In Jackson Hole, Fed Chair Janet Yellen was not expected to speak much about the current economic outlook or monetary policy. In line with the general theme of the Kansas City Fed’s symposium, she did talk about the Fed’s monetary policy toolkit. However, she went out of her way to preface that discussion with “a few remarks on the near-term outlook for the U.S. economy and the potential implications for monetary policy.” She delivered a strong hint that the Fed is close to raising short-term interest rates. The market reaction was initially disbelief.

First, let’s set the backdrop for Yellen’s speech. Recall that the FOMC, in its July 27 policy statement, had seemingly paved the way for a possible September rate hike, by noting that “near-term risks to the economic outlook have diminished.”

Prior to 1994, the discount rate (the rate that the Fed charges banks to borrow short term) was the Fed’s main policy level (prior to that, the FOMC did not announce changes to the federal funds target rate). Unlike the federal funds rate (the market rate that banks charge each other for overnight borrowing), which is set by the Federal Open Market Committee (the five Fed governors, the New York Fed president, and four other district bank presidents who rotate once a year), changes to the discount rate are requested by one or more of the district banks and are approved (or not) by the Fed’s Board of Governors. Typically, if an increase in the discount rate is deemed warranted, the governors will raise it at the same time that the FOMC increases the federal funds target rate. The BOG met on July 25 (just ahead of the July 26-27 FOMC meeting) to consider requests to raise the discount rate. Eight of the twelve district banks had requested an increase. The presidents of four of those banks have a vote on the FOMC this year. The BOG will meet again on August 29 to consider changes to the discount rate (but no change is expected).

In the last week or two, New York Fed President Dudley said that “we are edging closer towards the point in time when it will be appropriate to raise rates further,” adding that a September move “is possible.” Fed Vice Chair Stanley Fischer, the grand old man of monetary policy (having taught former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke and ECB President Mario Draghi), said that “we are close to our targets (of price stability and full employment).”

Speaking about the current situation, Yellen said that “while economic growth has not been rapid, it has been sufficient to generate further improvement in the labor market.”

“Looking ahead, the FOMC expects moderate growth in real GDP, additional strengthening in the labor market, and inflation rising to 2 percent over the next few years. Based on this economic outlook, the FOMC continues to anticipate that gradual increases in the federal funds rate will be appropriate over time to achieve and sustain employment and inflation near our statutory objectives. Indeed, in light of the continued solid performance of the labor market and our outlook for economic activity and inflation, I believe the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months. Of course, our decisions always depend on the degree to which incoming data continues to confirm the Committee's outlook.”

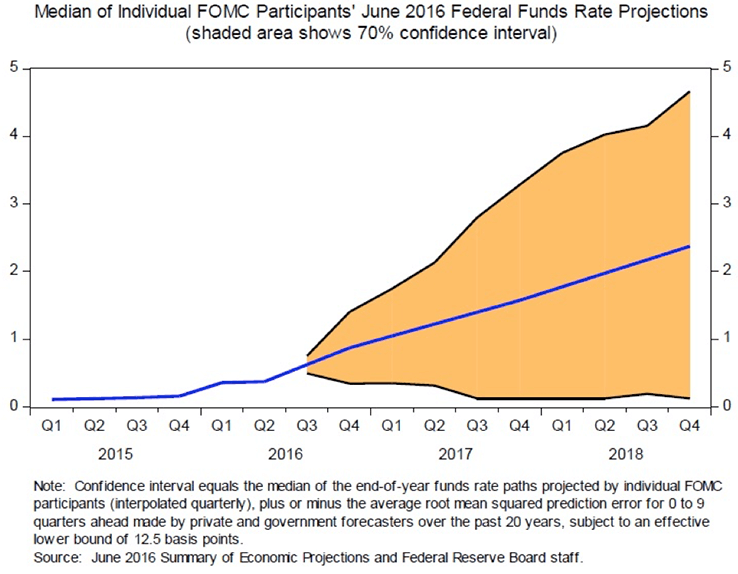

Yellen noted that “as ever, the economic outlook is uncertain, and so monetary policy is not on a preset course. Our ability to predict how the federal funds rate will evolve over time is quite limited because monetary policy will need to respond to whatever disturbances may buffet the economy. In addition, the level of short-term interest rates consistent with the dual mandate varies over time in response to shifts in underlying economic conditions that are often evident only in hindsight.” Fed mid-June officials’ projections of the appropriate path of the federal funds target rate vary widely. Yellen said the wide range is because “the economy is frequently buffeted by shocks and thus rarely evolves as predicted. When shocks occur and the economic outlook changes, monetary policy needs to adjust. What we do know, however, is that we want a policy toolkit that will allow us to respond to a wide range of possible conditions.”

The Fed played a critical role in stabilizing the economy following the financial crisis, but public opinion surrounding the central bank has been decidedly poor (largely reflecting a lack of understanding of what the Fed can do). Monetary policy cannot solve all of the economy’s problems. It is ill-suited to address the slowdown in productivity and the widening in income inequality. There were protests for “a people’s Fed” in Jackson Hole and Fed officials did meet with community activists. A rate hike in September would raise borrowing costs a little, but the Fed would see a greater good in promoting financial stability.

Scott J. Brown, Ph.D., is chief economist at Raymond James & Associates.