Click here to read the Views From The Experts.

As a result of recent global economic expansion, successful individuals frequently control wealth and earn income in numerous countries around the world. When such individuals want to become active in philanthropy, they are faced with many choices. They might want to give to operating charities in myriad fields in almost every country, but gift or inheritance taxes in the contributor’s home country may apply. Not infrequently, they want to fund an organization they can control, which can then fund other charities and charitable causes in their home countries and overseas.

When that is the objective, where in the world should the grant-making foundation be formed to provide the greatest degree of flexibility and maximize the tax advantage? What structure or legal entity is best, and what rules will govern its grant-making activities?

The answers to these inquiries must take into account several more specific practical questions in each country considered:

• How difficult or expensive is it to form and qualify a charity in a given country?

• What types of legal entities are generally used?

• To what extent can the principal individual providing funding (call him or her the “donor”) or a family member be a director, trustee, employee, contractor, vendor or paid service provider to the charity?

• Are there annual filing requirements?

• Will the donor’s involvement be publicly disclosed?

• Are there investment limitations?

• Will the charity be subject to the country’s income tax?

• Will the donor’s contributions to the charity provide a tax advantage and avoid tax charges?

• What fields may the charity support in the country?

• Can the charity make grants to charities and charitable causes in other countries?

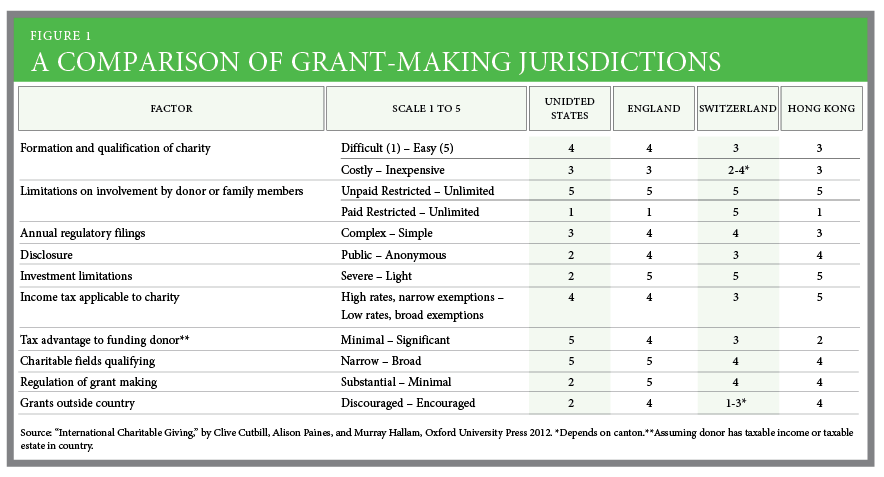

These questions should be directed to a donor’s expert counsel. When I’ve been asked to advise in such situations, I use a detailed table I’ve assembled that compares the legal advantages of different jurisdictions. A complete comparison is not possible here, but to simplify, I will limit the discussion to grant-making, non-operating charities formed in four frequently considered locations: the United States, England, Switzerland and Hong Kong (the last is an autonomous territory rather than a country, but the distinction is unimportant here; I refer to England instead of the United Kingdom because the rules may differ in Scotland and Northern Ireland; and the generic reference to Switzerland must take into account that every Swiss canton has its own rules for charitable foundations).

For each of the factors examined, I have ranked the locations on a rough scale of 1 to 5 (with 5 being the best).

Those restrictions in Hong Kong and the United States leave England and Switzerland as generally more friendly jurisdictions to charities making grants outside the home country. Still, England has requirements that grantors exercise reasonable due diligence, and some Swiss cantons also have local-benefit rules for charities. So even in those jurisdictions, international grant-making should be approached with care.

It’s safe to say that grant-making charities in the United States are more heavily regulated than those in the other countries. The U.S. has minimum distribution rules, net investment income tax, self-dealing restrictions and requirements for the public disclosure of annual tax returns (including the reporting of compensation paid to insiders and the reporting of donor identity and contribution amounts). Compare those rules with those of England, which makes no distinction between private foundations and operating charities. Of the four jurisdictions we’ve discussed, only the U.S. requires grant-making charities to disburse a minimum percentage of their assets’ value per year, and only the U.S. imposes additional requirements (beyond reasonable due diligence) on overseas grant making.

The United States is, however, fairly attractive for the income tax advantages it offers to charities and donors. And while the U.S. does not offer a complete tax exemption for investment income generated from a charity (as other countries do), the actual net-investment income tax in the United States (1% to 2%) is not enough to seriously deter most donors choosing a jurisdiction. Nor does Switzerland’s 4% federal income tax seriously dampen its attractiveness.

The U.S. also allows donors a deduction limit of 30% of adjusted gross U.S. income and the excess can be carried forward for five years. Switzerland’s limit is only 20%, and there’s no deduction for the excess. In the U.S., England and Switzerland, meanwhile, a donor can get tax breaks for donating publicly traded securities, something not allowed in Hong Kong, which allows deductions only for cash (Hong Kong, however, may offer stamp duty relief on transfers of stock and, in any event, capital gains may not be taxable in Hong Kong, which has a relatively benign territorial system of tax).

England’s system, with its so-called “gift aid” and “share aid,” offers tax advantages for donors similar to those in the U.S., but only for contributions of cash, publicly listed securities and real property (more on this below). There is no tax advantage for contributions of other assets. By comparison, the U.S. allows a deduction for most appreciated assets other than publicly traded securities in an amount equal to the donor’s tax basis in the asset.

When it comes to contributions of real estate, Switzerland provides a deduction based on the market value of the property; England does the same, but only if the real estate is located in the U.K. The U.S. limits the deduction to the donor’s basis for a gift to a private foundation. As noted before, Hong Kong provides no deduction for non-cash contributions.

The U.S., England and Switzerland (at the canton level) have an inheritance tax against which bequests to charity are deductible or exempt. Hong Kong has no inheritance tax, so there’s no tax advantage in avoiding the territory. In fact, its relatively low tax rates mean that most charitable giving done there is not primarily motivated by tax relief.

Of the four jurisdictions, only the United States allows tax relief for charitable contributions accomplished via split-interest trusts that provide a financial return to the donor or the donor’s family.

But if tax relief is the main issue, it’s only relevant if the donor has taxable income in the country in which the foundation is qualified, or an estate that will be subject to inheritance tax in that country. Thus, the donor who has income and assets only in the various countries of Europe will generally not find tax relief with a grant-making charity in the United States or Asia. Moreover, because a charity formed in another country will most likely not be qualified in the donor’s home country, a gift to that charity may trigger a tax charge under the home country’s gift or inheritance tax, as is the case in England. This trap may also catch the unwary donor who contributes to overseas operating charities. Where charitable tax relief is immaterial to a donor, the choice of jurisdiction is considerably widened, and certain “offshore” jurisdictions may be attractive to those seeking a light-touch regulatory regime.

One useful strategy is to create a “dual-qualified” structure. In such a case, a charity formed in the United States creates a subsidiary in Hong Kong or the U.K. and structures the subsidiary so that it will qualify as a charity in those countries yet be treated as part of the U.S. charity for U.S. tax law. This structure is particularly beneficial where a donor is subject to tax in both the U.S. and England or in both the U.S. and Hong Kong, since it gives the donor income tax benefits in two countries.

In the end, picking the right jurisdiction is more like judging a figure skating competition than doing your arithmetic homework; my number rankings should not obscure the fact that the final choice is more art than number crunching. Reasonable minds may disagree about the country factor rankings—nor will two philanthropic individuals agree on what factors are relevant to them, and they will certainly weigh the factors differently. Clearly, consultation with expert legal counsel is essential.