these critics by continuing to tout the long-term performance of its fund when Gundlach ran the portfolio.

Was Gundlach's triumphant second act preordained? No, though his track record hinted that there was more than luck in his record. Tipping the scales in his favor was the large portion of his TCW research and trading team that followed him to DoubleLine. Predicting success (or failure) in active management may be a fool's errand generally, but if you were impressed by Gundlach at TCW, it was fair to expect that his team could deliver comparable results once they'd moved on.

Back To The Fundamentals

Everything is obvious in hindsight, of course. Developing confidence in real time is something else. The arrival of a new manager may be a blessing or a curse, and figuring out which requires some digging. Your analysis may be relatively easy if a big name takes over a fund. By contrast, you'll have your work cut out for you if you're unfamiliar with the new boss. Financial regulations don't make your task any easier-a fund manager's previous record, if there is one, is off limits for publication by a fund company.

You can (and should) investigate the new kid on the block, and that starts with the paper trail, assuming you can find it. But evaluating the impact of a manager change goes beyond looking in the rearview mirror. There's no substitute for qualitative research, says Jack Chee, a senior research analyst at Litman Gregory Asset Management, an investment advisory firm in Larkspur, Calif.

"We want to understand why the manager left. Answering that question could speak to his motivation," Chee says. "On the positive side, the manager could feel that he was getting stretched too thin and asked to run too many products. On the negative side, it could be a purely financial motivation and he wants more of the star mentality."

On the topic of where a manager's going (if he's headed to a new or existing fund), there are basic questions to resolve, Chee continues. "Is his or her team going to follow them? Why or why not? Will there be issues at the new firm that will prevent the manager from focusing on investing? Will they have sufficient assets so that we don't have to worry about the viability of the firm?" A gifted money manager walks out of the door every night with all his intellectual assets. But does he have sufficient resources-compliance, research, trading, marketing departments-to replicate the former glory?

It can take time to answer these questions, Chee notes. "You have to understand the success of a fund in the first place." He recalls that researchers at his firm last year spent a total of nearly 40 hours in conversations with the BBH Core Select fund's management before investing.

Manager changes are a big deal for some advisors, but Rick Rodgers, the founder of Rodgers & Associates in Lancaster, Pa., prefers to let the fund's numbers do most of the talking. Funds that trail their peer groups are eventually given the boot.

A manager change may or may not push a fund off his buy list, but a personnel adjustment alone isn't a reason to flee, he says. "Who's to say that all the changes won't be fabulous?" Rogers muses. "There's no way to know that in advance. We'll only get rid of it if it meets our sell criteria."

Change Can Be Good (Sometimes)

Actually, there's some evidence that struggling funds can improve when a new manager takes over. In September 2001, Ajay Khorana wrote in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis that dismissing poorly performing managers could lead to substantial improvements in a fund's performance.

The future, of course, has a habit of surprising us, and it's impossible to anticipate performance. And there might also be other factors in an investor's decision to leave with the manager. Sometimes the tax implications of leaving are more important. Selling a fund and triggering a hefty capital gains tax may be unwise, regardless of whether you have misgivings about a new manager. Taking into account the tax adjustments, it might be less costly to keep the fund.

If you stay with a fund after the manager leaves, pay extra close attention to risk and return in the portfolio under the new regime. Fund companies may say they're not going to change the strategy, but sometimes they break their promise, Kinnel says.

Don't forget that you're in control. There's always the fail-safe choice: sell. The liquidity of these funds offers an escape hatch if the reasons for staying put aren't persuasive, says Michael Kitces, director of research at Pinnacle Advisory Group. "If there was a magic button that showed me everyone who will earn 100 basis points of alpha, we wouldn't be having this conversation," he says. On the other hand, "it's not like you're signing up for five years." These aren't hedge funds. There are no lockup periods or transparency issues with mutual funds and ETFs.

"The people who really spend a great deal of time investing in active managers tend to have a pretty good clue about their active managers," says Kitces.