One of the first clients I ever worked with was a gentleman by the name of Doug Durst. His firm was called “Durst and Associates,” but Doug was working solo. He told me once that his clients kept telling him, “Doug, we see you, but where are the associates?” He realized it was time to take action, and soon after hired his first “junior advisor.”

“Junior” advisors are critical for the success of a firm, but their roles and responsibilities in an advisory firm are often misunderstood and frequently mismanaged. To begin with, “junior” advisors hate being called “junior.” They are often neither young nor inexperienced, and while they are not yet at the top of their professions, they can make an immediate contribution to the productivity and profitability of any firm.

In fact, many firms have yet to hire their first junior advisor. Some practices, particularly solo ones, have a hard time with the notion of anyone else working with their clients. They feel the same way about another advisor being with their clients as I feel about my wife dancing with another man—technically not a problem, but it can’t be happening all the time.

Unfortunately, if an advisor sees client relationships as “personal relationships,” they will have a hard time building a business beyond their personal practice, and they are probably better off not hiring associates.

Other firms are interested in the concept and willing to give it a try but struggle with the job descriptions and an understanding of what the associates will do. These are the firms that we hope can use this article to begin a discussion of what “juniors” can do in their firm.

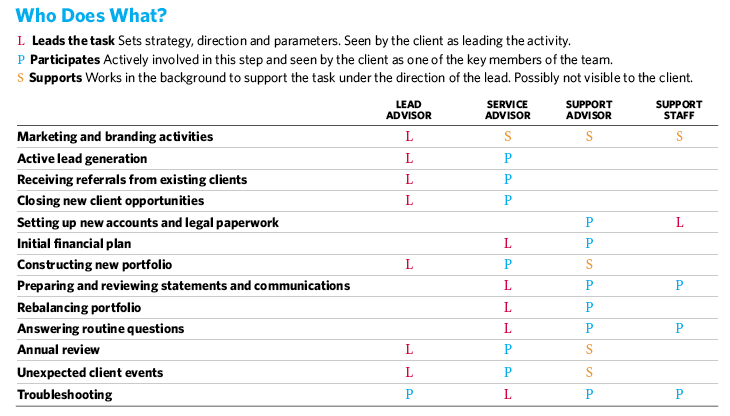

Our consulting experience has been that there are at least three distinct levels within the advisory profession. These positions are well understood in large firms, but smaller firms still struggle to define them.

• Lead advisor. This person works with the clients and is responsible for the client relationship.

• Service advisor. This is the first of the “junior” positions. The service advisor is often a CFP (44% of them are) and highly experienced (with a median of eight years of work). This advisor works with clients to provide a mix of advice, planning and investment management. He or she spends a lot of time in front of clients and may even be handling client relationships independently.

• Support advisor. This person, also known as an analyst, paraplanner or associate advisor, works at the entry level and is focused on technical work, including the drafting of plans and the preparing of analysis for use by lead advisors. But even though it’s an entry level job, 20% of the people in it are CFPs with a median experience level of four years.

Smaller firms have trouble defining the responsibilities of the “non-lead” advisors, so I thought it may be helpful to summarize our experience.

(The table show each person’s role in an activity.)

For example, service advisors will frequently take the lead in answering routine client questions (such as, “I noticed the S&P is up 18%, but my portfolio is only returning 12%,”) and may use the help of a support advisor in researching some of the answers. But the leader will be taking charge of new portfolio construction, while the service and support people help as needed.

This table is meant to provide an example rather than a universal answer. First of all, not every firm will have both service and support advisors. Some firms may only have one “non-lead” position and may combine the responsibilities of a service and support level into one. Some firms may have both levels on their organizational chart but not on every team. If this is true, the actual team-level responsibilities may be blurring the positions a bit.

There are also firms that have an investment department and an advice department where the responsibilities may be more complex and each department has its own career track.

But the point is that the “non-lead” positions can and do play a very important role in the delivery of services to clients. They should create capacity for the lead advisor (notice all the boxes the lead does not have to check) and leverage (it is quite likely that some of the non-lead advisors may even be better than the lead advisors at some of the tasks).

Inviting the service and support advisors to the client meeting is often a difficult first step for many advisors. They are afraid there will be too many “chefs” in the kitchen and that the subordinates will say or do something to damage the client relationship.

But it’s also a mistake to invite the service advisors to the meeting and not give them much of a role. They end up sitting silently for the entire meeting with no apparent function, and it’s difficult for the client to see them as an integral part of the service team. Once a colleague of mine was supporting me in a client engagement and sat silently through the entire meeting while I “hogged” the conversation. The client got up to leave and said to my colleague, “Good that we are paying you by the word.”

The moral of this story is, don’t just bring service advisors to a meeting. Give them a very specific role and give them a chance to shine. If clients are going to accept them as “authoritative” members of your team, they need to see them in action.

At times, the owners of a firm also make an error in thinking that the “junior” advisors should work mainly with the small client relationships. The logic is that it will create capacity for the firm owners and that the risk of losing those clients is much more tolerable.

This is flawed in two ways:

• First of all, throwing an advisor who is not ready to work independently into a “small” relationship is just bad business. The experience of both the client and the advisor will be very frustrating, and any problems that develop are still likely to reflect on the reputation of the firm. A firm should never have clients it is willing to “experiment on.”

• The service advisors are also not very likely to learn much from this experience. The challenges presented by small relationships are not likely to help them learn how to service bigger ones. In chess, they say, you learn the most when you play opponents who are better than you; worse opponents just teach you bad habits. Similarly, advisors will form bad habits if they only deal with simple and uncomplicated client problems.

A much better policy is to have the service advisors participate in large client relationships and perhaps test their ability to lead with both clients large and small to see who responds better to their style.

To successfully work with service and support advisors, a firm needs to have a well-structured client service process. Otherwise it is very difficult for both the lead advisor and the service advisors to understand their roles. In a way, before hiring a sous-chef in the kitchen, a restaurant has to write down its cooking recipes. Your table of responsibilities may not look much like the one I have proposed, but if you cannot create a table at all, then hiring a service advisor will be very frustrating for all parties involved.

Finally, hiring “non-lead” advisors is also a function of the size of the client relationships. Smaller projects are better done by one person—the cost of explaining the steps and circumstances is higher than the benefit of leverage. In a way, you don’t need two chefs to make a cup of coffee—it will have to be a more complicated recipe. Firms with larger and more complex relationships will find it easier to leverage service and support hires.

Hiring service and support advisors is a critical step for advisors who want their businesses to become larger and better. These positions not only bring capacity and leverage to your firm but challenge it in some very positive ways. By creating a place for them, you force discipline on the organization. It puts the responsibility on you to create opportunities for those hires to grow their careers and someday become lead professionals. It forces your firm to not only create the career path but also, very importantly, to find the new clients and new markets that will enable that growth.

Philip Palaveev is the CEO of the Ensemble Practice LLC. Philip is an industry consultant, author of the book The Ensemble Practice and the lead faculty member for The Ensemble Institute. More information about the institute can be found by e-mailing [email protected].