It has been a blockbuster year for longer-dated government bonds. That's not such a great thing.

Source: Bloomberg USD Global Developed Sovereign Bond Index 10+ Year

Source: Bloomberg

U.S. Treasuries coming due in more than 15 years have returned 9.3 percent so far this year, the biggest gain for a similar period since 1986, Bank of America Merrill Lynch index data show. Sovereign debt of developed nations globally has gained an average 9.1 percent this year, compared with losses on stocks and riskier bonds.

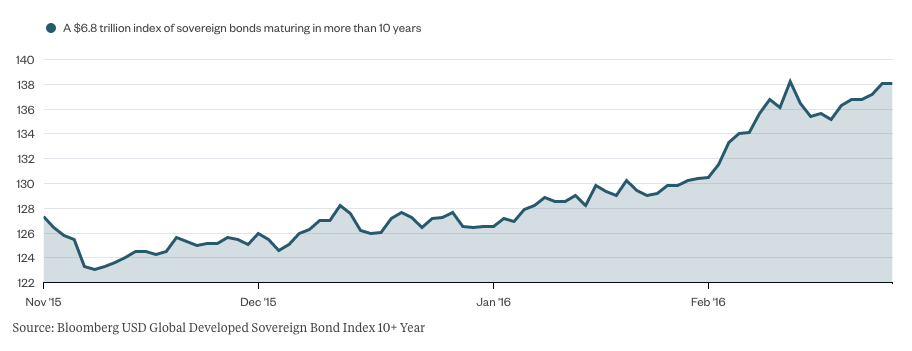

Booming Bonds

The longest-dated government bonds of developed nations have had a huge rally this year.

This is welcome news for investors who plowed into these notes. For the global economy, not so much. It means that investors are so convinced that inflation will remain muted for decades that they're happy locking in low and lower yields for the next 30 years. It's hard to blame them, especially in light of increasingly uninspiring economic forecasts and central bankers' newfound love affair with negative interest rates.The European Central Bank is expected to announce additional stimulus measures in coming weeks, and investors seem to be piling into the region's notes to get ahead of that. Meanwhile, Japan's surprise announcement to charge banks interest to store excess cash reserves has pushed yields in the region to record, logic-defying lows.For example, yields on 40-year Japanese government bonds have dropped below 1 percent. In Germany, 30-year bonds are yielding 0.8 percent. In the U.S., 30-year notes are yielding 2.6 percent, compared with an average 4.7 percent yield over the past two decades.

What Yield?

Investors are accepting less than 1% yields to own 40-year Japanese government bonds.

There's a paradox at the heart of this bond boom that is possibly even more disturbing: On the one hand, central bankers are promising greater economic growth and inflation, which should make these bonds less attractive. On the other, they're pursuing policies that would further lower benchmark borrowing costs, pushing investors into these notes.

This feels like an unsustainable tension. One of two things can happen: Either inflation will pick up, leading European and Japanese central bankers to start talking about abandoning their negative-rate policies and possibly spurring a big selloff in these longer-dated notes. Or else inflation won't pick up, the global economy will slow even more and these bonds will continue to be attractive.

Given some of the recent data out of Europe and Japan, option No. 2 appears more likely. Euro-area consumer prices rose less than initially estimated in January, and the region's inflation appears to be cooling faster than expected. And in Japan, the picture emerging from the negotiations between some of the nation’s biggest companies and their unions is one of stagnation and slim raises, which limits how much inflation can tick up, according to a Bloomberg News article by Keiko Ujikane. The Bank of Japan’s key price gauge didn’t move in January as it continued to hover around zero.

If inflation eventually picks up, then this trade will face an incredibly painful end when a lot of investors try to sell their negative-yielding debt to buy higher income-producing securities. If it doesn't, that means central bankers' tools are ineffective at stimulating their economies. Either way, the lower these yields go, the more fragile the market becomes.

Lisa Abramowicz is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering the debt markets.

The Worst Kind Of 9% Bond Rally

February 26, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment