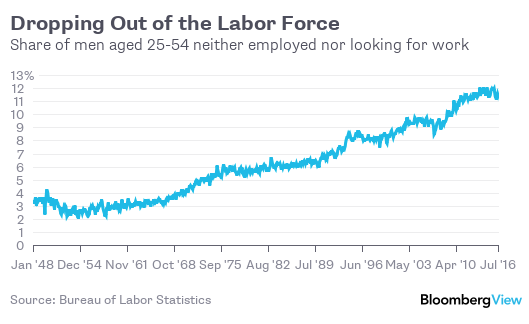

Still, all these survey issues appear to pale in significance beside the real changes in the labor market over the past couple of decades that have made the unemployment rate less informative. Consider, for example, the epic rise in the percentage of prime-age men (ages 25 to 54) who neither have jobs nor have looked for one anytime recently.

In the mid-1950s this was about 700,000 men. In July 1997 it was about 4.5 million. Now it’s around 7 million. Some of these guys are out of the labor force for positive reasons: They’re taking care of kids, they’ve gone back to school, they’ve retired early to take up windsurfing full time. But they’re a minority. As Leonhardt put it in his column back in 2008, just as the labor-force participation rate was beginning to take another big dip:

Instead, these nonemployed workers tend to be those who have been left behind by the economic changes of the last generation. Their jobs have been replaced by technology or have gone overseas, and they can no longer find work that pays as well.

That these people aren’t numbered among the unemployed doesn’t constitute a lie or a hoax—there are good reasons to try to keep the measurement of unemployment consistent over time, and counting labor-force dropouts as unemployed would be a dramatic break from the practice that has prevailed since 1945. But to really understand the long-term health of the job market, there are better places to look than the unemployment rate.