When jean-marie eveillard retired in 2004 from the First Eagle Global fund, it looked like the party was over. The legendary value investor had built one of the strongest track records in the mutual fund business and the odds seemed low that a successor could keep the winning streak alive. Some investors might have been scared off by the departure of this star manager. But at least one stakeholder, Jonathan Satovsky, chief executive of the New York-based wealth management firm Satovsky Asset Management, kept the faith. The First Eagle team and the investment process, Satovsky reasoned, were up to the challenge of carrying on after Eveillard.

Staying put turned out to be a pretty good call. The First Eagle Global Fund, which Eveillard piloted to benchmark-beating results over nearly three decades, continued to perform competitively, if not spectacularly, in the first two full calendar years after its famous manager left.

But Satovsky came to a different conclusion last year when another fund he invested in saw its star manager head for the exit. Robert Gardiner, a Wasatch Funds manager with an impressive run of picking microcap stocks, decided to start his own shop, Grandeur Peak Global Advisors. This time, Satovsky decided to move assets to Gardiner's new firm, which rolled out mutual funds late last year. It's too soon to judge the success of Gardiner's second act, or the impact on the Wasatch funds he left behind. But Satovsky's analysis persuaded him to follow the manager. "I have no problem with Wasatch," he says, "but I really like the story with Robert Gardiner."

Why the difference? On the surface, there was a fair amount of common ground between the two managers. Both Eveillard and Gardiner enjoyed wide respect for their investing skills when they chose to leave their funds. But Eveillard was not the only person at First Eagle. There was a discipline and philosophy in place at the fund that transcended one man, Satovsky says. He stayed as a vote of confidence for Eveillard's team. But Gardiner, by contrast, took enough of his team with him that he persuaded Satovsky to follow.

Egression Analysis

There are no hard and fast rules for evaluating management changes, simply because every situation is different and the future's always unclear. Yet there are some basic questions to start with, Satovsky says. Investors must ask themselves why they bought a fund in the first place. Were they hooked by the investment philosophy? The discipline and structure of the fund company? Or were they captivated by the manager? If they invested mainly because of the name, and that person leaves, it's time to bolt.

Star managers certainly resonate with the investing public, but as a steward of client assets Satovsky favors a more holistic approach for selecting funds. "I've been more compelled by the process and philosophy around risk management characteristics that the underlying [fund] company exhibits-characteristics that become ingrained in management's culture," he says. If that culture walks out the door, as it seemingly did with Gardiner, an investor may reasonably follow or, if the manager isn't launching a new fund, simply pull the money out.

Before investors even put the first dollar in a fund, they should consider the ramifications if the manager leaves. When I asked financial planners and investment analysts for advice on how to analyze a fund manager's exit, almost everyone emphasized advance planning.

"Before it ever happens in the first place, we talk to funds about their succession plan," says Jim Holtzman of Legend Financial Advisors.

It's impossible to make pre-emptive decisions, but thinking through the process is time well spent. Statistically speaking, one of the funds you own or recommend will lose its manager in the not-so-distant future, Morningstar data suggests.

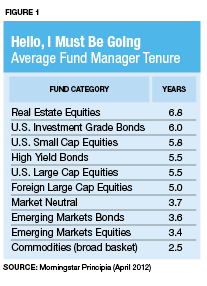

The average manager tenure at mutual funds generally runs three to seven years, depending on the category (see Figure 1). Real estate portfolio managers, for instance, tend to stick around for longer stretches. By contrast, the average tenure at a commodities fund is less than three years, a relatively brief affair.

There's little fallout when managers leave an index fund, of course, because they have little if any discretion over the strategies. In fact, the manager may be close to irrelevant for a well-run index portfolio. But the stakes are much higher with actively managed portfolios.

All Together Now

When a fund is piloted exclusively (or even primarily) by one person, a change at the helm may require reinventing the strategy. Some managers' methodologies are so idiosyncratic that they're difficult, if not impossible, to replicate. A famous example is Peter Lynch, who exited Fidelity Magellan in 1990 after an extraordinary 13-year run of stock picking. His strategy was a widely celebrated triumph in the mutual fund industry, but one that was hard to pin down, inspiring some to label him the "chameleon." Not surprisingly, Magellan's successors have struggled to match his record. It's debatable whether the fund's rocky post-Lynch era in the past two decades is a reflection of bloated assets or the loss of Lynch's golden touch. Perhaps a bit of both. In any case, the fund's investment style within the large-cap space has evolved since he stepped down, and not always in shareholders' favor.