I. Our Greatest Fear Of The Moment

One of our greatest fears today is the coming rise in interest rates. The concern is that when rates rise, not only will bond prices fall, but rising rates will also undermine equities, driving stock prices down. But is this a rational fear? Does it have any historical basis? The argument presented here is quite the opposite. Historically, stocks have performed favorably during such periods. Let’s explore the issue.

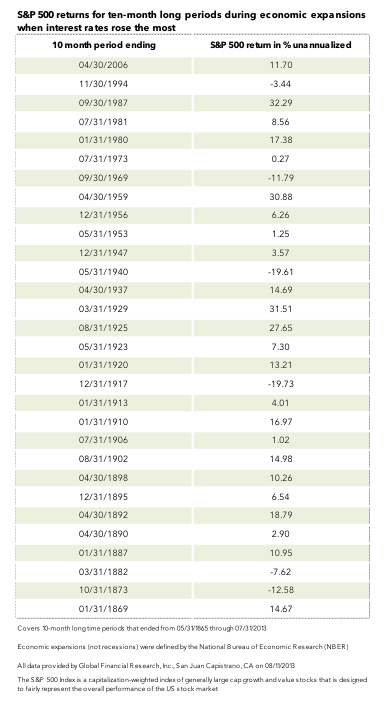

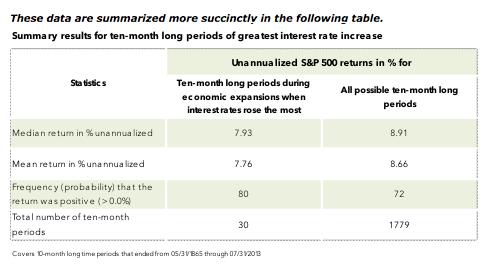

The median return for all 10-month windows when interest rates rose the most was 7.93%. This compares favorably to the median of all possible 10-month-long windows of 8.91%. Perhaps more interesting, however, is that 80% of 10-month windows of greatest interest rate increase delivered positive stock market returns. In contrast, only 72% of all possible 10-month windows generated positive S&P returns. Based on these 30 economic expansions, it would appear that rising interest rate environments are not detrimental to equity market returns.

IV. Conclusions

II. Is Our Fear Based In Fact?

Eventually, the U.S. Federal Reserve will reverse its history-making efforts to hold down intermediate bond yields and associated residential mortgage rates. At that time, it is feared that interest rates will rise across the board and that this will undermine stock market returns. To analyze this fear, let’s examine stock market returns during periods of economic expansion when interest rates have risen the most. Specifically, I restrict the analysis to periods when the U.S. economy was not experiencing an economic recession as defined by the official body that designates such downturns, i.e., the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Since 1865, we have experienced 30 economic expansions, not including the current period of growth. The shortest of these expansionary phases lasted 10 months. For this reason, I selected the 10-month-long window within each growth period during which interest rates rose the most. For this purpose, I used the current yield on the 10-year constant-maturity U.S. Treasury bond. The following table provides the total return on the S&P 500 for these 10-month-long windows during which interest rates rose the most.

III. Examining More Recent Economic History

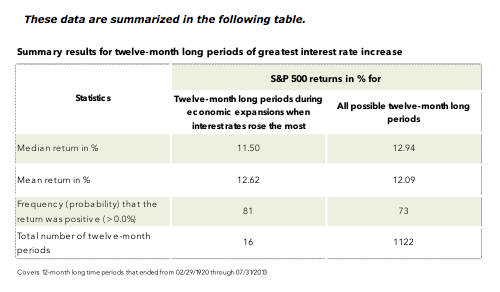

If we constrain ourselves to more recent economic history, the above result holds even more strongly. Since 1919, we have experienced 16 economic expansions, not counting the current. The shortest of these growth phases lasted 12 months. Therefore, as before, we identify the 12-month-long window within each economic expansion during which interest rates rose the most. The data are presented in the following table.

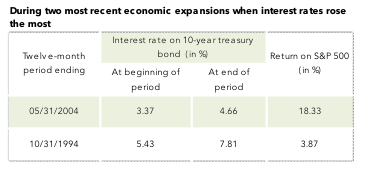

The median 12-month return during periods when interest rates rose the most was a favorable 11.50% for the S&P 500. This compares to a median return of 12.94% for all possible 12-month windows (whether interest rates were rising or not and whether our economy was in expansion or contraction). But of greatest interest, 81% of the 12-month windows of most rapid interest rate increase delivered positive S&P returns. This is in contrast with only 73% for all possible 12-month windows. We can perhaps gain greater perspective on what lies ahead for the U.S. stock and bond markets by reviewing the last two episodes in further detail. The following table shows the results for the two most recent periods.

Setting aside the current ongoing economic expansion, the last growth phase ended with December 2007, just prior to the Great Recession. During that growth phase, the 12-month period that experienced the greatest interest increase ended May 2004. During that interval, the yield on 10-year Treasurys rose from 3.37% to 4.66%, a remarkable 38% proportionate increase. Nevertheless, the S&P 500 was still able to deliver a positive 18.33% return during this 12-month period.

Similarly, in the prior economic expansion that ended in March 2001, interest rates experienced the greatest rise during the 12-month-long window ending October 1994. During this yearlong period, Treasury yields rose from 5.43% to 7.81%, a 44% proportionate increase. Nevertheless, the S&P 500 still returned a favorable 3.87%.

All other things held constant, an increase in interest rates should reduce stock prices. This occurs because the present discounted value of future dividends falls in direct conjunction with rising interest rates. But of course, all other things are never held constant. As a general rule, when interest rates are rising most rapidly during an economic expansion, this also corresponds with significant economic growth and increasing corporate profits and generally occurs in the middle of economic expansion phases (as opposed to at their end). Thus, although stock prices are hurt by the higher interest rates through the adverse discounting process, the favorable economic growth and increased per share earnings have, on average, more than offset this negative effect.

Nevertheless, investors should keep in mind that not all industry segments may react in the same fashion. Certain industries carry far higher debt levels than others. As interest rates rise, the carrying costs of these higher debt levels may weigh more heavily on these relatively disadvantaged industries.