Addictive Behavior

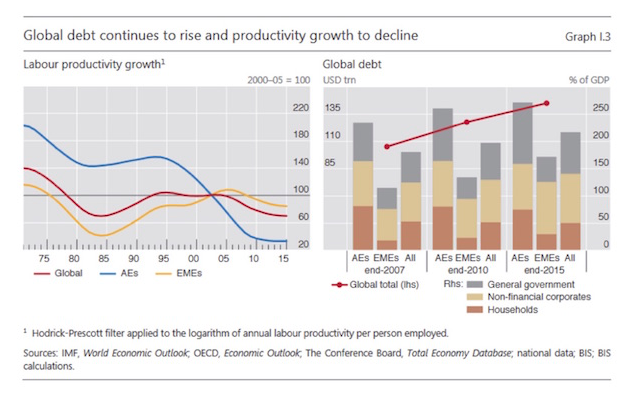

One thing we don’t have to wonder about is the impact of rising debt. The world is just as addicted to debt today as it used to be addicted to OPEC oil. You might think the pace at which we leverage ourselves would be slowing as regulators crack down post-crisis. Not so. Total debt in all categories (except households, whose debt has shrunk only a very little in the advanced economies since 2010) is still growing at a steady clip relative to GDP.

The right-hand chart above shows global debt growing. Pretty much everyone is in hock to someone. Pay down private debt, and government debt goes up. Reduce government debt, and household debt rises. This is what addictive behavior looks like. Forget heroin and OxyContin; debt is the world’s favorite drug by far.

Periodically, addicts concerned about outcomes try to get clean. The results are never pretty at first. Our politicians, unwilling or unable to go through the painful detox process, always go back for another fix. Dealers are always happy to provide. The dealers, in this context, are banks – and central banks more than private ones.

This addiction to debt is one reason we keep having market tantrums. Last year people got concerned about China. Before that it was Greece. Now China is off the radar (even as its currency drops more than it did during our tantrum last summer); and we’re obsessed with the UK, Germany, and Italy. BIS says the results of this oscillating calm and turbulence are troubled equity markets, wider credit spreads, a stronger dollar, and lower long-term interest rates.

Mixed Debt Signals

I noted above that interest rates have an important signaling function. What happens when the signals are wrong? People make bad decisions, of course. And, for at least the last six years (perhaps more), the signals have been very wrong indeed. Distorted signals spurred an epidemic of unwise choices. Worse, many of those bad choices were made by central banks, which, by virtue of their size and position, can spread the infection far and wide. What we have seen is the financialization of business markets, as businesses are incentivized to buy their competitors rather than competing or to buy their own stock with cheap money rather than invest in new productive processes. Neither of those options boosts employment or labor productivity, which is why you see a slowing economy.

Truly “free” markets exist only in theory. Maybe interest rates would find a real equilibrium in a free market, but we can’t know this because our markets aren’t free. What we actually have is a muddled mixture of market forces, political decisions, and human folly.

The BIS report notes the problem with interest rates and suggests that it is at the core of our present predicament. Here’s what they say. (Bold emphasis is mine.)

Importantly, all estimates of long-run equilibrium interest rates, be they short or long rates, are inevitably based on some implicit view about how the economy works. Simple historical averages assume that over the relevant period the prevailing interest rate is the “right” one. Those based on inflation assume that it is inflation that provides the key signal; those based on financial cycle indicators – as ours largely are – posit that it is financial variables that matter. The methodologies may differ in terms of the balance between allowing the data to drive the results and using a priori restrictions – weaker restrictions may provide more confidence. But invariably the resulting uncertainty is very high.

This uncertainty suggests that it might be imprudent to rely heavily on market signals as the basis for judgments about equilibrium and sustainability. There is no guarantee that over any period of time the joint behaviour of central banks, governments and market participants will result in market interest rates that are set at the right level, ie that are consistent with sustainable good economic performance (Chapter II). After all, given the huge uncertainty involved, how confident can we be that the long-term outcome will be the desirable one? Might not interest rates, just like any other asset price, be misaligned for very long periods? Only time and events will tell.

For what it’s worth, I think there is no question that interest rates have been misaligned for quite some time now. When 12 people or 27 people sit around a table and decide what the price of the most important commodity in the world is (that would be the interest rates for money), how can they possibly get it right? The evidence is that, more often than not, they don’t.

But what would happen if the central banks didn’t set rates? Oh dear gods, market participants intone, we would have unrestrained volatility and uncertainty. That is true, but central bank misjudgments about economic trends, translated into interest rates, eventually lead to crashes and result in markets far more volatile than we would experience with lesser, more numerous adjustments that didn’t involve control of rates.

Let’s draw an analogy between monetary policy and forest management. We have learned that by preventing small forest fires we actually create the conditions for large, disastrous fires that are extremely difficult to bring under control. We have found out that we should actually allow the smaller fires in order to avoid the big ones. Unfortunately, the more enlightened approach comes too late for a large portion of our nation’s forests, which in many places have become overgrown tinderboxes. Central bank monetary policy likewise suppresses the smaller corrections that prevent economic conflagrations

I know it is difficult to admit this, but think about it. Can’t stock prices go irrationally low or high? Of course they can. Do they then adjust? Of course they do. We’ve all seen them do it and can point to many examples in market history. So why should interest rates be any different?

We have, all of us, built an economic and political system that encourages and subsidizes debt. Is it any surprise that we have created an excess supply of it? Of course not. There is a great irony here, in that more and more countries are penalizing income and savings – and then we worry about incomes not growing enough. By now, it should be a well-understood concept that if you subsidize and set the price for a commodity (like debt) below its actual market price, you’re going to get too much of it.

Debt is future consumption brought forward. Once debt is incurred, consumption that might have happened in the future won’t happen, and it should come as absolutely no theoretical surprise that at a certain level of debt, growth and income begin to diminish. That is exactly what we are seeing in the real world, even if those who espouse the reigning economic paradigm (Keynesianism) are still in love with their beautiful theory.

There are basically two categories of debt: debt used to purchase or create productive activities (like tools for a carpenter or a new factory for a business) and debt used to consume.

We forget that debt used for consumption doesn’t create new supply; it simply pulls supply forward in time. The problem is that debt can’t do this forever. Pulling your consumption forward to the present means you will consume less later. The BIS says these “intertemporal trade-offs” eventually constrain our options. And when they say “eventually,” what they really mean is “now.” Thus the title of their current report: “The Future Will Soon Be Today.”

Is the Fed Shooting Blanks?

As noted above, the BIS is in the unique position of serving global economic stability in general and central banks in particular. It can criticize central banks more freely than politicians, bankers, or business leaders can. The BIS is usually gently critical in public documents, but I’ve always wondered what happens behind closed doors. I am told by reliable sources that the conversations can get rather blunt, especially in the monthly meetings of global central bankers. The current report ratchets up the public level of the BIS’s concerns.

Right now the problem is that monetary policy is carrying a load it was not designed to bear. Strong central bank action during the crisis was necessary and appropriate, says the BIS report, but the extended wind-down hasn’t served the desired goals. This protracted reliance on extraordinary monetary policy carries the risk of causing the rest of us to lose faith in the policymakers. The BIS has an ominous note on this:

Financial markets have grown increasingly dependent on central banks’ support, and the room for policy maneuver has narrowed. Should this situation be stretched to the point of shaking public confidence in policymaking, the consequences for financial markets and the economy could be serious. Worryingly, we saw the first real signs of this happening during the market turbulence in February.

In other words, what happens when banks, investors, and the public lose trust in the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan? The BIS isn’t talking about the sort of routine grousing we all engage in. Everyone gripes about the Fed in good times or bad. But beneath our chronic irritation, we still maintain a fundamental trust that the Fed will step in to prevent any cataclysmic event. What if that’s not true? What if the Fed really is out of bullets? If you ask almost anyone associated with the Fed, they will tell you they still have choices and ammunition.

The problem I worry about is, do they actually have any more live bullets? I’m quite concerned that in the future they will be “shooting blanks,” and the expected economic responses will simply not happen. The irony is that, like actors in a grade B action movie, they will keep pulling the trigger and shooting those blanks. Somehow, they seem to think the “editing” process will make their economic movie seem more real.

We all hope not to learn the answer to my question. The BIS drops a pretty loud hint, though. With its “Worryingly” sentence, the BIS confirms that we are right to wonder about the continued efficacy of central bank action.

Having worried us about policymaking, the BIS goes on to offer some policy suggestions. They group their ideas into three sections: prudential, fiscal, and monetary.

By “prudential” policy, the BIS means bank regulation and capital requirements. Much has changed on that front since the last crisis. The Basel III framework is forcing banks to hold more capital to cover the risks they take. This requirement is having the effect, according to many traders, of drastically reducing bond market liquidity.

The BIS concedes the point but responds with an argument I haven’t seen anywhere else. Before the last crisis, they say, liquidity was actually underpriced. Liquidity providers, having not been fully rewarded for the value they provide, then disappeared when everyone really needed them. Central banks and governments had to step in and take their place.

To avoid this dynamic in the future, BIS suggests we should be happy to pay more for liquidity than we are accustomed to doing. We should pay market-makers well in good times so they will be there for us when a storm hits.

The best structural safeguard against fair-weather liquidity and its damaging power is to avoid the illusion of permanent market liquidity and to improve the resilience of financial institutions. Stronger capital and liquidity standards are not part of the problem but an essential part of the solution. Stronger market-makers mean more robust market liquidity.

I deeply suspect this language is really a veiled criticism of high-frequency algorithmic trading. High-frequency trading (HFT) creates an illusion of liquidity. Depending on whom you choose to believe and how you measure it, HFT may be 70% or more of total market volume. This trading will immediately disappear if we actually need liquidity. It is simply a canard foisted on the public by exchanges and funds that use HFT to say that these entities are providers of liquidity. HFT is precisely what the BIS is talking about when they use the term illusion of market liquidity.

It makes me wonder if we are going to miss the “specialist” role the NYSE has traditionally had for the trading of most listed stocks. The exchange has nearly done away with all that and thought it could make up for the lost fairness and market equilibrium with volume. I’m not sure it has worked out that way.

In the fiscal policy area, the BIS says we should rethink how we evaluate sovereign risk. Because governments – or at least the ones that have their own currency – can always “print money,” investors assume their credit risk is low or nonexistent. That’s clearly not the case. Ask someone who invested in Argentine government bonds a few years ago, and they will explain.

Whatever governments deliver in reduced credit risk usually gets offset by higher inflation and interest-rate or market risks. We need to think about risk as a liquid substance. We can move it from one bottle to another, split it among multiple bottles, or put it in the deep freeze, but we can’t make it disappear. Even pouring it down the drain just transfers it to someone else.