The potential downgrade of over $100 billion worth of investment-grade rated bonds into the high-yield market looms as the next challenge for corporate bonds. The decline in oil and commodity prices may lead to $120–150 billion worth of bonds leaving the investment-grade corporate bond market and entering the high-yield bond market. Absent a significant reversal in oil and commodity prices, the high-yield market will have to absorb a significant amount of new supply and an increase in troubled energy sector bonds. The size of the investment-grade bond market (in excess of $4 trillion) is much larger than that of high-yield (approximately $1.2 trillion), so the influx of “fallen angels” is a greater concern for the high-yield bond market.

Sidebar: A fallen angel is a bond issue that has been downgraded from investment-grade (usually from BBB-, the last rung of investment-grade ratings) to high-yield (rated BB+ or below).

With an influx of fallen angels anticipated, forward-looking bond markets have already made adjustments. The average yield advantage, or spread, of investment-grade corporate bonds to comparable maturity Treasuries has widened steadily in recent months [Figure 1]. The average yield spread has increased to 2.0%, the highest since late 2011 in response to European debt fears.

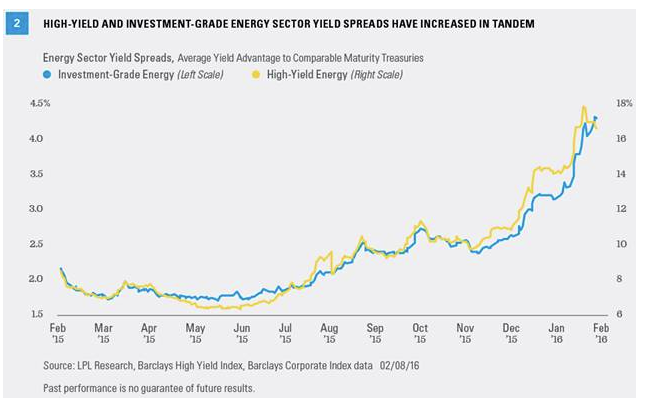

The rising yield spread represents investors demanding a growing risk premium in response to the deterioration in credit quality of energy- and commodity-related issuers due to the persistence of low commodity prices. Like the high-yield market, energy issuers are the primary driver behind higher investment-grade yield spreads, and thus cheaper valuations [Figure 2].

Rising yield spreads also represent market participants’ broad credit quality concerns, but excluding the energy sector, the average yield spread of investment-grade corporate bonds is 1.7% (according to Barclays Index data as of February 2, 2016), not far above the 1.3% long-term (15-year) average. So although investors have some concern about credit quality deteriorating broadly, the energy sector is clearly the focal point. Any concern over broad investment-grade corporate bond quality, if not already factored into current valuations, would likely be in response to the general economy and not energy downgrades.

Another High-Yield Challenge

The potential influx of fallen angels may increase the size of the high-yield bond market by as much as 10%. The high-yield energy sector, now 11% of the overall high-yield market, could potentially increase to 21%. Such an increase could add to pressure on high-yield bond prices after an already difficult six-month period. Forced selling by investors who are unable to own bonds rated below investment-grade could further pressure high-yield bond prices, and energy bond prices in particular.

Two prior examples may provide a glimpse of what investors can expect:

· In 2005, two major auto companies officially entered the high-yield market via downgrade on May 6, 2005. Their entrance increased the size of the high-yield auto sector from 3% to 14% of the overall high-yield bond market. However, weakness in the auto sectors of both investment-grade and high-yield markets was evident in early 2005. At the time of the downgrade, the high-yield auto sector had already declined by approximately 16%, with investment-grade autos down nearly 12%. High-yield auto sector weakness persisted for a week after the downgrade, as forced liquidations occurred before the broad high-yield sector rebounded.

· In 2002, continued fallout from the dot com and telecom bust of the late 1990s drove corporate bond weakness, and approximately $130 billion worth of investment-grade bonds were downgraded to “junk” (high-yield) status. Markets moved in anticipation, but corporate accounting scandals that began at WorldCom in June 2002 exacerbated weakness and delayed the eventual recovery. The market reached a bottom in October 2002 before moving steadily higher, as investors took advantage of cheaper valuations.

Different This Time?

Since the end of the Great Recession, investor mandates have become more flexible, implying that forced selling accompanying ratings downgrades into high-yield status may not be as pronounced as in prior years. Many investors, while restricted from purchasing high-yield bonds, may have exceptions for existing holdings that could be downgraded. Forced selling of Puerto Rico bonds in the municipal bond market was relatively modest and occurred well in advance of eventual downgrades into high-yield. Although Puerto Rico comprises over 20% of the high-yield municipal market, impact was muted when the downgrade finally arrived and remained specific to Puerto Rico issuers. The taxable and tax-free bond markets are different animals, but historically, bond prices have mostly adjusted in advance of downgrades.

Implications

History shows that during periods of significant downgrades and falling angels, bond markets often adjust in advance. In 2002, a lack of trust sparked by corporate accounting scandals fueled additional weakness delaying an eventual recovery. In 2005, reversal occurred soon after the arrival of the downgraded auto companies. In the tax-free high-yield market, adjustments occurred well in advance of downgrades. A similar adjustment may already be underway in anticipation of downgrades, but the timing remains uncertain. In the current environment, uncertainty over the timing and magnitude of energy downgrades could cause pressure on corporate bonds to linger despite already compelling valuations for longer-term investors.

Anthony Valeri is investment strategist for LPL Financial.