A storm has blown through the American economy in the last two years. Small and growing business owners saw some of the worst damage, and unlike their larger peers, are having more trouble recovering.

As they crawl out of the mess, they have found credit particularly hard to access and their cash flows often strained. There are longer-term financial challenges as well, including their companies' fallen values. The sinking worth of their enterprises stems in part from the lack of credit they can find to finance sales. There are also fewer prospective buyers around, and generally significant value volatility.

Because their business values are hurt, owners also face more difficult retirement and exit plans. Furthermore, if their wealth is tied up in their businesses, they may not be adequately diversified.

Empathy And Reality

Consider what a family does when they're thinking of selling their house. First they fix it up, then time the sale to market. Business owners ought to be thinking the same way, yet they often avoid capital improvements, try to sell when the market is depressed and, worst of all, avoid professional advice.

The key for advisors trying to help business owners get a plan and rebuild is to offer empathy, but also inject reality, and that means helping them focus on the long term. Business owners spend a lifetime working in their business, but rarely spend much time working on it.

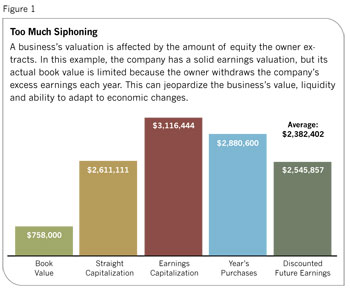

Take the example of equity. Small business owners don't always realize that they have to finance their own buyouts and their own retirements. And it's not clear to them that company equity is the engine driving their ability to retire successfully. An advisor must get the business owner to understand that when he pays himself an excess amount of income each year, he's essentially taking the equity out of the business rather than setting up a reserve to help him when he wants to leave. Figure 1 shows how this practice affects a company's business value. A company may generate ongoing profits and have a solid value as an ongoing business, but the actual book value of the business may be less than expected.

This presents two long-term planning challenges. First, if the business owner sees his business as a source of retirement income, he may lack the liquidity to fund the payments. Second, if he wants to continue the business by selling it internally to family or management, the buyers may lack liquidity to both pay him and keep the business operations going.

Borrowing on that equity by taking it out as excess profits each year essentially takes the fuel from the engine.

Once the advisor helps get this message across, the next step is to move forward with long-term planning. This will likely require transferring excess income into some form of savings. And this essentially means converting excess income into a fund for an exit plan. The nuts and bolts of the conversion depend on the business owner's particular circumstances.

One of the most important things to consider is who the owner will sell to. Will the business go to an outside party or will he transfer it to family or internal management? In the current economic environment, for example, when there are fewer buyers, there is less available loan capital and there are depressed business values, he may need to transfer within the company's own ranks. This likely means either gifting or taking a note. Either way, he will need equity to execute the transfer.

Planning The Future

As he plans for the future, there are some things that should be built into the plan to assure there's equity available for his exit, particularly if he's transferring the business to his key employees:

Any equity designated for a future exit should be just that: designated. This capital must be segregated from operating expenses and should not be readily accessible by the business. Ideally, it should be creditor-protected.

Equity should also provide a source of diversification for the business owner. Whether it is held by the business, by the internal buyers or by the business owner personally, the funds should be diversified and not just part of the general business capital.

Finally, this equity must be available when it is actually needed. Whether the need is triggered by the owner's death, his disability or his retirement, the funding equity for the business transfer must be available as liquid cash, not just marks in the ledger.

The exact exit and retirement plan will vary with the circumstances, but there is a basic set of steps that define the process.

1. The business should be valued. The owner needs to know the true value of the business in order to figure out a value for transfer, to estimate taxes and to calculate the amount of retirement income that will be generated.

2. The transfer plan should be structured and tangible. It may call for a sale (now or in the future), a bonus to key employees, or a gift to family, depending on the owner's goals. Whatever transfer techniques the business owner develops, he must figure out how they will affect cash flow and how the transfer will be funded.

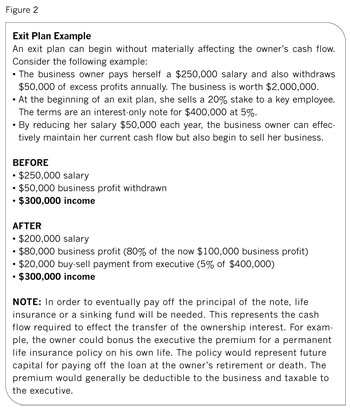

For example, if the plan calls for the owner to start selling part of the business to key managers for a note, the owner should calculate the cash flows during the loan period and at payoff. If he intends to sell 20% of the business to key employees, he should calculate how much he would lose in dividends otherwise payable to himself, and how much he would receive in payments from the buyers. Furthermore, if he uses life insurance to pay off the loan principal, he should include this in the calculation. Figure 2 shows how these cash flows might work in such a plan.

3. The plan must be funded. A plan without funding is just an expensive piece of paper. And, like the exit plan, the funding plan should be tangible and material. For example, to say the plan will be funded with borrowed money in the future is to expose the transaction to the vagaries of the economy and interest rates. Likewise, it's more a wish than a plan for the owner to assume that the estate taxes will be paid with money borrowed from the government after he dies.

Pay Ahead

To the extent possible, the owner should prefund the transaction now. This gives him several advantages. He'll know the terms and conditions of the plan better and he can make them more adaptable to economic changes. Furthermore, it's another way of diversifying assets since company profits go to non-company assets. And one of the best advantages of prefunding is that it compels fiscal discipline. As the owner allocates dollars to the fund, he pays himself first, avoiding the temptation to use retirement dollars for today's expenses.

Prefunding can be done with a corporate sinking fund, with increased allocations to qualified plans, with funds allocated to a rabbi trust or with life insurance. In the last case, consider how prefunding helps create a predictable and manageable exit plan for the owner, since the cash value of life insurance is acquired while the owner is insurable and still working.

If he retires, the tax-deferred accumulated cash values represent a source of retirement income. If he dies prematurely, the death proceeds offer a tax-free source of capital to his beneficiary. Depending on the jurisdiction and the way the life insurance is held, it may also be exempt from the reach of creditors. And, perhaps best of all, the business owner has funded this insurance on a fixed, predictable schedule. Premiums go into the insurance product, offering diversification, tax advantages and prefunding.

There is little question the economy has disrupted the plans of business owners, and the rebuilding process may be long and cumbersome. But advisors can help these owners peer into the future and begin planning for an eventual exit and retirement. Getting a handle on the owner's goals and finances can lead to a well-thought-out and adequately funded long-range plan.

Steve Parrish, JD, CLU, ChFC, RHU, is National Advanced Solutions Consultant with the Principal Financial Group.