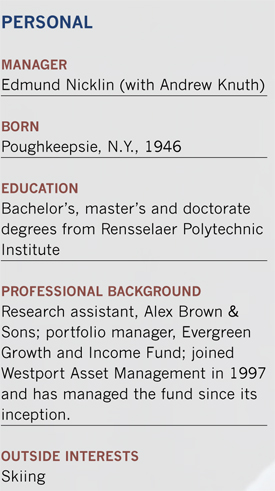

It's tough to snag Ed Nicklin for an interview when quarterly earnings reports are coming out. It's his peak hunting season. The 63-year-old manager of the Westport Fund likes the stocks of out-of-favor companies, those with problems he thinks can be solved or those with advantages yet to be recognized. Often, his interest is piqued when promising companies' earnings reports come in below expectations, driving their stock prices down. For him, that's a buying opportunity.

"A lot of money managers look for substantial and consistent earning gains," he says. "I'm more concerned with whether or not management is making progress and moving the value of the business in the right direction."

In an era of index-hugging and the liberal use of computerized quantitative screens, Nicklin and co-manager Andy Knuth do neither in their mostly mid-cap fund. Instead, they go case by case when picking stocks, and keep their eye on the news. Their research can lead to surprising finds. Some of the names in their portfolio, such as Abbott Laboratories or FedEx Corporation, are fairly commonplace among mutual funds. But others, such as the Dr. Pepper Snapple Group or medical instrument company Beckman Coulter, suggest that the two managers aren't afraid to step off the beaten path.

"Academic studies suggest that 60% of a stock's price movement on a given day is due to overall market activity. But if we're doing our job right, we can add value by finding companies with the potential to improve the value of their businesses," says Nicklin.

Although he focuses on each company's particular issues, he isn't blind to the impact that global economic and market developments have on his portfolio. "I've been in this business for many years, and the degree of leverage that the U.S. and other countries are taking on now is unprecedented," he says. "This is really uncharted territory. By its very nature, leverage causes things to occur that wouldn't without its presence."

At the same time, he is concerned that the current U.S. monetary policy designed to stimulate the economy is "setting the table for inflation" and he believes that slightly higher interest rates for borrowers might be in order now that the worst of the economic emergency in this county seems to have passed.

Even if regulators take steps to avoid market routs like the one that occurred in early May (when trading systems triggered automatic stop orders), trading downdrafts will still occur. "Are we going to see market blowouts? Yes. But there are also going to be opportunities to pick up stocks of good companies that have been overly punished by investors."

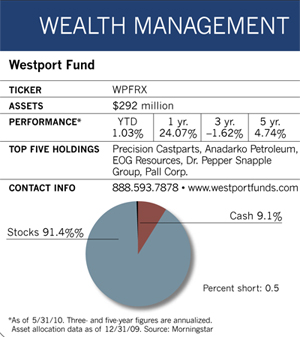

It is just such stocks that have helped the Westport Fund earn a five-star Morningstar rating and substantially outperform the benchmark Russell Midcap Index since launching in 1997. The Westport Fund was also the top-performing portfolio in Lipper's multi-cap core category over the five years ended December 31, 2009.

Over the last year, though, Westport underperformed the benchmark while the market favored riskier companies with little or no earnings. The fund has also underweighted consumer discretionary and financial services, two sectors that have done well in the economic recovery.

Despite the fund's more recent plodding, Jack Chee, an analyst at investment firm Litman/Gregory in Larkspur, Calif., says the team's approach has worked well over long periods and he finds the firm's patient strategy a refreshing break. "We like that they run reasonably concentrated portfolios and do not attempt to know hundreds of companies, they stick to what they can understand, they have minimal non-research distractions, and are focused on investing," he wrote in a recent report. Knuth recently turned 70, and Nicklin is in his early 60s, but Chee reports they have no imminent retirement plans.

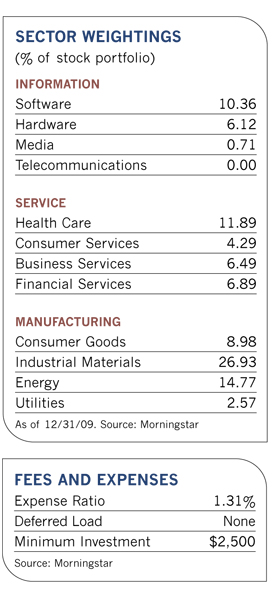

Although Nicklin is not constrained by company size, the concentrated portfolio of about 45 stocks is mostly in mid-cap territory. About 55% of the names have market capitalizations of $2 billion to $10 billion. Larger companies with public values of between $10 billion and $50 billion account for another 35% of the portfolio. The team has cast its net into widely diverse sectors, with business products and services taking the lead at 15.1% of assets, followed by industrial specialty products at 14.3% and oil and gas producers at 12.1%.

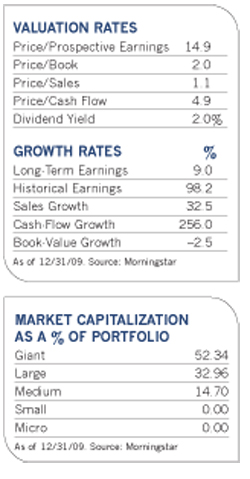

The fund shuns risk by steering clear of companies with chronic issues that can drive them to their knees in the long run, such as a portfolio of bad loans or a shrinking customer base that shows little promise of growing. Instead, the fund moves in when a company falls out of favor with Wall Street for what is likely to be a temporary problem. Nicklin buys names selling below what he considers intrinsic value, which he defines either as what a private buyer might pay or what he believes a company's value would be on the public market in a turnaround when everything else at the company is running smoothly.

It's not only disappointing earnings that cause a stock's price to hiccup. Sometimes a company is hit by a regulatory curveball. Other times, investors get shaken up about all the debt they see after an acquisition or a spin-off. But if a company can overcome those obstacles-by generating free cash flow, for instance, or by showing some other advantage steering it in the direction of long-term profitability-then Nicklin will consider buying. His interest is also aroused by changes in corporate management, by new products or by any other developments that suggest a good change in fortune at a company.

In a turnaround such as an acquisition or a stock buyback, Nicklin is willing to wait as long as two years to see how it pans out and will often hang on long after that if the premise for owning the stock still holds. His long-term outlook is one of the reasons that the portfolio turns over at about one-tenth the rate of the average stock fund. Once a stock reaches a predetermined price target or its fundamentals deteriorate or the premise for buying it no longer holds, Nicklin will likely sell it.

The portfolio's holdings include FMC Corporation, a diversified chemical company serving agricultural, industrial and consumer markets. Nicklin bought the stock soon after the company released a disappointing earnings report. A new holding, Beckman Coulter, makes instruments, chemicals and software for laboratories. This stock suffered a setback after problems were discovered with one of its lab tests. Nicklin believes the issue is neither huge nor lasting.

These stocks join the longtime fund holding Dr. Pepper Snapple Group. Nicklin first began buying the stock two years ago, after former parent company Cadbury Schweppes loaded the company down with debt as part of a spin-off. The stock languished for months as the Snapple brand lost its luster and sales lagged in the slowing economy.

Nicklin believed the company had a number of things going for it-a recognizable name and a loyal base of fans, including a number of friends who considered the taste truly unique. "The company improved distribution and was able to expand geographically and into fast food restaurants such as McDonalds," he says. "And it recast Snapple as an all-natural product by replacing corn syrup with sugar and changing its packaging." A $900 million windfall from Pepsi for the rights to distribute Snapple product was an unanticipated bonus.

One of the smaller companies in the portfolio is Baldor Electric. Nicklin first bought this stock three years ago when Baldor acquired a competitor, saddling itself with a large amount of debt in the process. But the deal paid off by opening up new markets to the company and by lowering its operational costs. With its ample free cash flow, Baldor has made significant progress in paring down its debt.

Nicklin's requirement that companies have a competitive advantage knocks out most commodity plays from his consideration, since recycling helps ensure an ample supply. An exception to this rule is oil stocks. "Oil is a different animal because it is so integral to growth in countries around the world. And you can't recycle oil. You have to keep finding it."

The fund bought a position several years ago in Anadarko Petroleum shortly after the company announced its acquisition of two major competitors for more than $23 billion. The deal left Anadarko deeply in debt, and when its stock fell, Nicklin moved in. Later, the driller's fortunes improved as its global exploration programs proved fruitful and its balance sheet improved as it sold off assets to pay down debt.

Nicklin believes the company, which has some of its operations in the Gulf of Mexico, can deal with the setbacks created by the area's recent oil well disaster. "Oil companies operating in the area will see new regulations that increase the cost of drilling in the region," he says. "But over the long term, I think they can absorb the additional expenses and operate in an environmentally acceptable fashion."