This presidential election has driven home a problem that others have been noticing the last few years: The U.S. seems to be out of ideas for economic growth. The main argument appears to be over redistribution -- tax rates, the size of the welfare state, free college. Protectionism is also making a comeback; Bernie Sanders would restrict trade and punish Wall Street, while Republican candidates would curb immigration. These are mostly debates about the size of the pie. But what about growing it?

Most ideas for growth still endorse some form of neoliberalism -- a catch-all term that advocates free-market policies and deregulation. Free marketers tend to assume that slashing regulation will boost growth, possibly by dramatic amounts, despite only mixed evidence on the matter. On the left, “third way” proponents continue to emphasize targeted deregulations, such as a reduction in occupation licensing, weakened intellectual-property protections, a reduction in land-use restrictions, and increased immigration. I tend to agree with the latter, but neoliberalism is fundamentally an old idea. We’ve been trying to boost economic freedom for decades now, and there’s a good possibility that all the low-hanging fruit has been picked.

So what else is there? Looking around, I see the glimmer of a new idea forming. I’m tentatively calling it “New Industrialism.” Its sources are varied -- they include liberal think tanks, Silicon Valley thought leaders and various economists. But the central idea is to reform the financial system and government policy to boost business investment.

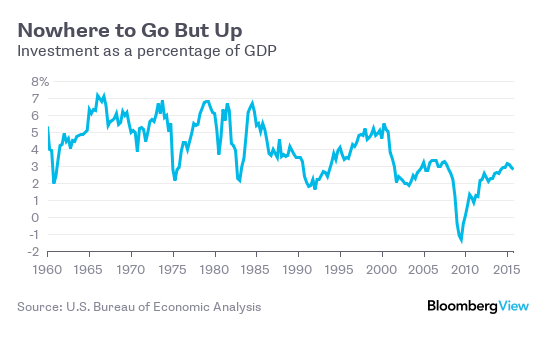

Business investment -- buying equipment, building buildings, training employees, doing research, etc. -- is key to growth. It’s also the most volatile component of the economy, meaning that when investment booms, everything is good. The problem is that we have very little idea of how to get businesses to invest more. Unfortunately, net U.S. business investment has been more or less in decline for decades:

Some people have suggested that the way American businesses make their investment decisions is fundamentally broken. Standard corporate finance teaches us that businesses invest to maximize shareholder value. The people we call “investors” -- lenders and shareholders -- are thought to drive business-investment decisions with their financial-investment decisions. Lending money or buying stock -- financial investment -- is supposedly a vote of confidence in the real investment plans of a business. In fact, our theories assume such a tight connection between financial investment and business investment that we use the same word for both activities.

But what if this system just doesn’t work as well as it should? If financial investors have short-term horizons, they may not push businesses to do the long-term investment that really boosts the economy. J.W. Mason, a researcher at the Roosevelt Institute, found that businesses have recently been borrowing money not to make real investments, but to make cash payouts to shareholders:

In the 1960s and 1970s, an additional dollar of earnings or borrowing was associated with about a 40-cent increase in investment. Since the 1980s, less than 10 cents of each borrowed dollar is invested...Today, there is a strong correlation between shareholder payouts and borrowing that did not exist before the mid-1980s. This change in corporate finance, associated with the “shareholder revolution”, means there is good reason to believe that the real economy benefits less from the easier credit provided by macroeconomic policy than it once did.

This could be happening because investors don’t see much of a future for American businesses, and are thus choosing to get out while the getting is good. On the other hand, it could mean that investors are simply thinking in the short term and are more interested in quick cash grabs than in pushing companies to maximize their long-term value.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley’s titans of industry are starting to complain about the system. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, for example, regularly laments public financial markets' short-term focus. The evidence is on his side: Public companies invest much less than private ones.

If the public markets are broken, how can they be fixed? Intel co-founder Andrew Grove suggests tax incentives for companies to increase their scale. Eric Ries, a startup-management guru, offers a more radical idea: a new stock exchange that would force investors to hold stocks for long periods of time. This so-called Long Term Stock Exchange would be a far more radical step than the tax on financial transactions being suggested by Sanders and others. It would force public companies to choose whether they wanted the liquidity of the normal stock exchanges or the security of knowing that their owners would remain the same from year to year.

Ries’s idea would be a sort of intermediate step between opaque private markets and highly transparent but short-termist public markets. It would take significant regulatory changes to implement, and Wall Street firms would likely be skeptical, if not outright opposed. But it’s a big, bold, fresh idea in a country where such new approaches are few and far between.

When Silicon Valley’s capitalists and researchers at left-leaning East Coast think tanks are roughly in agreement, they may be onto something big. New Industrialism -- the idea of using regulatory, financial and tax policies to push businesses toward greater real investment -- is not yet mainstream, but it could be just the thing we need to fix the holes in our neoliberal growth policy.

Noah Smith is an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University and a freelance writer for a number of finance and business publications.