What is the role of the CEO? Many advisors never stop to think about that. They are so busy working with clients, rainmaking and putting out the occasional fire that there's little time to consider what they need to do to lead their businesses.

Textbooks tell us that the CEO plans, coordinates, controls, evaluates and leads the organization. He or she:

Focuses the business

Mobilizes resources to achieve goals

Influences the organization's culture

Ensures efficiency and effectiveness

Grows the firm financially

Protects the entity

Ensures a customer-driven strategy

And so on ...

That's a lot of responsibility. More simply put, the CEO is responsible for where the firm is going and how it is growing. Leading a growing (i.e., thriving) company sounds easier than it is. When so many issues are out of a CEO's control, instead the question should be asked, is thriving even realistic?

Generally speaking, yes-as long as a boss considers a long time frame. A firm may not grow each and every year, but if it isn't thriving over time, it is likely destined to decline.

So how do CEOs at small advisory firms translate their leadership role into action? One way is by thinking strategically about what their companies' contribution to customers is and how it differs from the competition's. CEOs then communicate that vision throughout their organizations, inspiring movement forward.

Make A Plan

To that end, what does the CEO actually do? One of his or her main activities is to oversee the creation of the company's business plan-a key tool for leading-and monitor its implementation. Many advisors say they plan, but few put the plans in writing.

Business plans can enhance corporate memory. Sometimes, we simply forget the way we were thinking in the past. There can be disconnects, as different people remember agreements differently. Moreover, if we don't write down our plan, we tend to start over each year, instead of building off the previous business cycle.

A written plan can also forge discussions that get people committed. This is especially important in larger ensemble organizations, where business planning is typically done by a group. Honest dialogue ferrets out different opinions about the firm's vision or direction.

In daily work, everything seems crucial, but a written plan helps ensure that decisions are put in perspective and priorities are set so that only the critical things are focused on. Sometimes it is worthwhile to forgo one small activity to pursue a truly critical long-term objective-to work on something like converting from commissions to fees or transitioning from investment to wealth management.

The business planning process also promotes more strategic thinking (for instance, allowing team members to assess the firm's "SWOT": strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats). Teams can also create formal criteria to select projects that will have the greatest impact on business. In any case, the planning process is as important as the written plan itself.

For a small business, a written plan need only be two to four pages long if it focuses on where the company is going and how it is growing. The document needs to be both concise and precise.

It's the CEOs job to align the vision, strategic directives and goals to move their companies along their intended path. That means they must create a business vision and strategic directives for their firms over the next three to five years. The goals must be specific and their success measurable; they must also be realistic, with defined deadlines.

Although most advisors find tracking clients' financials as natural as breathing, the instinct does not kick in when it comes to monitoring their own. The business plan also needs to focus on financial projections for the firm.

Among the quantitative, financial components of this plan are the revenue forecast, which includes, at a minimum, a review of client segments, products and fees, and anticipated expenses and budget tracking throughout the year. While all firms should address profit and operating margins, in reality, the larger the firm, the more likely it is to track gross profit and operating profit margins, as well as productivity ratios such as households and household revenue per advisor. Margin and productivity analyses are used to assess the firm and how well it is managed. The sophisticated firm must also identify a formal benchmark it can use to compare itself against companies of similar size.

In the past, financial advisory entrepreneurs didn't require as much business acumen as they will in the future. With the trend toward ensemble organizations, more business models and stronger competition, advisors must make more conscientious decisions about both the quality and the quantity of their business.

For a firm's plan to be useful, it has to be used. A simple formula for putting a business plan into action is to read it every week, to assess the performance on articulated goals every month, to communicate the status to the entire firm every quarter and to pursue the planning process anew every year.

The Corporate Culture

Another job for the CEO-one whose success is hardest to measure-is to create the firm's corporate culture. Though this concept is "touchy-feely" to some people, it cannot be ignored.

Think of words that describe different organizations you've encountered: "professional," "stuffy," "casual," "fun," "flat," "structured," "formal," "laid back." Every firm develops a culture whether or not the CEO plans it, but it is his or her responsibility to harness that culture to help the firm achieve its business plan. Culture is part of the organizational glue, something hard to put into words for employees, but something they contribute to.

Other Roles

CEOs wear other hats, too, especially in smaller firms. They may act as the HR manager, focusing on hiring, job descriptions, performance reviews and employee handbooks. Or they could be operations managers, attending to efficient processes, policies and technology. They could act as marketing managers or as sales managers, motivating, training or tracking advisor activity. While these are important roles that an advisor plays, they are not central to the CEO's job.

Many advisors will declare that they don't have time to be a CEO. In fact, at most small financial advisory firms, the idea of a full-time CEO is ridiculous, since the advisor would only wear the hat some of the time. But how much time is that?

If we acknowledge that creating and using a business plan are essential tasks of the CEO, how much time do they realistically require?

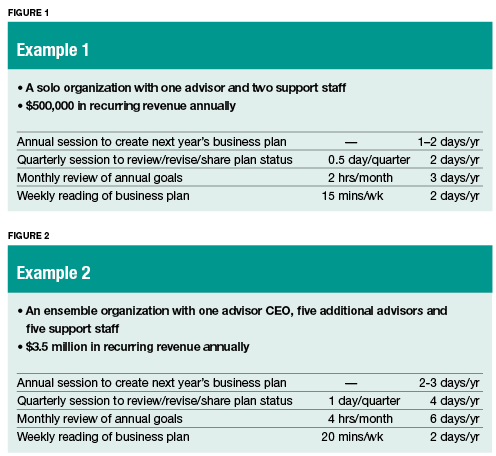

Let's take two hypothetical situations, assuming that the CEO has a 40-hour work week, takes four weeks of vacation per year, two weeks off for training, education and due diligence work, and 10 holidays. That's the equivalent of 44 weeks, or 220 workdays per year. The following are two examples of the time offices of different sizes might spend on business planning and implementation. The math offers insight about the actual time required to be CEO.

If a solo organization with one advisor and two support staff members (see Figure 1) has $500,000 in recurring annual revenue, the advisor could spend one to two days per year on a session to create next year's business plan. The firm could offer a quarterly session to review, revise and share the plan status. This session could last half a day per quarter or two days a year. Meanwhile, a monthly review of annual goals could take two hours per month and three days a year. And a weekly reading of the business plan could take 15 minutes, or two days per year.

Added up, these are eight to nine days per year, or 4% of the advisor's time annually.

In Figure 2, an ensemble organization has one advisor CEO, five additional advisors and five members of the support staff. The firm has $3.5 million in recurring annual revenue.

Here, an annual session to create next year's business plan would take two to three days per year. The quarterly session

to review and revise the plan status could take one day per quarter, or four days a year. The monthly review of annual goals can take four hours per month or six days per year. And a weekly read of the business plan could take 20 minutes, or two days per year.

In this case, that's 14 to 15 days per year, or 6% to 7% of the advisor CEO's time.

Not as much as one would have guessed, correct? Moreover, even though the business plan is not a CEO's only responsibility, it is an activity with a high return on investment for the time spent.

Being Serious About Leadership

A firm that takes the CEO role seriously will consider a formal performance review for the person wearing the hat. Imagine, for example, that the CEO received a performance review every six months-like any other employee of the firm. This would allow the firm to ask if the CEO did the following things:

Created a written business plan document;

Kept the plan top of mind in daily interactions;

Regularly assessed company performance goals defined in the business plan;

Shared the firm's results with others, so that there would be a firmwide vested interest; and

Harnessed the enthusiasm of the entire organization.

More simply, did the CEO create a business plan and then use it weekly, monthly and quarterly to drive the organization?

If you are the CEO, and if you rated your own performance on each question on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 highest, how would you rate yourself? Would you exceed, meet or fall short of expectations? How would your assessment match the assessment of others in your firm?

Giving a CEO a formal performance review at the end of the year may be the jolt that helps a firm begin to take the CEO role seriously. If that sounds unrealistic, it might be time to consider how the CEO role should be filled in your organization. If, for example, you acknowledge that the future of the industry is changing quickly, considering these questions may lead you to contemplate whether the firm might be better off merging with another firm that could assume leadership. Perhaps you would look to your new partners to hire an outsider to fulfill the CEO role.

Regardless of the outcomes of these considerations, the bigger an organization gets-or wants to get-the more critical the need to take the responsibilities of the CEO seriously.