Much ink and many pixels have been spilled over the past few years about the rise of the gig economy, sharing economy, on-demand economy, 1099 economy, freelancer economy or whatever you prefer to call it. Some of the claims about its growth have been overstated, and I’ve written several columns trying to debunk them, or at least put them in context.

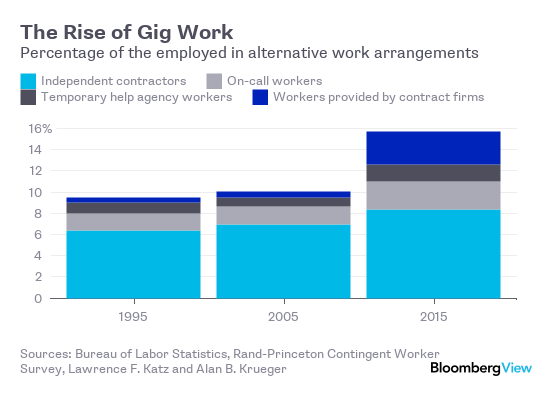

But this data, from economists Lawrence F. Katz and Alan B. Krueger’s new paper on “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States, 1995-2015,” is for real:

After barely changing between 1995 and 2005, the share of U.S. workers in alternative work arrangements jumped from 10.1 percent in 2005 to 15.8 percent in 2015. That’s a pretty big leap. As Katz and Krueger write, “All of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements.”

These arrangements for the most part did not involve work arranged through online gig-economy platforms -- only about 0.5 percent of workers “identify customers through an online intermediary,” Katz and Krueger found. They do speculate that “technological changes that lead to enhanced monitoring, standardize job tasks and make information on worker reputation more widely available” have helped bring about the rise in alternative work. Other possible causes that they cite include shifts in the age and education characteristics of the workforce (more on that in a moment), the Affordable Care Act (which generally makes it easier for independent workers to get health insurance), corporate efforts to boost profits by contracting out more work and the lingering effects of the Great Recession.

The Katz-Krueger survey was designed to be compatible with an earlier data series from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which asked workers about contingent and alternative work arrangements in 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001 and 2005, before stopping for lack of funding. In January, Labor Secretary Tom Perez announced that the survey will be conducted again in May 2017, but Katz and Krueger had already conducted a smaller version as part of the Rand American Life Panel last October and November.

The differences between Katz's and Krueger's 15.8 percent finding and the higher percentages reported in some other recent surveys mainly have to do with definitions. The Government Accountability Office’s April 2015 estimate that 40.4 percent of U.S. workers were in alternative work arrangements included part-time workers as well as some self-employed workers not covered under the BLS's definition of alternative work. It was also based on a survey conducted in 2010, when the percentage of involuntary part-time workers was still quite elevated in the wake of the recession. The 2015 Freelancing in America survey that deemed 34 percent of U.S. workers to be freelancers included moonlighters who already had other jobs, as well as some small-business owners with employees.

These different ways of counting aren’t wrong -- moonlighters, for example, seem to be a big factor in the online gig economy, and Katz and Krueger miss them by only counting people whose main job involves alternative work arrangements. Katz and Krueger do that, though, to allow for comparison with past BLS surveys -- and that comparability is informative.

It reveals, for instance, that workers ages 55 to 75 and workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher have always (since 1995, at least) been more likely than others to be in alternative work arrangements. As a result, rising education levels and the aging of the population account for part of the overall growth in alternative work. But the share of older and better-educated workers in alternative work arrangements has also continued to rise, at a pace faster than that of the rest of the workforce. Moreover, the 55-plussers are the only age category in the U.S. that has seen its employment-to-population ratio rise over the past two decades.

What this may mean is that the growth of the gig economy, at least the growth measured by Katz and Krueger, is being driven not so much by struggling millennials lining up gigs online as by 60-year-olds working as independent contractors. What’s not clear is whether they’re doing this because they’re semi-retired and value freedom and flexibility, or because they’ve been downsized out of a full-time, full-benefit job and have to settle for contract work. Sometimes the gig economy empowers, sometimes it oppresses. But at least we now know that it really is growing.