Let's say a family patriarch calls your wealth management firm one day, interested in having you manage his $45 million account. When you meet, he seems like a strong, dynamic entrepreneur who you'd love to work with. Distant alarm bells go off in your head when he casually mentions his family has some complex issues, but you ignore them. You're more focused on the account and the revenues it will create. After agreeing to a fee schedule, you happily seal the deal.

As you get to know the client, however, you discover he disdains his entire family, especially his older son, who has not found his way in life and is a serious over-spender. The client is on his third wife and there are significant tensions between her and all three of his grown children. He has not shared his estate plan with anyone in the family. At 79, he is adamant about never giving up control over his wealth. You have no idea what the other members of his family want from their inheritances. Yet they will be your clients if something happens to the patriarch.

Are any of these concerns for you? Or do you expect to act purely as a fiduciary for the money, not the people involved with it? How will these issues impact how you make decisions and how the family views your service to them?

The bottom line is that this wealthy patriarch-who appeared to be a prize when he first walked through the door-is likely a high-maintenance client whose family will place a lot of demands on you and your staff. This family's issues may be so complex, in fact, that you may not have even taken them as clients if you had known about them from the start.

The lesson here for advisors is that situations like this are indeed avoidable. By assessing a family's dynamics early in the recruitment process, and measuring a family's complexity level, advisors may be able to surmise whether they're entering into a relationship with Cliff Huxtable of The Cosby Show or the incorrigible Tony Soprano.

The Importance Of Assessing Family Complexity

By making an accurate upfront assessment of client families, advisors can avoid mistakes when it comes to allocating resources, assigning a relationship manager and keeping client relationships profitable. It makes for a relationship that is more likely to lead to success than failure or, at worst, litigation.

What follows is a practical approach that advisors to high-net-worth and ultra-high-net worth clients can use to differentiate between families that function well even in crisis (i.e., The Cosby Show) and families so dysfunctional they are never out of crisis (i.e., The Sopranos).

In Figure 1, we offer a conceptual model that organizes wealth management services along two dimensions: one that defines the financial complexity of wealth management services and another that defines the complexity of the client's personal and family dynamics.

When the complexity of the dynamics is low, advisors can focus primarily on services. But when personal and family dynamics increase in complexity, it trumps anything on the services side. Thus, skillful management of family dynamics improves the delivery of legal, tax, trust and financial services.

The "Two-Axis Model" naturally leads to a division of labor. A key question is who should be primarily responsible for managing client situations arrayed along the personal/family dynamics axis. For straightforward client situations without many psychological issues, the front-line relationship manager (also called the senior client advisor or family wealth advisor) should carry the ball. Wealth management firms should be able to provide a spectrum of services and experts to supplement the relationship manager's role, matching family complexity with increasingly specialized expert consultation. Services can be in-house or on referral. This avoids situations where relationship managers are expected to cope with highly complex family dynamics far beyond their skill level or where they stick to what they know but leave clients floundering when it comes to family dynamics issues.

Factors In Family Complexity

The concept of wealth complexity units has emerged as a way to accurately anticipate the service needs of families and to determine a pricing model most likely to assure profitability. Going beyond basics such as account size, wealth complexity units are a function of factors such as the number of trusts, financial entities, family branch members, global and domestic residences and international holdings. These factors are essentially units along the financial dimension of the Two-Axis Model. As the number of wealth complexity units goes up, families are ranked higher in financial complexity.

Two families with $45 million in assets-even with similar wealth complexity units-can have completely different service needs depending on the frequency and emotional intensity of their phone calls, the tenor of their quarterly meetings and the demands for services beyond the account agreement. These family complexity units determine service planning, service delivery, staff resource allocation, pricing and profitability-perhaps even more strongly than wealth complexity units. We suggest that six key factors may contribute strongly to the level of family dynamics complexity:

Level of conflict: Ranking at the top is the degree to which conflict is present in a family. This includes how long the conflict has existed, how deeply it impacts the family and whether it constantly lurks beneath the surface. When a family member is openly hostile or contemptuous of others you should be alert to the issues that lie beneath (note that the issues are often not what family members say they are). Moreover, when there is conflict to a pernicious degree, advisors are never spared.

Conflict by itself is not necessarily dangerous, but a natural and sometimes necessary part of life and family. Advisors, however, need to recognize the nature of the conflict. Conflict that is situational, appropriate to the issues and managed through respectful communication is quite natural. In contrast, some family conflicts constitute a state of war that is endured over generations. The key is whether the parties are able to openly share their differences and make the effort to resolve them.

Communication style: Open, active and reasonably transparent communication within a family bodes well-not only for how they treat each other, but also for how they will treat you. When good communication is present, complexity is lower.

Complexity rises when families attempt to smooth over even reasonable conflict for the sake of "family harmony."

Unfortunately, this communication style leaves issues unresolved. Heavily stifled communication-common in wealthy families-means the family will be vulnerable to even normal stresses. Communication is especially important when there are significant differences across generations, and when the younger generation feels ignored. Lack of openness makes it difficult to resolve issues and leads to the advisor getting caught in the middle. That's why advisors should be wary when dealing with secretive families that punish or suppress those who attempt to be open or act in a disparaging way toward other family members.

Level of fairness: Healthy families have a basic sense of justice in their dealings with each other and advisors. They balance conflicting needs and value fairness over competition. They believe in weighing decisions carefully rather than expeditiously. With this approach, families can avoid rifts or serious jealousies and cultivate an atmosphere of trust and cooperation. This contrasts with families that-possibly because of events in the family history-have differing views on what constitutes fairness. A lack of shared governance and a history of inequitable decisions may teach family members that they are likely to be treated unfairly. They therefore feel they must fight for what they want or defend themselves from others.

Governance and decision-making: Most client families are headed by a first-generation entrepreneur who makes most if not all of the decisions regarding wealth management and other issues. If the decision-maker at least solicits opinions and listens to other family members, particularly those in the next generation, this can work reasonably well. Families with more collaborative and distributed decision-making tend to handle stresses as they occur rather than let things fester or escalate.

These families typically employ effective formalized structures, policies and activities to arrive at decisions, such as family councils, governance policies and regular meetings.

When decision-making is highly rigid, completely centralized or highly splintered, and actively resistant to input from other family members, family complexity units go way up. Poor governance and decision-making provoke conflict, create a sense of injustice, shut down communication and destroy trust. When dealing with issues such as succession planning, the family is likely to experience significant stress, increased conflict and increased demands for service.

Presence of addictions: Alcoholism, drug abuse, over-spending and other types of addictive behavior add to family complexity. Unfortunately, it's not unusual for affluent families to have these issues. This is especially serious when the family avoids facing the addiction problem, even when some discussion is necessary for good planning or implementation of services. It is also more difficult for advisors when multiple members of a family have addiction problems.

Families with addictions often share a variety of characteristics that are problematic. They are often highly rigid, harbor multiple secrets, deal poorly with conflict, exhibit black-and-white/all-or-nothing thinking and communicate poorly about even the normal stresses of life. They care more about keeping their addictions a secret than solving the problem. Addictions, therefore, can serve as a marker indicating the family may have other negative characteristics that drive up family complexity.

Situational Factors: The factors listed so far represent family characteristics that can deeply and broadly impact complexity. Superimposed on these are the many stresses of life that can worsen family functioning on a situational basis, but which you as an advisor may have to contend with. Resilient families tend to weather stressful situations relatively well, whereas dysfunctional families may splinter and deteriorate. Stresses include when people enter or leave a family. New in-laws, for example, can force a family to make decisions about how it will handle outside people coming into the family. Other examples include medical crises such as cancer or mental disorders such as dementia or bipolar disorder. If the leader of a family suffers a death, or is physically or mentally incapacitated, it can destabilize a family, increasing family complexity.

Green For Go, Yellow For Caution, Red For...?

Using a traffic signal analogy (Figure 2), first suggested by colleagues Keith Whitaker and Susan Massenzio of Larkmeadow LLC, the levels of family complexity can be separated into three categories, corresponding to green, yellow and red lights. At the beginning of a client engagement and at annual reviews, you may want to place checkmarks in each column about where you see the client. A quick glance will alert you to clients well into the higher levels of personal or family complexity, compared to those clients you evaluate as less complex or difficult.

The characteristics and recommendations about each zone are as follows:

Green zone clients are those wonderful, easy-to-work-with clients who benefit from advice, collaborate with advisors, communicate reasonably as a family and work toward their individual and common goals. These client families are most likely to benefit from your work and are often considered "low-maintenance" clients who manage stress and are resilient. Enjoy them and be glad you have them. You can also use them for training new advisors in preparation for working with more difficult clients requiring greater skill.

Yellow zone clients are those who struggle with their wealth and families, but who you can work with under most circumstances. It's important to learn about their family dynamics, to be aware of their strengths and weaknesses, their methods of communication and governance, and their vulnerabilities. Make sure to assign advisors who have the skill to serve these types of clients. Be careful of your pricing for yellow zone clients since their demands for service can escalate without warning.

Red zone clients are in the small but high-maintenance group that is most difficult to work with and who take the largest toll on your firm. You know you have a red zone client when the source of the referral apologizes to you for introducing you to the client. These clients have many of the markers of severe family complexity: high conflict, poor communication, a history of rifts or major fights within or outside the family, overly rigid or splintered decision-making, addictions and chronic crises. As one family-office executive put it, "When it's client X on the caller ID, I just want to let it go to voicemail. Otherwise, I have to gear myself up to take the call."

What can you do if you have a red zone client? First, protect yourself and your staff from burnout. If possible, assign them to an advisor who works well with problem clients. Even then, keep expectations low. Provide emotional and logistical support to that advisor to maximize the chances of success and to reduce stress rippling through the advisory team. Second, try to price the engagement realistically for the likely service demands. Few things are more aggravating than providing lots of service to a difficult, demanding, unappreciative client, knowing you priced the engagement too low to get them in the door. Prepare to have ongoing fee discussions that match fees to service demands as best you can, or accept that the client may take his business elsewhere (with apologies to the next wealth manager in line). Set limits with red zone clients either on service demands or fees, or you will live to regret your "flexibility" on the account.

Finding The Right Match

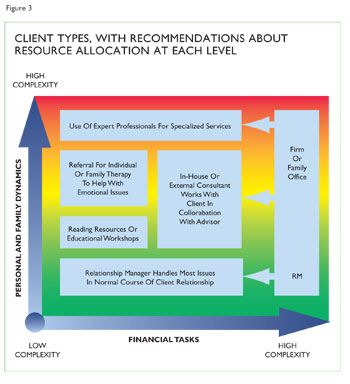

Many missteps in wealth management are the result of mismatches between the needs of the family and the approach taken by the wealth manager. Make sure your services and skills are consistent with the level your clients need due to their family complexity. Figure 3 shows a method of allocating resources to green, yellow, and red zone clients.

Monitor yellow zone clients closely and bring in outside consultants if the situation demands it. With at-risk clients, it's important to know when to call upon family dynamics experts, mental health professionals or other specialists. Other consultants who may be useful for serving this clientele include financially trained therapists, family business consultants and family wealth counselors. Yellow zone clients can turn into red zone clients if you are not careful or if you underestimate their complexity.

Recognizing when you need outside help is even more imperative with red zone clients. Red zone clients need highly expert consultation by both advisors and outside professionals. However, don't assume the entrenched red zone client will respond to even highly skilled family dynamics consultants. Clients deep in the red zone can be impervious to the best efforts of experienced professionals, leaving in their wake fired consultants and failed referrals. Finally, know when it's time to simply end the relationship. The goal, after all, is to embrace the Huxtables among your clientele, and weed out the Sopranos.

James Grubman, PhD ([email protected]), is a psychologist and consultant to families of wealth, their advisors, and other resources in the financial services industry. His practice, FamilyWealth Consulting (www.jamesgrubman.com), is based in western Massachusetts.

Dennis T. Jaffe, PhD ([email protected] and www.dennisjaffe.com), is professor of organizational systems and psychology at Saybrook University in San Francisco, and an advisor to families about family business, governance, wealth and philanthropy.