“Buy low, sell high.”

“Buy low, sell high.”

That old investment adage sounds simple enough. But what do you do when there isn’t any “low” to buy? Buy high and hope to sell higher? And what exactly is “low” anyway? A reasonable definition of “low” could be when the price of an investment is lower than its value. But how can we be sure what value is?

Sometimes it’s easy in retrospect to see that things were great values: the painting bought for a couple of dollars at a yard sale that turns out to be an undiscovered masterpiece, for example.

If value is simply cost, then the painting was worth exactly what it sold for at the yard sale – as well as the bonanza price it fetched later at the art auction. How can this be true? It was the same piece of canvas, the same paint, the same frame. Its intrinsic value was the same. The difference in price must be explained by differing assessments of its esthetic appeal or historical significance – its subjective value – to a different set of buyers and sellers.

Similarly, stocks and bonds carry a mix of intrinsic and subjective value. A common stock represents ownership of a piece (share) of a business. A corporate bond is a piece of a loan made to a business. The company’s intrinsic value, like the canvas and paint of an artwork, may include equipment, inventory, and other assets – its liquidation value. This is what bond holders would be left with to divvy up with other creditors if the business failed.

If a business is successful, its value as an operating company is likely to be more than just its intrinsic value. Using good business practices, it may be able capitalize on its resources and the talents and efforts of its workforce to generate more income than it needs to pay its debts, including payments to bondholders, leaving it with profits that can be distributed to its owners – the shareholders – or reinvested to further grow the company. Estimating the value today of those possible future profits is subjective, of course, since the future brings with it all sorts of unknowns that could be good or bad for the company. Still, with some reasonable estimates and a little math, an approximate current value of a company shouldn’t be too hard to agree on.

For the most part, the value of a company should not be expected to change too much from day to day. Unless a factory burns down or is swallowed by a sinkhole, the plant and equipment part of a company’s value shouldn’t change much from one day to the next. Changes in business conditions for a company or the economy as a whole can certainly influence the assumptions used to estimate the subjective part of a company’s valuation. Still, in many cases the magnitude of changes in expectations don’t seem to fully explain short-term swings in stock prices. When it comes to the day-to-day movement in stock prices something else seems to be going on – something closer to estimating the value of art than estimating the value of paint and canvas.

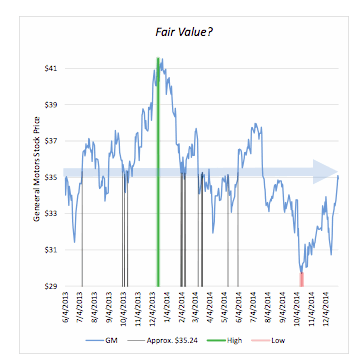

On June 4, 2013, the common stock of General Motors Company (GM) closed at a price of $34.96 per share. On December 31, 2014, GM closed at $34.91. The difference of $0.05 per share represents a change in stock’s value of about -0.14%. With a market value of approximately $54 billion, this is a difference of just over $77 million in the assumed value of the company. Is that a reasonable change in value a company this large over the period of about a year and a half?

Perhaps.

Perhaps.

But what did GM’s stock price do over those 399 trading days on the way to that 5 cent price change?

While the average closing price of GM’s stock over that period was $35.24, the price it traded at from day-to-day swung wildly around that average. Its closing high during that time was $41.53 on 12/17/2013, and its closing low was $29.69 on 10/15/2014 – a range of $11.84! That’s a quite bit more than the nickel difference it ended up with. The stock closed within 10 cents of its average price only 14 times over those 399 trading days. More than 96% of the time it traded at some other price outside that range, and the span between high and low amounted to 33.6% of the average price over the period. (See the accompanying chart.)

How can there possibly be that much confusion about the day to day value of a massive company like GM? Did auto sales soar and dive during that time so dramatically that a fluctuation of more than $15 billion in the value of the company was warranted – only to have the company’s stock end up indicating nearly the same value it had at the start of the period?

Very unlikely.

What seems far more likely is that the price of a stock at any given moment is at best a rough estimate of a company’s value, determined to a great extent by subjective – and emotional – investor reactions to changing conditions and current events. The history of stock investing is full of examples of panics and manias fed by prophecies of doom, exuberant dreams of glory, and convictions about the status quo that eventually turned out to seriously miss the mark. Our goal is to take emotion out of the investment process as much as possible. We believe in using data rather than intuition, process rather than crowd opinion, investing in value when we can find it, and conserving capital when we can’t.

The stock of a great company can be a terrible purchase if the asking price is too high, and a seemingly cheap stock can be just as bad if the company’s prospects are poor. There may always be some disconnect between the value of a company and what people are prepared to pay for a share of its stock. As value investors entrusted with the management of our client’s capital, however, our challenge is to uncover not only attractive companies, but companies whose stock is available at what we believe is an attractive price. After all, the “stock market” is a market of stocks, not companies. On any given day some stocks are likely to be too cheap and some too expensive.

It’s said that differences in opinion are what make markets: a seller’s junk can be a buyer’s treasure. By sticking with a disciplined security selection process, we think we’re far less likely to pay auction house prices for a yard sale stock. The way we see it, finding real value can be a beautiful thing.

Gary E. Stroik, CFP is vice president and chief investment officer of WBI Investments, Inc., which manages $3 billion for individuals and advisors. He can be reached through www.wbiinvestments.com or [email protected]

The Eye Of The Beholder

February 5, 2015

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment