"Do unto others as you would have them do unto you" is often referred to as The Golden Rule. It can be found in many cultures and dates back to early civilization. It is an ethic of reciprocity that underlies the modern concept of human rights. It is a standard to which most advisors would aspire.

However there is a danger here. Clients often ask "What would you do in my situation?" How we answer this question is important. The direct answer to "What I would do ..." is not the correct answer, as most of us know, because what is right for us is not necessarily right for our client.

This is particularly so when it comes to the amount of risk someone should take. Early in my career I thought I knew how much risk my clients should take. For any given situation, I considered the pros and cons carefully and came up with the logical answer. (I did, after all, have a degree in mathematics.) What I didn't realize at the time was that I was basing my views on my values without realizing that these were not necessarily my clients' values. In my defense, I was in my early twenties, as were my clients, and we were facing similar decisions about life. I would like to be able to say that I saw the error of my ways unaided. But, in fact, it was a client, a young doctor training to be a psychiatrist, who persuaded me that there was no one right answer for everyone. Initially, this was somewhat of a disappointment, but I soon realized that it actually presented a fascinating challenge.

So I began to talk to my clients about their risk tolerance. There was no particular structure to these discussions. I asked a mix of open and closed questions, usually not the same questions nor in the same sequence. Sometimes, in my ignorance, I even included questions about physical risk-taking. I kept the discussion going until I felt I could categorize the client. I considered myself a "Moderate" and, perhaps not surprisingly, most of my clients finished up as Moderates. I did realize that I could 'guide' the discussion and tried to avoid doing that, but with what success I'm now not sure.

Several years later, when there were six advisors in our firm, we acknowledged that no two of us did the risk tolerance discussion in the same way. One of my partners and I spent a morning developing a risk tolerance questionnaire that we all then used. My clients were still mainly Moderate, and overall our clients were mainly Moderate, but one advisor seemed to have mainly Conservative clients and another mainly Aggressive clients. We recognized that this was probably due to the way that the questionnaire was explained rather than that as groups these clients were different, but apart from "counseling" them we couldn't think of what else to do.

I eventually sold out to my partners and after an extended sabbatical became involved in what is today FinaMetrica. Early on we discovered that there was a scientific discipline, psychometrics, for measuring constructs such as risk tolerance. In the process of developing our test we enlisted the aid of several financial planning firms, including my old firm. We asked advisors to ask their clients to complete risk tolerance questionnaires to provide us with a sample upon which we could do the required statistical analysis. To control for the possibility of bias between those clients who completed the questionnaire and those who didn't, we asked the advisors to estimate their clients' risk tolerance before they asked them to do the questionnaire. In the event, we discovered no evidence of bias but we did discover that the advisors' estimates, including those from my old firm, were highly inaccurate. Here it should be noted that these were experienced advisors and established clients. So inaccurate were the advisors' estimates that it would have been better if they had made no attempt to assess risk tolerance and simply assumed that all clients were average. And this is not an isolated instance; all the studies of which I am aware demonstrate similar inaccuracy in advisors' estimates of their clients' risk tolerance .

This was a somewhat disconcerting discovery for me. I had thought that in my time as an advisor I had done a reasonable job of assessing my clients' risk tolerance; however the evidence suggested that this was probably just overconfidence on my part. I did take some consolation from the fact that I had assessed most of my clients as Moderate so I was probably reasonably accurate most of the time. But I wondered about the two advisors at my old firm: one whose clients all seemed to be Conservative and the other whose clients all seemed to be Aggressive.

From the data we were collecting as advisors used our risk profiling system with their clients, we discovered that advisors' clients were marginally more risk tolerant than the public and that advisors were significantly more risk tolerant than their clients. The latter indicated to us a potential danger. If advisors did not make accurate estimates of their clients' risk tolerance and the advisors were significantly more risk tolerant than their clients, a here's-what-I-would-do-in-your-situation mindset would very likely lead to clients being overexposed to risk.

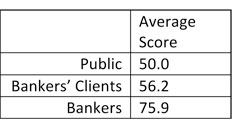

Late last year we came across an extreme sample of this danger. As part of an exercise we were doing for the Sydney office of a private bank, we tested 18 bankers and 452 of their clients. Our test scores on a 0 to 100 scale, mean 50 and standard deviation 10. These are the average scores we obtained.

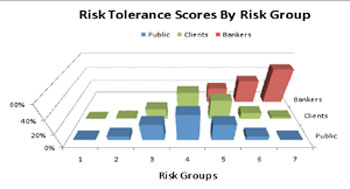

This group of clients is more risk tolerant than clients generally but the bankers are still nearly a standard deviation more risk tolerant than their clients. When we look at how the scores are distributed we see the risk groups are a standard deviation wide. They can be thought of in terms of the standard clothing sizes-Medium, Large, Small, Extra Large, etc. As can be seen, 50% of the bankers are in Risk Group 7. This is at least two and a half standard deviations above the mean-think XXXL. However, only 3% of their clients and 1% of the public are in Risk Group 7.

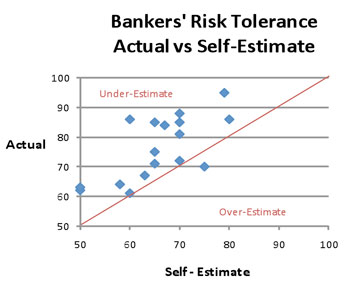

But surely the bankers know they are XXXLs? Perhaps not. The last question in our questionnaire asks respondents to estimate their score. Here are the bankers' scores with their estimates of what their scores would be.

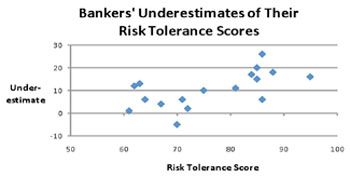

All but one underestimated and some of the underestimates were substantial. As can be seen below, there is a clear trend: the higher the risk tolerance, the greater the underestimate the average underestimate was 10.2 and the largest was 26-a banker who scored 86 but estimated his score would be 60, i.e. an XXL who thinks he's an L.

Needless to say, management at this private bank was alarmed by the findings. They could see the danger in having a group of bankers who didn't recognize that they were highly risk tolerant advising clients who, while more risk tolerant than average, were significantly less risk tolerant than their banker.

Admittedly, this is one case. However, we do know that advisors generally are more risk tolerant than clients and don't realize how risk tolerant they are. If I was back in my advisor days, knowing what I know today, the least I would do is test my own risk tolerance and that of a sample set of my clients. If my perceptions were proved accurate I could sleep comfortably knowing that I had been doing the right thing by my clients ... which is, after all, the promise we all make to our clients.

Geoff Davey is cofounder and director of FinaMetrica and the developer of the FinaMetrica risk profiling system. Prior to FinaMetrica he was one of the pioneers of financial planning in Australia. For more information on assessing risk tolerance, visit www.riskprofiling.com.