Lower Interest Rates

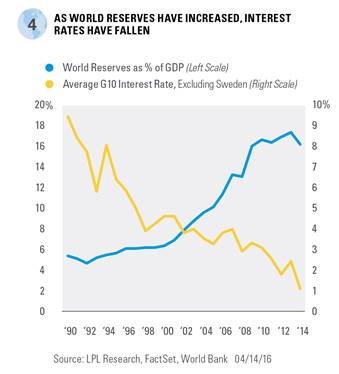

One of the largest impacts of the global savings glut is falling, or low, interest rates. Countries generally don’t seek to make money on their foreign reserves, and therefore, they invest in perceived safe-haven securities that can help preserve their buying power, such as Treasuries and high-quality sovereign debt of other developed nations, or gold. However, as the demand for savings has grown over time, it has led to more competition for the limited supply of high-quality sovereign debt. In 2014, world reserves totaled more than $77 trillion, while the supply of Treasuries was only $39 trillion. Figure 4 shows how the increase in world reserves compares against the average interest rate for a 10-year bond for G10 countries (minus Sweden, which didn’t have data available prior to 2005).

Deflation

Inflation is often referred to as too much money chasing too few goods; but in a world with a savings glut, the opposite is true, leading to the potential for deflation. All else equal, higher savings lead to weaker aggregate demand and consequently, downward price pressures to attract new demand. Central banks across the world have been working to avoid this outcome, placing interest rates near, or even below, the zero bound, and also using quantitative easing (QE) to spur demand for risk assets such as stocks. However, even with this extraordinary monetary stimulus, inflation rates have remained stubbornly low, and are still below central bank targets in many areas of the world, including the U.S., Europe, and Japan. These consistently low inflation rates suggest that other factors, such as a savings glut, are helping to maintain downward pressure on prices.

Lower Stock Market Returns

Sub-par investment and slower economic growth means weaker earnings growth, a primary driver of stock prices. Business capital spending has been weak during the current recovery, as companies funneled cash raised from increased borrowing into share buybacks rather than investing into their businesses. Buybacks may help boost returns in the short run by spreading the same amount of earnings over fewer shares, but aren’t likely to boost long-term earnings power. So while stock markets may still manage positive returns, the savings glut likely diminishes their potential.

When Will The Glut End

Though the contributors are changing, the global savings glut is not likely to disappear soon, and few solutions are on the near-term horizon. One driving factor is that deficits are widely viewed as negative, while surpluses, which actually cause much of the problem, are seen as positive. This encourages countries to follow policies that encourage surpluses, such as attempting to weaken currencies to boost exports.

The upcoming retirement wave in developed countries will help, but individuals, for a number of reasons, are working longer in life than prior generations. Eventually late-career workers will transition to spenders, but this is likely several years away and will postpone any meaningful decline in the savings glut.

Another way that developed countries can help reduce the glut over time is to improve the ratio of older to younger workers. Loosening restrictions on immigration, especially for highly skilled workers, is a near-term solution, while improving incentives for having children may help in the longer term.