For the past six plus years, ever since the Fed launched QE1 in March 2009, we have lived in an era I’ve described as the Golden Age of the Central Banker, where the dominant explanation for why market events occur as they do has been the Narrative of Central Bank Omnipotence. By that I don’t mean that central bankers are actually omnipotent in their ability to control real economic outcomes (far from it), but that most market participants have internalized a faith that central bankers are responsible for all market outcomes.

As a result, an entire generation of investors (we investors live in dog years) has come of age in a market where fundamental down is up and fundamental up is down. What’s the inevitable market reaction to real world bad news – any bad news, regardless of geography? Why, additional accommodation by the monetary Powers That Be, united in their common cause to inflate financial asset prices through large scale asset purchases, must surely be on the way. Buy, Mortimer, buy! During the Golden Age of the Central Banker, monetary policy is truly a movable feast for investors.

But the Golden Age of the Central Banker has now devolved into the Silver Age of the Central Banker, and monetary policy is no longer the surefire tonic for investors it was even a few months ago. In less poetic terms, the Coordination game that dominated the strategic interactions of central banks from March 2009 to June 2014 is now well and fully replaced by a Prisoner’s Dilemma game in the long run and a game of Chicken in the short run. As a result, monetary policy is now firmly a creature of each nation’s domestic politics, and the Narrative of Central Bank Omnipotence is in turn devolving into a Narrative of Central Bank Competition.

Why the structural change in the Great Game of the 21st century? Because this is what ALWAYS happens during periods of massive global debt, as the existential imperatives of domestic politics eventually come to dominate the logic of international economic cooperation. Because this is what ALWAYS happens when global trade volumes roll over and global growth becomes structurally challenged.

Yes, that’s right, global trade volumes – not just values, but volumes, not just in one geography, but everywhere – peaked in Q3 or Q4 2014 and have been in decline since. That’s pretty much the most important fact I could tell you about this or any other period in global economic history, and yet it’s a fact that I’ve never seen in a WSJ or FT article, never heard mentioned on CNBC.

Using WTO data on seasonally-adjusted quarterly merchandise export volume indices, as of Q3 2015 (the last data point from the WTO), the US is off 1% from peak export volumes, the EU is off 2% (this is EU exports to rest of world, not intra-EU), Japan is off 3%, and China + Hong Kong is off 5%. That’s through Q3. Working from global trade value data, converting to local currencies, and making some educated guesses about price elasticity to estimate Q4 2015 volumes, I’m thinking that the US is now off 3% from peak volumes, the EU is off 2.5%, Japan is off 5%, and China + Hong Kong is off 7%.

Now those numbers probably don’t seem very large to you, and certainly in the Great Recession those numbers got a lot larger (about an 18% peak-to-trough decline in worldwide export volumes from Q2 2008 to Q2 2009). But it’s incredibly rare to see any sort of decline in export volumes, particularly a decline that’s shared by every major economy on Earth. In fact, you don’t get numbers like this unless you’re already in a recession.

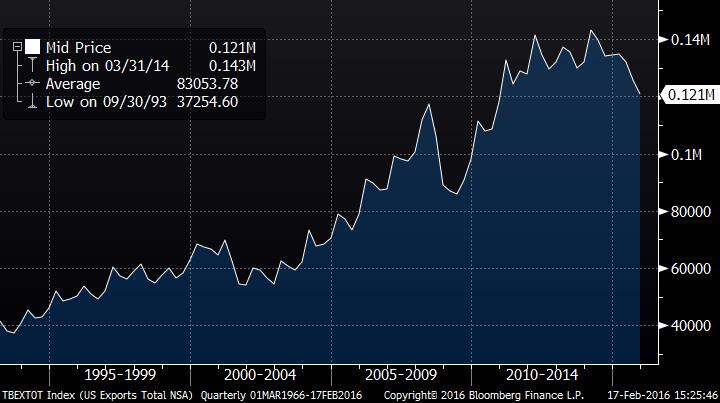

For example, here’s a chart of quarterly US export data since 1993. Now this chart is showing total value of US exports, not volumes of US exports, but you get the idea. Over the past 20+ years, we’ve never had a peak-to-trough decline in exports like we’re seeing today that wasn’t part of a full-blown recession, and we’re getting close to a decline in values (but not in volumes) that rivals what we saw in the Great Recession. The next time someone tells you that there’s a 10% or 20% chance of a recession in the US in 2016, show them this chart. Export growth is THE swing factor in GDP calculations. I don’t care how consumer-driven your economy might be, it is next to impossible for a real economy to expand when your exports are contracting like this. The truth is that we are already in a recession in the US, and this notion that you can somehow divorce the overall US economy from the obvious recession that’s happening in anything related to global trade (industrials, energy, manufacturing, transportation, etc.) just drives me nuts. Yes, it’s a “mild recession” or an “earnings recession” (choose your own qualifier) because the decline in export values (i.e., profits and margins) has only started to show up as a decline in export volumes (i.e., economic activity and jobs). But it’s here. And it’s getting worse.

This is the root of pretty much all macroeconomic evils. If global trade volumes in Asia, the US, and Europe are contracting simultaneously, then global growth is contracting on a structural basis. Global contraction in trade volumes everywhere is exactly as rare as a nationwide decline in US home prices, and it’s exactly as mispriced from a risk perspective. The 2007-2009 nationwide decline in US home prices blew up trillions of dollars in AAA-rated residential mortgage-backed securities. A continued contraction in Asian, US, and European trade volumes will blow up whatever vestiges of monetary policy cooperation remain, and that’s a far bigger deal than US RMBS.

When global trade volumes contract, the domestic political pressure to raise protectionist barriers and seize a larger slice of a smaller trade pie becomes unbearable. That was true in the 1930s when protectionist policies took the form of tariffs and quotas, and it’s true today as protectionist policies take the form of currency devaluation and negative interest rates.