Key Points

• China’s government has signaled increased support for the economy, prompting the return of some optimism by market participants.

• China’s official economic data may just say what the officials want it to.

• We provide five indicators that may provide independent insight into whether the Chinese government’s efforts to support growth are succeeding: Caixin China Purchasing Managers Index, commodity prices, Baidu SME Index, Tsinghua UnionPay Advisors Real Estate Index, and Australian exports.

Stocks and commodities began their rally in mid-February after China’s central bank stepped up efforts to restore stability to the yuan and the Chinese economy. China is the world’s second largest economy and the largest consumer of copper and other base metals. The hope of economic stimulus in China has helped spread optimism across global markets. On February 15, the yuan surged the most in a single day against the dollar in over a decade. Global stocks, as tracked by the MSCI All Country World Index, have risen 10% the since the Feb 11 low. Copper futures gained 13% and oil futures are up 37% from February 11 to March 4.

At the start of China’s annual National People’s Congress over the weekend, the government signaled increased support for the economy through higher spending and policy measures to boost lending. The country's GDP growth rate target for this year was set at 6.5-7.0%, supported by an increase in spending that would lift the budget deficit target to 3% of GDP.

While the Chinese government’s efforts to support the economy have prompted the return of some optimism by market participants, a sustained rally will likely depend on those efforts actually working. The data produced by the government statistical agencies in China on borrowing, spending, production, and profits can offer some indication, but the official data may just say what the officials want it to.

Fortunately, we can point to five indicators that provide independent insight into whether the Chinese government’s efforts are working:

1. Caixin China Purchasing Managers Index

2. Commodity prices

3. Baidu SME Index

4. Tsinghua UnionPay Advisors Real Estate Index

5. Asian exports

1) Caixin China Purchasing Managers Index

Purchasing managers indexes (PMIs) are economic indicators derived from monthly surveys of private sector companies. China has two PMIs, one produced by the government, and the other by private financial data provider Markit (known as the Caixin China PMI). Over the past three years, the private sector PMI has consistently provided an overall view of economic activity in China that is weaker than the official PMI.

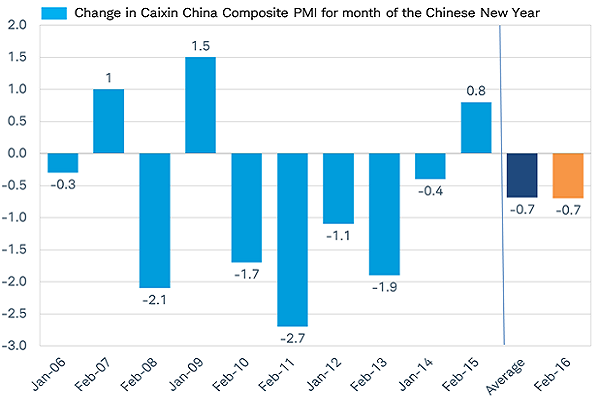

The latest reading of the Caixin China Composite PMI fell 0.7 points. But where it goes from here matters more than the February reading since a 0.7 point drop is actually typical (as you can see in the chart below) for the month of the Chinese New Year, a weeklong floating holiday when businesses across China are shutdown. A rebound, or at least stabilization in the PMI would suggest policymakers’ efforts are being rewarded, while a further decline would suggest otherwise.

Sharp drop in China’s February PMI is typical for month the Chinese New Year takes place

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data 3/4/2016.

2) Commodity Prices

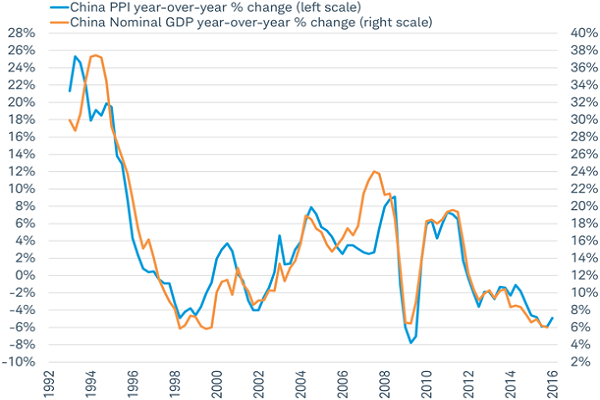

Historically, one of the best indicators of China’s GDP is China’s official producer price index (PPI), which measures inflation at the wholesale level and is largely driven by commodity prices. As you can see in the chart below, the PPI is pointing to stabilization in economic growth in China in the first quarter of

2016. Keeping an eye on market-determined commodity prices, especially for those used in production like copper and oil or infrastructure like iron and steel, may offer a signal on the pace of growth in China.

Producer prices pointing to stabilization in China’s economy in the first quarter

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 3/4/2016.

3) Baidu SME Index

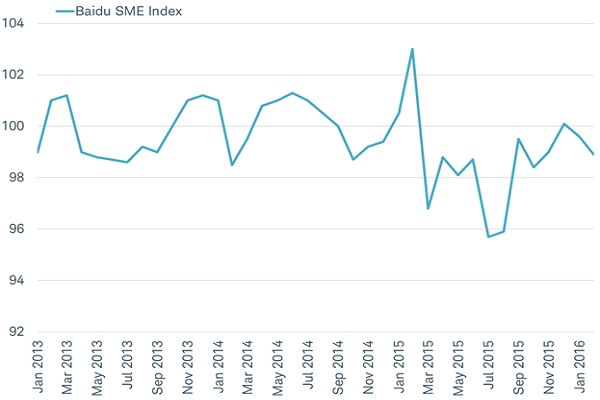

The official data on retail sales in China shows a relatively stable trend of double-digit growth over the past year. An alternative to these official figures, the Baidu SME index, has been telling a different story. This index is based on internet searches on China’s dominant search engine for the products and services of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Readings below 100 signal deterioration. This index fell to 98.9 in February suggesting demand for SMEs' products and services may be reversing the rebound seen in the second half of 2015. As consumers and small businesses have become powerful forces in China; a further slowdown in this index would suggest policies to support growth may be failing.

Internet product searches in China maybe rolling over after rebound in late 2015

Source: Charles Schwab, Baidu data as of 3/6/2016.

4) Tsinghua UnionPay Advisors Real Estate Index

China’s real estate market has been a source of concern for investors after property prices began to fall in 2014. However, a recovery unfolded in 2015 and appears to be gaining momentum according to official data from the China’s National Bureau of Statistics. A privately produced measure of the volume of housing transactions known as the Tsinghua UnionPay Advisors Real Estate Index can offer us impartial insight into the pace of housing activity in China. This index measured 18% year-over-year growth in Chinese property purchases in January as lending surged. Readings in the months ahead may be a useful gauge of the success of new policies, like a reduction in down payments and lending rates, intended to support housing.

5) Asian exports

China is Australia’s largest customer, being the destination for more of Australia’s exports than Japan, the United States, and Korea combined. For January, Australia’s exports were down -6.7% from a year ago, but posted a 1% gain for the month—the first monthly gain in exports in four months. South Korean exports may also provide a useful gauge of China’s growth since mainland China makes up 25% of Korean exports. Like Australia, Korean exports has been weak lately, but the year-over-year pace of exports to China eased in February to -16.0% from -21.6% in January. Unlike the other four indicators, this Asian export data isn’t complied by a private-sector source. But since it comes from the Australian Board of Statistics and Korean Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy and not from the Chinese government, it is less likely to be biased in its take on China’s demand growth.

Trust but verify

“Trust, but verify” is always a good approach for investors. These five monthly independent measures of China’s economy may help to confirm or refute the trends in the data produced by the Chinese government and offer insight into the sustainability of the rebound in the markets. If the Chinese economy appears to be slowing, but not crashing, markets participants may be relieved. On the other hand, widespread weakness in the independently produced data may lead to the return of selling by global investors.

Jeffrey Kleintop is senior vice president and chief global investment strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.

Read more here.