The Federal Reserve looks to have outsourced monetary policy to the financial markets -- and that may not necessarily be bad.

Fed Chair Janet Yellen told the Economic Club of New York on Tuesday that policy makers had scaled back the number of interest rate increases they expect to carry out this year after investors did the same.

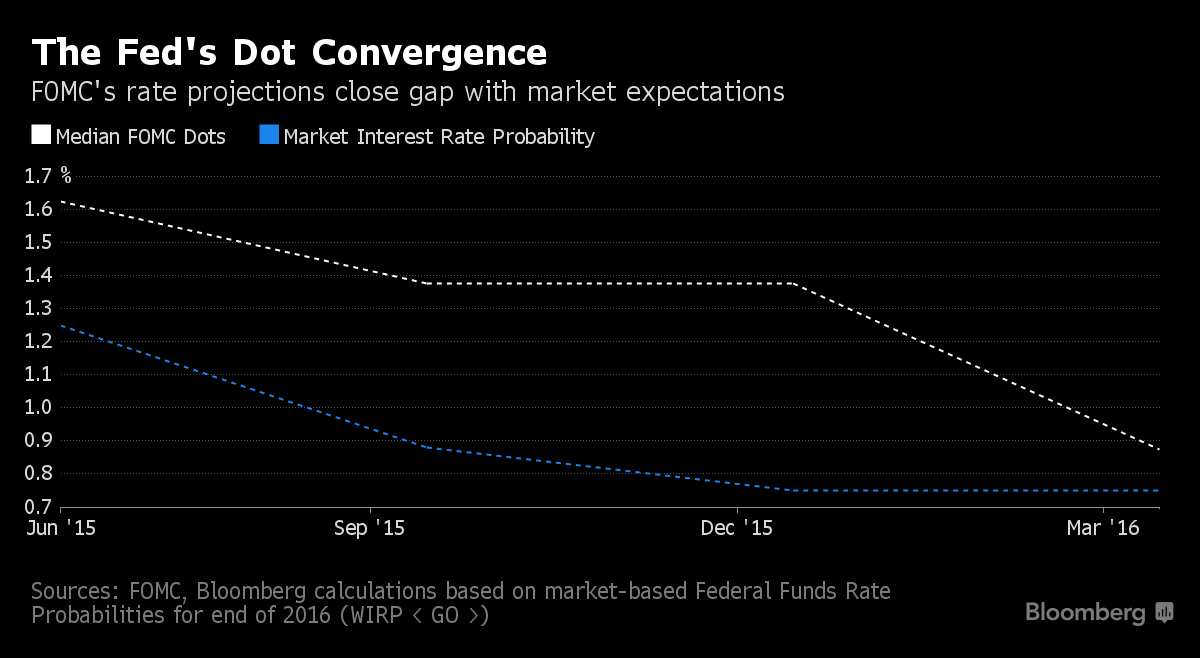

She argued that the downgrading of rate expectations in the market had led to lower bond yields, providing the economy with needed support in the face of weaker growth overseas. The Fed then followed suit this month by reducing its anticipated rate hikes in 2016 to two from four quarter-percentage point moves projected in December.

“That’s a good thing,” said Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP LLC in Jersey City, New Jersey, commenting on the sequence of actions. “Monetary medicine gets into the blood stream faster if the public can anticipate what the Fed’s response to an economic shock will be.”

There are pitfalls. Investors may become so impressed with their ability to influence Fed policy that they’ll press for more stimulus than the central bank is willing to supply.

Forcing Fed

“The risk is that markets’ perception of such continued accommodation will embolden them even more to try to force the policy hand of the Fed,” Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz SE and a Bloomberg View columnist, said in an e-mail.

Indeed, investors in the federal funds market are betting that the central bank will raise rates just once this year, not the two times policy makers envisage.

The Fed’s experience over the last six months also shows how difficult it can be for the central bank to align investors’ view of optimal monetary policy with that of its own.

“It’s a constant learning process by both the Fed and the markets,” said Joachim Fels, global economic adviser for Pacific Investment Management Co., which oversees $1.43 trillion in assets.

Yellen acknowledged that the policy-making Federal Open Market Committee and investors might not always see eye-to-eye. “In such situations, the Committee must do what it believes is appropriate while clearly explaining the rationale for its actions,” she said in a footnote to her speech Tuesday.

‘Automatic Stabilizer’

Yellen used her spoken remarks though to extol the symbiotic relationship between the central bank and the financial markets. “This mechanism serves as an important ‘automatic stabilizer’ for the economy,” she said.

Her comments come against the backdrop of continued criticism from Republican lawmakers and economists that the Fed is following a discretionary monetary policy that investors don’t understand and is hurting the economy as a result. They want the Fed to follow a monetary policy rule, such as the one espoused by Stanford University professor John Taylor. It uses a simple equation to link changes in interest rates to movements in inflation and the economy.

With her remarks on Tuesday, Yellen was “implicitly defending the Fed’s approach in the rules versus discretion debate as being one that’s systematic” and understood by the markets, Crandall said.

‘Ideal World’

It’s an “ideal world” when central bankers and financial market participants are in an sync on how monetary policy should respond to incoming economic data, said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York. In that case, “the expected path of policy rates should adjust before even the Fed moves.”

Unfortunately, “we haven’t gotten to that point,” Feroli added -- in spite of Yellen’s embrace of the market’s latest moves in her speech.

Case in point: The ups and downs of asset prices over the last half year as investors have tried to adjust to what Washington-based Cornerstone Macro LLC partner Roberto Perli said were seemingly big and frequent changes in the Fed’s stance.

Yellen and her colleagues surprised many investors last September when they decided not to raise rates from the near zero percent levels that had prevailed since 2008. Policy makers then switched their stance in October by clearly signaling that a rate hike was imminent, before moving in December.

Financial Turbulence

The rate increase -- the first in nine years -- at first went off smoothly. The financial markets though turned turbulent in the new year after China allowed a small depreciation of its currency, fanning fears of a bigger devaluation to come. Uncertainty about the Fed’s plans also fueled the turmoil as investors increasingly questioned the interest rate path set out in the central bank’s so-called dot-plot.

One problem: The central bank’s quarterly rate forecasts -- arranged in little circles representing each Fed officials’ projection for the appropriate level of the benchmark federal funds rate -- become stale as new data arrive.

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, a voting member of the FOMC this year, said in a Bloomberg interview last week that the rate projections contribute to uncertainty among investors.

Fels said Yellen’s effort to get the Fed’s message over to markets also is complicated by the cacophony of voices from within the central bank itself opining on policy and the economy. “There are quite a few people commenting and the message is not often the same,” he said. Bullard said on March 24 the next rate hike “may not be far off,” and other Fed officials have also pointed to the possibility of an April move.

In the end, the Fed chair’s willingness to outsource monetary policy to the markets will probably come down to whether she agrees with how investors are responding to changes in the economy. It might be a case of “validating the market when it’s telling you what you may have been leaning toward anyway,” Feroli said.