With social unrest rising in several producing nations, could the next phase of an oil shock be unfolding?

Over the past few months, we have forecast a rebound in oil prices toward $50 per barrel over the course of this year as prices were unsustainably low for the corporate sector to produce the energy required to meet future demand.

A series of supply outages and robust demand have moved prices in line with our expectations, albeit a bit earlier than expected. Although the Canadian wildfires have certainly cut some of the surplus crude oil, we are now paying more attention to the growing instability in key oil-producing countries.

While the failed Doha deal increased bearish concerns over growing OPEC supplies in the medium to distant future, the impact of low prices on many sovereign producers is morphing into something immediately and meaningfully more bullish for prices.

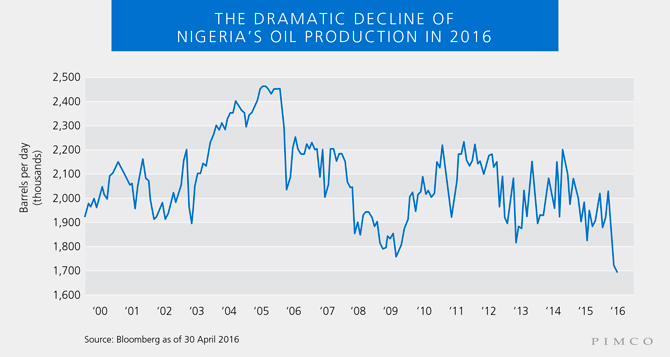

Escalating violence in the Niger Delta, in part due to a lack of funding to buy effective security, has reduced a material amount of good quality oil coming from the Atlantic Basin and dropped Nigerian output to its lowest level in decades (see Figure 1). Current events are reminiscent of the problems Nigeria experienced from late 2005 through 2009, when attacks by MEND (the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta) significantly lowered production capacity; if anything, the most recent violence is operationally more destructive.

In addition, escalating violence and political instability in Iraq and Venezuela, exacerbated by low oil prices putting material strains on government services, have led to modest production losses and threaten future production from two of the largest global oil producers. The timing could not be more challenging for the oil market as production from non-OPEC countries is registering a substantial year-over-year decline.

With corporate balance sheets still in much need of repair, oil-producing companies are limited in how they can respond to recent price increases. This means oil markets likely hinge on the reaction of Saudi Arabia and other pivotal Persian Gulf producers.

If exports and production are not increased, two implications stand out : 1) This could signal limitations on production capacity, which is inherently bullish should another supply shortage occur, and 2) the bearish narrative about Saudi Arabia increasing output to gain market share will be revised (we believe this is long-term risk, not a short-term risk).

In sum, recent events raise concern that the next destabilizing phase of the oil price shock is upon us, one where it is less about credit and more about social stability – or rather, instability.

Greg E. Sharenow is an executive vice president in PIMCO's Newport Beach, Calif., office and a portfolio manager focusing on real assets.