“Complacency breeds failure. Only the paranoid survive.”

– Andy Grove (founder and CEO of Intel)

John Maynard Keynes introduced the concept of “animal spirits” as it relates to economic activity in his 1936 book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. The term “animal spirits” is a way to describe what drives human behavior to consume, take risk and engage the instinctual proclivities that are natural to economic living. This important piece of Keynes’s work came seven years after the Great Depression and we think the concept is critical to understanding the economy and markets of today, eight years after the biggest recession since the period he was addressing.

Most economists agree a critical component has been missing in our economic recovery. We have very attractive national housing affordability, our economy is operating at full employment levels and median household incomes have surged for the first time since 2007. At the same time, we sit at historically low interest and mortgage rates that are begging people to buy homes. The average U.S. household has the room in their income statement to add monthly payments and they are currently paying more for rent, in many cases, than they would be if making a house payment.

In fact, 76% of millennials say they are planning on buying a home, yet homeownership levels under the age of 35 continue to set five-decade lows. The velocity of money, a measurement of how often a dollar is turned over in the economy, sits well below the all-time lows of the last 60 years. Many corporate balance sheets are flush with cash earning next to nothing and households are living the furthest inside their means since 1980. The barn door has now been fully closed from the 2008/2009 recession after the farm animals had left the stable years ago. What we need are new “animal spirits” to populate our economic barn.

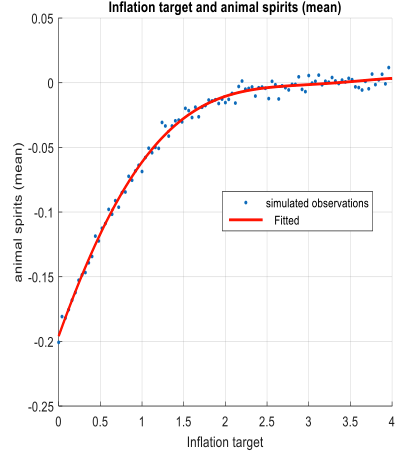

A little inflation may be an important animal to add to the stable. Paul De Grauwe, a professor at the London School of Economics, and Yuemei Ji, from University College in London, have given a framework for understanding how “animal spirits” relate to various levels of inflation:

The U.S. Consumer Price Index, a proxy for inflation, has been hovering around a very tepid 0.5% – 1.0% level since the end of 2014. De Grauwe and Ji created an “animal spirits” index which measures the optimism or pessimism among economic participants for future economic output. Their thesis argues that if inflation converges too close to zero, humans gravitate towards certain cognitive limitations that prevent them from using rational expectations. These economic agents are left using simple rules of thumb that extrapolate the future by leaning on the past. The past gives them no observable reason to cause engagement in economic activity today and chronic pessimism sets in. This negative feedback loop results in persistently lower consumption and investment activity which lowers long-term future growth.

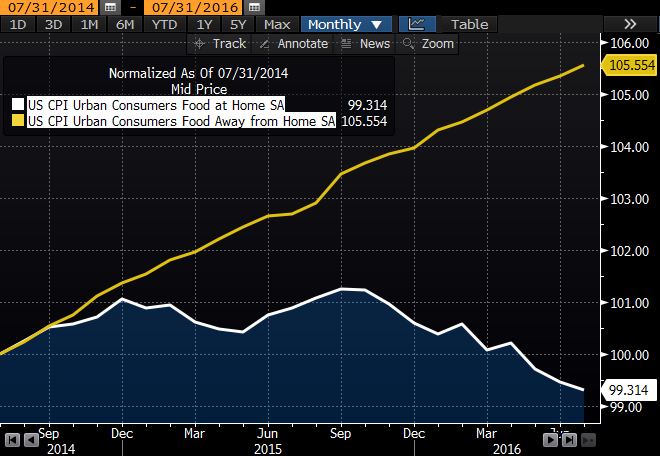

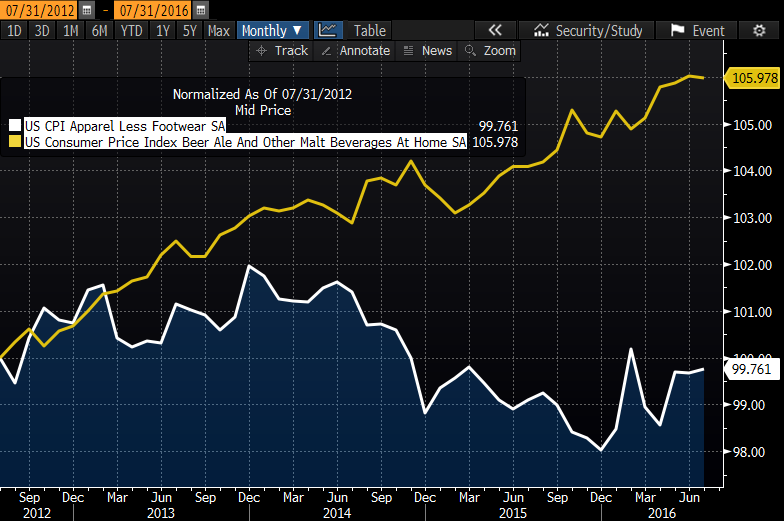

One example of this can be observed by the recent differential of inflation in the grocery store aisle vs. the price of eating out. Over the last several years, you spend 5-6% more to eat out, while grocery bills are flat to down 1%. This may not sound like much, but it’s caused havoc in the stock prices of grocers recently. Similar examples can be found in apparel retailers. One of the beautiful things about economics is that these low prices eventually become natural stimulants that can activate the “animal spirits” that drive future spending. It is not lost on us that groceries and apparel are critical ingredients to forming and growing households. Once millennials stop drinking all the craft-beer, eating all the burgers from Shake Shack, chomping all the Chipotle burritos or upgrading to the latest smart phone, they may wake up in a grocery store or a local clothing retailer with some good news! See the charts below1:

Nothing has been as disinflationary as the price of money. Interest rates are historically and ridiculously low, but in an economy trending towards the lower range of inflation, taking action is deferred. If we use the baby-boomer’s experience from 1975-1995 as a roadmap, economic engagement is driven by need and changes with age. The subsequent demand-based multiplier effect created by household formation/home buying, child bearing and auto buying drove the velocity of money and prices higher, which caused market activity to set higher interest rates. The Fed will find itself arriving late to the party and having to play catch-up as millennials change with age.

The boomer generation tells us something else: inflation – sustained and meaningful inflation – did nothing to stop this activity, and in fact, may have acted as a positive catalyst. After all, you were compelled to lock-in your mortgage at 10% when it had been at 8% not too long before, leaving you to extrapolate a 12% rate around the corner!