A surge in technology stocks over the last year pushed the Nasdaq Composite Index to a 15-year high in July, although this has raised concerns in some corners that the market may be facing another bubble, such as the one experienced during the dotcom frenzy of the 1990s.

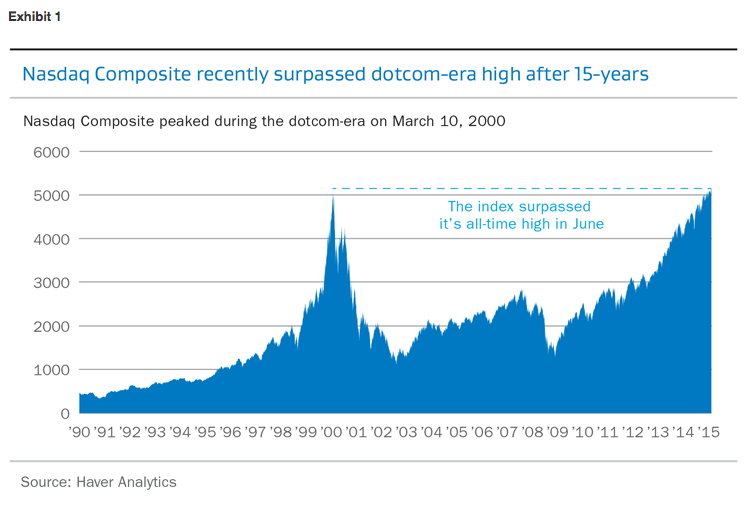

With a 52.3 percent return, the technology-laden Nasdaq outperformed all other major U.S. equity indexes over the 3-year period ended on August 31. By comparison, the S&P 500 increased 37.1 percent and the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 24.2 percent. Nasdaq outperformed these broad indexes over the past 12 months, gaining 3.9 percent as of the end of August, compared to a 3.2 percent decline for Dow Jones and a 1.5 percent drop for the S&P 500. Nasdaq also surpassed its all-time high in July, which was last set 15-years ago—when the dotcom bubble expanded and then popped (see Exhibit 1).

Despite their lofty returns, today’s tech companies are not the second coming of Pets.com, one of the poster-children for the overvalued and overhyped stocks of the 1990s. Share prices and market capitalizations may be rising today, but a number of tech companies are more profitable, many have plenty of cash on hand and valuations that are justified by fundamentals. The industry is also no longer a novelty—technology has entered “middle age,” and now comprises 20 percent of the overall S&P 500 index, the largest sector in the index.

We believe there are many important differences between “then” and “now,” and that tech stocks are anything but monolithic. There are newcomers and legacy companies, and some from each camp offer compelling cases for investment. What’s more, we believe that because of solid fundamentals, today’s tech sector offers both value and growth opportunities, making it an important part of any U.S. equity strategy.

In stark contrast to the late 1990s, tech companies have some of the highest cash positions among all companies in the S&P 500 Index. Some well-known tech companies essentially have become value plays, yielding dividends of 3 percent or more. During the dot-com bubble, valuations often were based on a company’s intangible “potential,” while today valuations are backed by cash flow and cash holdings. Companies are generating actual revenue from real customers.

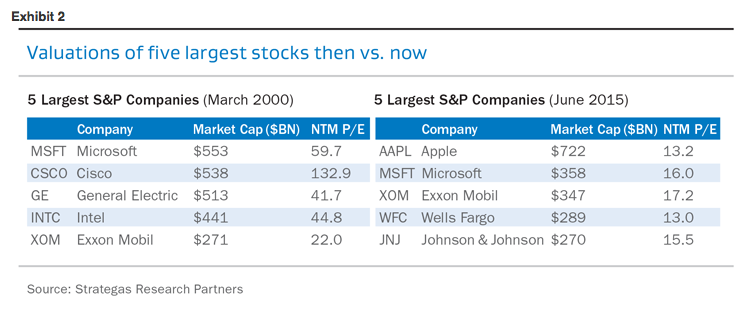

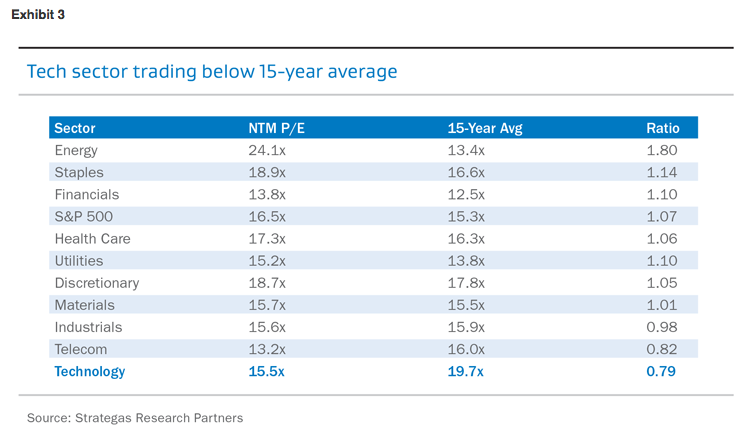

Valuations are far lower and more in line with the overall market today. In 2000, for example, the biggest companies by market value in the S&P 500—Microsoft, Cisco Systems and Intel—had forward multiples of 59.7, 132.9 and 44.8, respectively. As of June 30, the biggest tech companies—Apple and Microsoft—had forward multiples of 13.2 and 16, respectively (see Exhibit 2). The sector as a whole is trading below its 15-year average for forward earnings (see Exhibit 3).

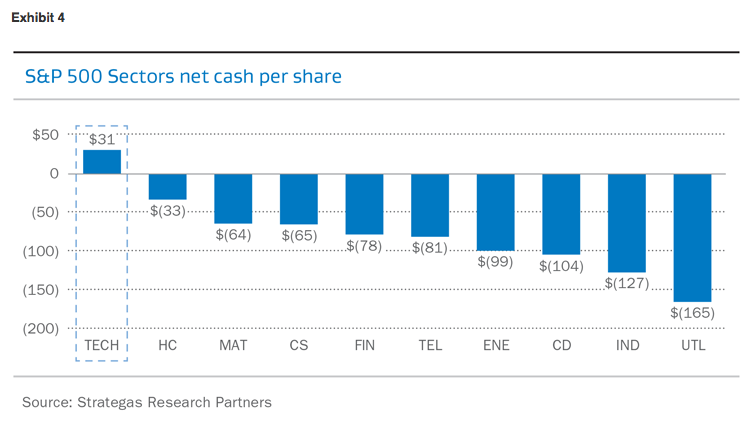

Technology companies, by and large, also have plenty of cash in reserve, and some have initiated or enhanced dividends in recent years. The tech sector as a whole was the only one in the S&P industry groups with positive net cash per share, which means it has capacity to keep paying dividends to investors who are seeking current income and are less concerned with market appreciation. (see Exhibit 4)

Holding Back On IPOs

Rather than racing to the public markets as a primary source of financing, tech companies today are waiting longer to file initial offerings. By the time Facebook went public in May 2012, for example, it was worth $104 billion and had been in business for almost a decade. Other highly valued companies are choosing to stay private and forego the public markets completely.

Investors are more cautious as well. While the “hot” IPO defined the tech market of the late 1990s, public offerings are fewer and less frenzied than they were 15 years ago. Moreover, the proliferation of venture capital and private equity in recent years has given startup companies more access to alternative forms of capital. As a result, there have been far fewer big IPOs that garner widespread attention, as today’s growth companies have a clearer path to profitability. Companies such as Snapchat, Dropbox, Spotify and Pinterest, for example, are planning to go public and are expected to command market values of tens of billions of dollars, far higher and at a much later stage than newcomers in the 1990s.

Across the tech landscape, there are groupings of companies based on valuation, accentuating the split between smaller, high-growth companies and larger, legacy ones. Most of the large-cap legacy companies are trading at 12 to 14 times earnings, while many of the growth companies are trading on revenue multiples because they are growing rapidly and have not generated significant earnings yet. That doesn’t mean they are imitating their 1990s counterparts. Most are cash-flow positive, generating significant revenue—a billion dollars or more—and in many cases, their customers are Fortune 500 companies.

Many of these newer growth companies have 5 percent to 10 percent operating margins, compared with 30 percent to 50 percent for the more established players. Identifying the growth companies that can achieve legacy operating margins amid the shifting dynamics of the marketplace is the challenge for investors.

The Shifting Tech Landscape

Prior to the introduction of tablets and mobile computing, the technology market was largely driven by hardware demand, and PC sales were watched as closely as rig counts are in the oil and gas sector. In the 1990s, Microsoft spurred increased demand for PCs because each generation of its Windows operating system required faster PCs with more memory to run it. In the 2000s, such demands eased, as new PCs leaped far ahead of software specifications, enabling PC owners to keep their machines longer. However, the PC market continued to grow at a healthy annual rate of 10 percent to 15 percent.

The rise of tablets and smartphones, however, began to erode this demand for PCs, and current PC growth is essentially flat on a year-over-year basis. Much of the PC market demand shifted to tablets, but now, even that growth is slowing. Tablet makers are still selling about 200 million units a year, but it’s not clear that those sales will increase, because most customers who planned to switch from PCs to tablets have already done so. Next-generation tablets have, for the most part, represented incremental advances that haven’t convinced customers to replace older models.

Similarly, as recently as a few years ago, the market for mobile phones had a compound annual growth rate of 30 percent to 40 percent. Just as with PCs, though, market penetration has plateaued, leaving less room for growth. Today, the smartphone market is growing at about a 10 percent annual rate. Tech investors are focused on equipment makers who can capture and maintain market share, while smaller companies are getting pushed to the sidelines.

Hardware makers are looking for new ways to help customers stay connected, including via wearable devices such as the Apple Watch. These devices, however, are unlikely to replicate the growth from tablets and smartphones. Massive companies like Apple, which already are confronting the law of large numbers, might struggle to find growth. Instead, maturing tech giants are beginning to return their growing cash stockpiles to investors. Companies that a decade ago refused to consider such measures are now paying dividends.

Technology Migrating To The Cloud

The shift during the past 15 years from hardware to software is now being followed by a more subtle migration from traditional software to companies that specialize in cloud computing and mobile apps. Once high-flying software companies such as Oracle, Microsoft and SAP are losing market share to newcomers such as Salesforce.com, which makes customer resource management software, and Workday, which specializes in cloud-based human resources software. Salesforce, with a market cap of roughly $46 billion, and Workday, with a market cap of less than $16 billion, are far smaller than the old-guard software giants, but they are growing and gaining market share at a much faster rate.

The transition on the software side of the tech industry has been profound. In the 1990s, Internet companies traded on criteria that were largely subjective, such as potential future revenue or potential market share. Few could demonstrate a plan for sustainable growth, and even fewer could show a profit.

However, the revenue model for today’s software companies is different. Cloud company businesses, for example, sell their services on a subscription basis, often with a customer commitment of a year or more, and sometimes with payment received up front, which leads to a more predictable revenue stream. What’s more, cloud computing represents a fundamental shift from hardware to software over the long term. As more services move to the cloud, enterprise customers are shifting their computing budgets from buying hardware they keep inhouse—such as PCs, servers and storage equipment—to buying a package of software services delivered by the cloud provider. At many companies, even the workplace PC, once an office fixture, is being replaced by workers’ own laptops or mobile devices, all connected to the office via the cloud.

At the same time, this shift creates a rapidly growing opportunity for cybersecurity services and software. Security is the top area of spending among businesses looking to protect their networks, for example. As more workers and consumers shift to mobile devices for some or all of their work-related tasks, the need for greater security has continued to rise. In addition, growing demand from changing fields such as health care, in which the use of electronic medical records is being driven by new government regulations, only heightens the need for stronger cybersecurity measures.

Terry Kontos is a managing director and portfolio manager for the TIAA-CREF organization. Justin Lam is a director and equity research analyst for the TIAA-CREF organization. Willis Tsai is a director and equity research analyst for the TIAA-CREF organization.