How Important is Europe to the U.K.?

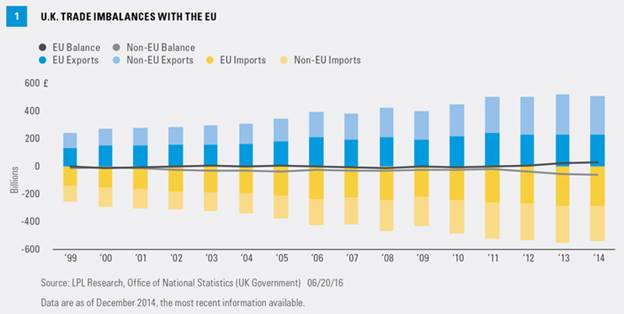

A major issue in the Brexit vote is the impact on trade in goods and services. Figure 1 provides an overview of the U.K.’s total trading relations. A few trends have been impacting U.K. opinion on relations with EU. For example, while U.K. imports from the EU have been increasing since the Great Recession, exports to the EU have been stagnant. The trade picture with the rest of the world is more balanced, with the U.K. running a modest trade surplus with the rest of the world. Politicians in the U.K. have been quick to highlight this rising trade deficit with the EU, suggesting that Europe is dragging the U.K. down.

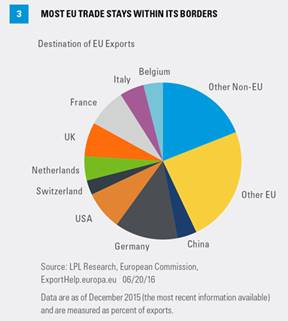

Some have claimed the EU needs the U.K. more than the U.K. needs the EU but Figures 2 and 3 suggest the opposite. U.K. exports to the EU represent 47% of its total exports, with Germany being the single largest destination for exports. It is much more difficult to determine trade within the EU broken out by country. The U.K. denominates trade in pounds, whereas the EU statistics are calculated using the euro. However, examining data from the European Commission shows a basic idea of the magnitude of trade [Figure 3]. Trade from the EU to the U.K. is only about 6.5% of total exports and 10.3% of total inter-European exports. Once again, Germany, at 13%, receives the bulk of European exports and 20.6% of total inter-European exports.

The devil is always in the details.

It’s worth considering the U.K.’s trade relationships with the EU, regardless of the results of Thursday’s vote. There are two components to trading agreements: tariffs (taxes paid on goods at the border) and rules governing trade. Even without free trade zones like those within EU, tariffs on global trade have been steadily declining since the end of World War II. The average tariff on goods between the EU (including the U.K.) and the U.S., its largest trading partner, is 3%. However, it varies considerably by type of product; for example, average tariffs on agricultural products into the EU are 18%. Under the World Trade Organization (WTO), the EU would not be allowed to impose punitive tariffs on the U.K. goods.

Therefore, on its face, the worst case scenario for the U.K. is that its goods would be subject to the same tariff rates as other major countries. Those campaigning for a “leave” suggest that the U.K. will be able to negotiate even these tariffs away; Switzerland and Norway have broader access to EU markets while still remaining outside the formal framework. However, we know where the devil lies. One of the frustrating things for EU opponents is the volume of rules and regulations that membership entails. Given current low tariff rates, it is the negotiation of these rules that drives trade deals. Voting to leave would not eliminate the rules. First, should the U.K. seek to negotiate a separate trade deal (the Switzerland model), it would still be subject to trade rules and regulations. Furthermore, the EU would have every incentive to play hardball with the U.K. in any trade negotiations. After all, if the EU lets the U.K. retain some sort of preferred trading partner status, what is the incentive for other nations not to take the same tact and vote to leave?

The other reality is that the EU works by having each nation’s government formally adopt rules as part of its legal framework. Leaving the EU would not automatically remove these laws from U.K. law. Repealing them would require acts of Parliament and actions by the various U.K. government agencies. Even this is not certain. For example, there may be groups within the U.K. that agree with some of the rules required by the EU, and may advocate for their retention on their own merit, regardless of their EU origin. These might include groups focused on labor, environmental, and consumer protection. Either way, uncertainty—the enemy of markets and economic prosperity—would likely prevail, perhaps for years to come.

No service please, we're British.

Services are also an important part of the trade picture, but trade in services is also much harder to calculate. With physical goods, it’s easy enough (at least conceptually) to count widgets as they cross the border. It is much more difficult to track business services across borders. Financial services in particular are important to the U.K., as London is the European headquarters for many major global banks. We discussed this issue, particularly the importance of “passporting” (the ability of a bank with a presence anywhere in the EU to operate everywhere under equal terms) in last week’s Weekly Market Commentary, “Brexit: Should They Stay or Should They Go?”

We cannot calculate with any degree of reliability the U.K.’s trade surplus with the rest of the EU. However, we know that the U.K. runs a $135 billion dollar trade surplus in services, according the Organization of Economically Developed Countries (OECD). In contrast, Germany, which runs a surplus on goods with most countries, runs a global deficit in trade with services. Therefore, we can infer that the U.K. runs a significant service surplus with the rest of the EU, even though the exact numbers are unknown. This surplus in services helps pay for the U.K.’s deficit on trade it goods. It also provides fairly high paying jobs in banking, insurance, accounting, and other related services. However, this fact also highlights the divisions within the U.K. of more educated and more affluent people, based largely in the major cities, who are benefiting from trade, while traditional manufacturing jobs are perceived to be suffering from it.