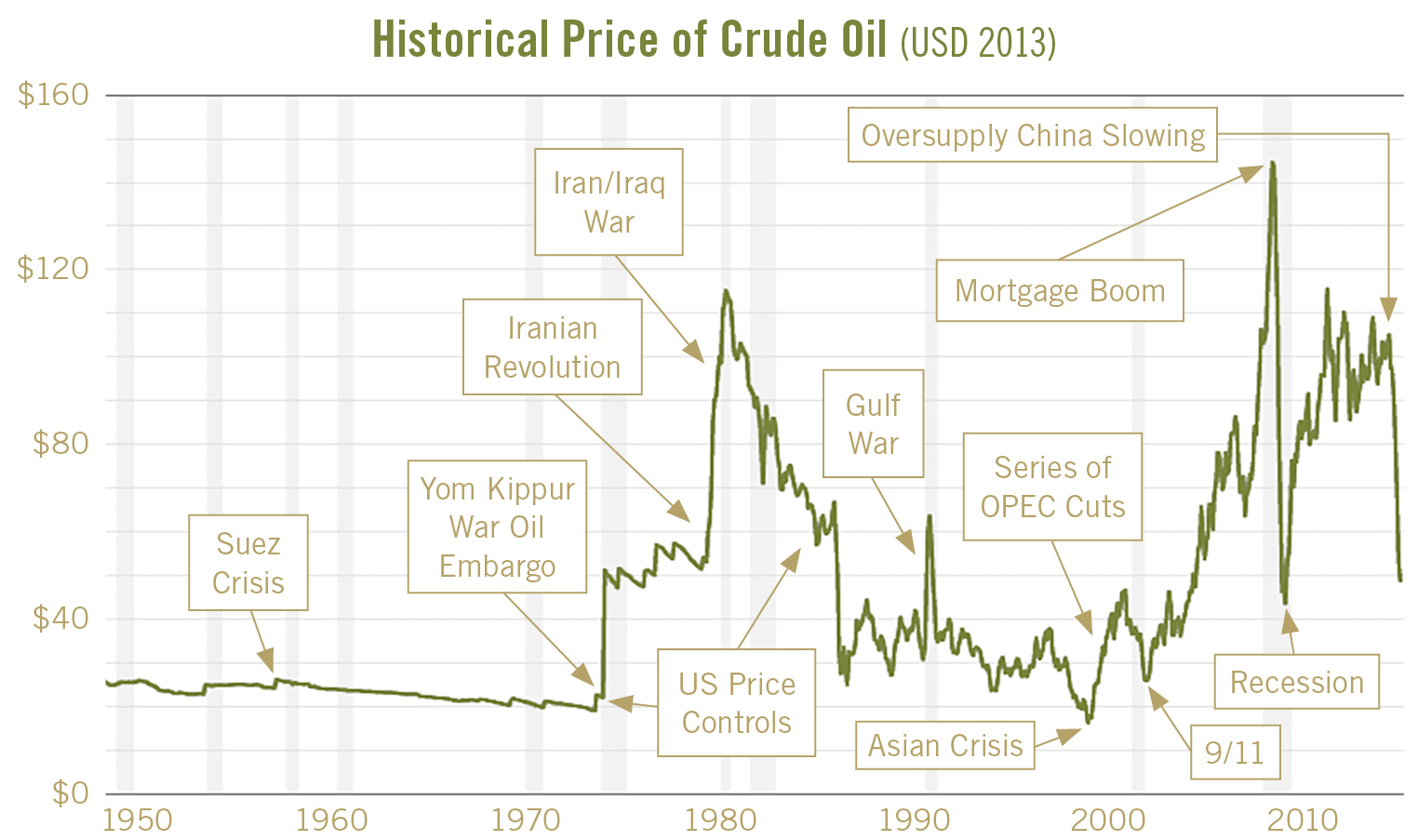

Throughout most of the 20th century, the price of U.S. petroleum was heavily regulated through production or price controls. From post World War II to the early 1970’s, crude prices ranged from $17 to $19 per barrel in 2013 dollars. However, the Yom Kippur War, begun in October 1973 with an attack on Israel by Syria and Egypt, changed the global petroleum landscape. Several Arab exporting nations imposed an oil embargo on the countries supporting Israel, including the U.S. By the end of 1974, 7 percent of free world production had been curtailed and the price of oil had quadrupled. Since then, the price of crude has proven both volatile and highly unpredictable, as modest changes in supply or demand realities, or expectations, holds substantial sway over the short term direction of oil prices.

Despite the new energy paradigm since the 1970s, there have been only a handful of times in the last four decades where the price of oil has fallen as much as it has in the last six months.

A foreshadowing of the damage that can be caused by greed, regulatory loopholes and leverage (harken back to the 2007-8 mortgage crisis, magnified by the plethora of levered mortgage backed securities), the 1985-1986 oil price decline was probably amplified by the unwinding of energy-based tax shelters. The highest marginal personal tax rate was 50 percent to 70 percent in the 80s; thus, many wealthy people put their money into energy-backed tax shelters designed to produce tax write offs. 1986 was a perfect storm of burgeoning crude supply and tax reform which lowered marginal rates and disallowed windfall profit tax and other tax deductions. The rapid unwinding of tax shelters likely exacerbated oil’s decline and could have provided a lesson to regulators regarding speculation and leverage in asset backed securities.

1998

From 1990 to 1997, world oil consumption increased 6.2 million barrels per day according to the WRTG, driven primarily by the booming Asia Pacific region. Hoping to capitalize on Russian production declines and most likely underestimating the massive overinvestment in Asia, OPEC increased its production quota by 10 percent in late 1997. For a variety of reasons, the explosive growth in emerging markets came to a standstill in 1998; the price of oil plunged 50 percent, numerous currency shocks threatened financial contagion and (once again) unregulated, levered currency derivatives imperiled the US financial system, culminating in the high profile government sponsored bailout of hedge fund Long Term A month ago, on Thanksgiving Day, much to the surprise and dismay of global oil producers, drill equipment manufacturers and oil stock investors (among others), the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decided to maintain rather than reduce its target production quota of 30 million barrels per day. In addition, Saudi Arabian oil minister Ali al-Naimi said, “it is not in the interest of OPEC producers to cut their production, whatever the price is. Whether it goes down to $20, $40, $50 or $60, it is irrelevant.” Commodities markets clearly expected a much more accommodative response to already weak crude prices; at minimum, a half million barrel per day reduction was priced into the November 27 meeting. The response was swift and punishing. In the following 2½ weeks, crude fell 25 percent from the mid $70s to $53 per barrel today — 50 percent below June’s $110 peak. This year’s downdraft is not unprecedented: The crude oil cycle regularly experiences wide price swings in times of shortage, oversupply or exogenous events such as war or natural catastrophe. The duration and magnitude of the price cycle is an imperfect function of global oil policy response and market expectations for price mean reversion. It seems unlikely the price of crude will stay in a narrow $50-$60 range in 2015, which seems to be consensus among economists. U.S. shale oil production from fracking and recovering Libyan shipments might easily be offset by economic turmoil in Russia or Venezuela or a reversal in OPEC production strategy.

A month ago, on Thanksgiving Day, much to the surprise and dismay of global oil producers, drill equipment manufacturers and oil stock investors (among others), the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decided to maintain rather than reduce its target production quota of 30 million barrels per day. In addition, Saudi Arabian oil minister Ali al-Naimi said, “it is not in the interest of OPEC producers to cut their production, whatever the price is. Whether it goes down to $20, $40, $50 or $60, it is irrelevant.” Commodities markets clearly expected a much more accommodative response to already weak crude prices; at minimum, a half million barrel per day reduction was priced into the November 27 meeting. The response was swift and punishing. In the following 2½ weeks, crude fell 25 percent from the mid $70s to $53 per barrel today — 50 percent below June’s $110 peak. This year’s downdraft is not unprecedented: The crude oil cycle regularly experiences wide price swings in times of shortage, oversupply or exogenous events such as war or natural catastrophe. The duration and magnitude of the price cycle is an imperfect function of global oil policy response and market expectations for price mean reversion. It seems unlikely the price of crude will stay in a narrow $50-$60 range in 2015, which seems to be consensus among economists. U.S. shale oil production from fracking and recovering Libyan shipments might easily be offset by economic turmoil in Russia or Venezuela or a reversal in OPEC production strategy.

1986

The year 1986 witnessed one of the most dramatic waterfall declines in oil price history, stemming from a combination of Saudi policy reversals and derivatives on oil futures. From 1980 to 1986, crude prices fell as demand shrunk due to structural/behavioral declines in oil usage stemming from the 1970s oil shock and lower consumption during the 1979-1982 recession. Simultaneously, non-OPEC exploration and production, driven by tantalizingly high oil prices in the late 1970s, increased output by more than 6 million barrels per day. OPEC was facing lower demand from non-OPEC nations who sought greater energy independence. In response, from 1982 to 1985, OPEC attempted to set production quotas for its members low enough to stabilize prices. But OPEC members repeatedly cheated and produced beyond their allotment, leaving Saudi Arabia to act as the swing producer to stem the freefall in prices. Tired of losing money and market share at the expense of the rest of OPEC, in August 1985, the Saudis linked their oil price to the spot price and increased production from two to five million barrels per day. Oil prices fell 60 percent in eight months and stayed relatively stable until the Gulf War in 1990.

Capital Management. OPEC responded rapidly by cutting production three times, alleviating price pressure.

The Oil Price Plunge: We’ve Been Here Before

February 2, 2015

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment