Of course, Stein cautions us not to read too much into this historical relationship for forecasting. Clearly many other factors are at work. Though Stein does not attempt to describe how those factors work—how the transition from credit cycle to business cycle works—the historical evidence clearly supports the notion that changes in the credit cycle lead the business cycle.

So How Might Changes In The Credit Cycle Lead The Business Cycle?

We have already argued that the spread of commodity risks to the broader credit cycle might result from undermining liquidity as fears of greater default risks in commodity-related securities spread at lower and lower commodity prices.

How might that risk spill over into a broader business cycle risk? Certainly the tightening of credit outside of commodity sectors appears the obvious transmission channel. Yet ample global central bank liquidity might be argued to be more than offsetting. Particularly in the U.S. market, improving access to liquidity for consumers in housing and a greater willingness to use credit for consumption given household balance sheet repair might offset and even dominate any credit concerns from the corporate sector. Certainly given U.S. consumers’ larger role in growth this argument has even greater merit to offset the corporate default and commodity concerns.

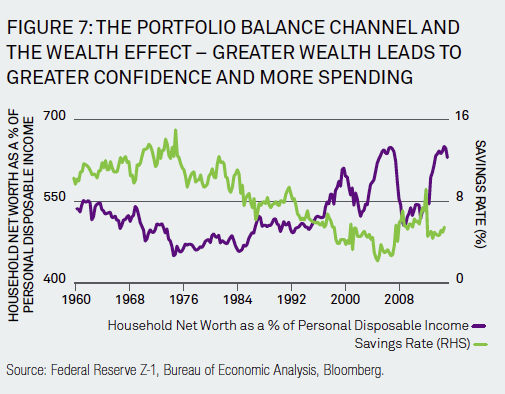

However, the consumer channel itself could be the channel through which the commodity concerns spread. Unique to this cycle, the transmission of monetary policy has relied to a great extent on a novel source, “the portfolio balance channel.” The term—coined by Ben Bernanke—reflects the fact that the Fed has relied on financial market asset inflation to do the transmission of accommodation into stimulus: reflating financial assets reflates confidence and this leads to greater spending. Figure 7

But what works on the way up can fail on the way down. Consider the support for stock prices stemming from corporate buybacks. Those are fueled by debt markets.

Close the debt markets and you close the buybacks. Investors reward management for buying back shares on the way up. On the way down they get punished. Take that support out from underneath the stock market and you remove the only net source of demand for stocks.

Promises, Promises

For completeness, we turn now to the other risk scenario where rather than the deflation risk just described, inflation expectations grow faster than expected. In the case of stabilizing commodity prices, the outlook for headline inflation quickly becomes one of rising inflation. That is merely the artifact of past commodity declines washing out of the data. But the strong payroll creation in U.S. labor markets suggests the potential tightening to the point where wage gains might begin to accelerate. Under such conditions, the market focus might shift from the deflation concerns brought about by China, commodities and credit losses to inflation. Though the Fed promises a “gradual” normalization, that promise is conditional on its economic forecasts turning out to be correct. But the Fed has been a poor forecaster. Two-sided risks to the Fed’s outlook lie in the low likelihood outcome (in our outlook) of faster-than-expected wage growth signaling an even tighter labor market and a need for faster normalization, or the case outlined earlier where oil’s spillover effects halt normalization.