As 2016 began and 2015 ended, global financial markets faced plenty of uncertainty in the wake of the first rate hike by the Federal Reserve (Fed) in nearly nine years. Although the rate hike was well anticipated and priced in by many market participants, the Fed’s move forced markets to focus on imbalances in the global economy and financial markets that had been simmering for years. The fears about how (and when, if ever) those imbalances would be resolved led to an extreme bout of financial market volatility over the first few months of 2016. Those imbalances included:

· The strong U.S. dollar

· A global oil glut and the financial stresses on countries and companies affected by the drop in oil prices

· The slowdown in the Chinese economy, and fears of a “hard landing” as it transitions from an export-led manufacturing economy to a consumer-led domestically focused economy

· Central banks outside the Fed pursuing easier monetary policy via negative interest rates and additional quantitative easing

· Rising fears of widespread global deflation and recession

UNTANGLING IMBALANCES: FED PLAN

At the center of these issues was the Fed’s plan—set out in the December 2015 Summary of Economic Projections—to raise rates four times (by a total of 100 basis points) in 2016.

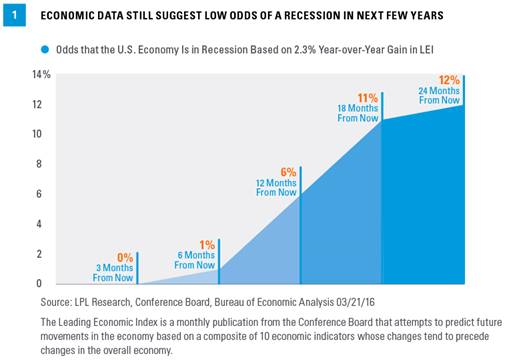

The Fed’s plan to follow up its 25 basis point (0.25%) rate hike in December 2015 with four additional hikes this year didn’t cause the global imbalances noted above, as those built up over the more than eight years of zero interest rates, quantitative easing, slow global economic growth, etc. However, the prospect of the global economy and financial markets successfully working through those imbalances while the Fed was raising rates at that promised pace seemed too much for many asset classes to bear in the first six weeks of 2016. The seemingly intractable imbalances only added to the financial stresses; by mid-February 2016, the S&P 500 was down 10.5% year to date and 14.2% from its May 2015 peak, spreads on high-yield debt to Treasuries widened out considerably, and the price of oil hovered in the mid-$20s per barrel (down more than 30% from the start of 2016 and 75% from mid-2014 peaks). By that time, financial markets were pricing in near 100% odds of a recession occurring this year. Here at LPL Research, we placed the odds of a recession at 25–30% (up from 10–15% at the start of the year), with most of the increase due to the increased likelihood of a policy mistake here or abroad. The economic data itself, based on the Leading Economic Indicators (LEI), still only suggest only a 10–15% chance of a recession in the next few years [Figure 1].

UNTANGLING IMBALANCES: GLOBAL VIEW

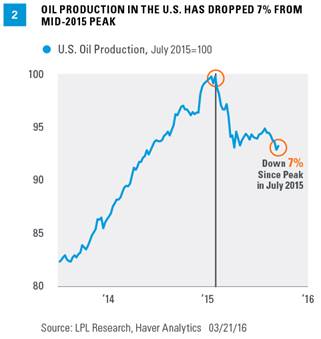

Prior to the Fed’s meeting last week (March 15–16, 2016), a few of the aforementioned imbalances were slowly beginning to resolve, albeit ever so slowly. By mid-February 2016, at the peak of the market’s concerns over the imbalances, oil production in the lower 48 United States had dropped by 7% from its mid-2015 peak [Figure 2] in response to the 75% drop in oil prices, and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) agreed, in principle, to a “freeze” in production. If sustained, the ongoing reduction in supply in the U.S. and the freeze in OPEC production may help to reduce the global oil glut, stabilize oil prices, and relieve (perhaps even reverse) some of the financial stresses put on corporate balances sheets, financial markets, and emerging market currencies and current account balances. OPEC has scheduled a meeting for April 2016 to assess the freeze and discuss if an actual cut in production is warranted.

Some clarity on the economic slowdown and transition in China in late February and early March 2016 also helped to untangle some of the imbalances. After making a series of policy missteps in the summer and fall of 2015 with its currency and equity markets, Chinese authorities have sounded more rational and in control in recent weeks, sending markets soothing signals that it won’t abruptly devalue its currency and will continue to do whatever it takes to hit its lowered targets for economic growth in 2016. Despite the recent progress, however, Chinese policymakers have plenty of work to do, and China still has many issues to contend with (property price bubble, bad loans in its banking system, lack of transparency, etc.). But at least for now, the market seems to be satisfied that Chinese authorities are saying (and doing) the right things to avoid a “hard landing” in China.

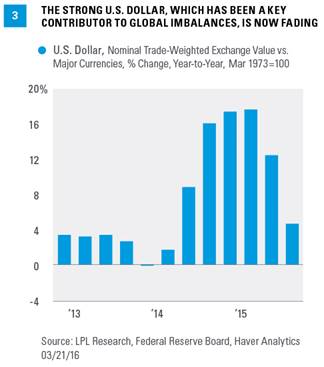

The relentless strength of the dollar was also a key contributor to global imbalances [Figure 3]. The strong dollar was putting unwanted stress on emerging market currencies, economies, and current account balances; at the same time, it was hurting global commodity prices, driving U.S. inflation lower, and hurting U.S. exports, corporate profits, and the manufacturing sector. Here again, these effects of the strong dollar were not caused by the Fed’s actions at its December 2015 meeting, but rather by the divergence between U.S. and global economies and monetary policies that was exacerbating problems many years in the making. Although not entirely of its own making, the key to resolving this issue was squarely on the Fed.

At last week’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, the Fed acted boldly. Citing “global economic and financial developments of recent months,” the FOMC said last week that it now plans just two 25 basis point rate hikes this year (instead of four) and that its long-run neutral fed funds rates is now 3.25%, 25 basis points lower than Fed projections in December 2015. Those two shifts—fewer rate hikes this year and a lower end point for the fed funds rate in the years to come—went a long way toward further resolving the imbalances that wreaked havoc on global markets at the start of 2016.

COST OF RESOLUTION?

However, the Fed’s decision to help resolve some of the global imbalances may come at a cost, if financial markets and, perhaps more importantly, U.S. consumers begin to see an unwanted uptick in inflation in the coming months. In our view, the data already show that the labor market has tightened enough to cause some wage inflation, although Fed Chair Yellen said she has yet to see a convincing pickup despite plenty of anecdotal evidence of wage pressures. Readings on inflation, most notably inflation excluding food and energy (also known as core inflation), are also moving higher, especially in the service sector; but here again, in her post-FOMC meeting press conference, Fed Chair Yellen downplayed that rise, noting that some of the recent rise in inflation readings are “transitory.”

Thus, although the Fed’s actions at its March 15–16, 2016 FOMC meeting may have relieved some of the global imbalances and provided some additional time for the oil market glut to clear, for global growth to stabilize, for China to rebalance its economy, and for some of the financial stresses to ebb, it may have done so at the cost of higher inflation (and more aggressive rate hikes) later this year or in 2017.

John Canally is chief economic strategist for LPL Financial.