It is going to happen. At some point, a retiree's current withdrawal rate will be too high for a retiree's or his planner's comfort level. If 4% is a safe initial rate, it is reasonable to think that a current rate of 5% or 6% is less safe and at some level the current rate is outright unsafe.

On the other hand if a current withdrawal rate is very low, a retiree is not utilizing as much money as he could. Such a retiree could be spending more on himself or on others he would like to benefit. There is a lifestyle opportunity cost to being too conservative, but many clients seem to have a hard time viewing that as a problem. Instead, most clients worry about running out of money from spending too much and advisors tend to view avoiding depletion as a central objective of their work.

The current withdrawal rate is the amount of the withdrawal for the current year divided by the portfolio value at that time. The current withdrawal rate goes up because of either an increase in the withdrawal amount, a decrease in the portfolio value, or a combination of the two. We have some control over spending amounts but little control over markets, so most discussion tends to center on when one needs to reduce their spending.

When is a current withdrawal rate too high? The answer is debatable, but I have seen regularly three methods among peers--referring to a historical matrix of outcomes, stochastic modeling to establish confidence intervals, and decision rules. All three essentially set bands around an initial withdrawal rate to indicate when spending cuts or raises should be considered. If the current rate exceeds the top end of the band, cuts are considered. If the rate goes below the lower band, increased spending may be a viable option for a client.

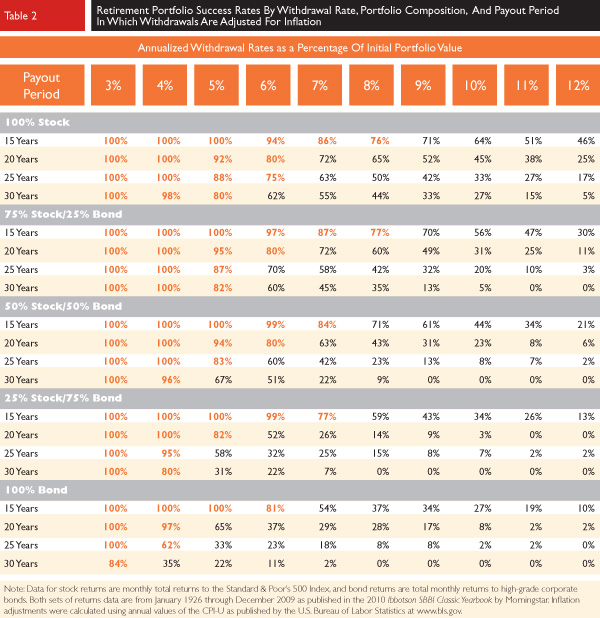

The matrix method requires no software and can be an excellent discussion tool for clients because it can present the basic tradeoffs involved in managing money through retirement in a digestible portion. One simply compares various success rates described by the matrix to the current situation. Typical metrics for the matrix are time frame, a portfolio allocation, and a range of spending rates. I've seen this in a number of studies, most recently in the Journal of Financial Planning, April 2011.

In "Portfolio Success Rates: Where To Draw The Line," Cooley, Hubbard, and Walz suggest that as long as the applicable success rate exceeds some minimum, it is probably OK to make no alterations. For instance, consider a client who is sufficiently comfortable with uncertainty that he seeks a minimum success rate of 75%.

The matrix shown from the paper suggests an initial inflation-adjusted withdrawal rate in excess of 5% for a 75/25 stock/bond mix and a 30 year time frame since the corresponding success rate has been 82% under those parameters. It would also suggest that for a client whose time frame was 15 years, the current withdrawal rate could go as high as 8%.

Where to draw the line is debatable, but in my experience, most clients want at least an 85% success rate and very few have the risk tolerance, risk capacity, or flexibility in their spending to accept a rate below 75%.

You will also find software packages that utilize Monte Carlo simulation and/or bootstrapping techniques to assess the odds of success at a given point. Financeware is possibly the most widely used since a number of large brokerage firms employ their technology. It establishes a zone of acceptable success rates. If the probabilities drop below a certain level, changes are suggested to improve the odds of success and if the success rate is too high it prompts the client to consider the effect on their lifestyle. The word "sacrifice" is used to describe the condition where spending relative the portfolio size is low.

A similar type of framing could be adopted with the output of other software packages. If the success rate drops to low, or rises too high, consider taking action. In my practice, I usually start with a matrix and move on to software for more precise modeling. These days, I can sketch a basic matrix and illustrate the interplay between allocation, withdrawals and time frame on a napkin. The concepts of the tradeoffs involved can be made that simple.

Regardless of whether one uses a historical matrix or software with stochastic modeling, and regardless of what success rate is deemed acceptable by client and advisor, a retiree will face the issue of what exactly should be done when the current withdrawal rate is too high (success rate is too low). This is where decision rules come into play.

One of the better-known viewpoints on this subject comes from Jon Guyton of Cornerstone Wealth Advisors Inc. in Minneapolis. He followed up his original "perfect storm" work with a paper, co-authored with David Klinger, that used stochastic analysis to further explore the issue. This 2006 paper kept much of Guyton's original decision rules intact but added two new rules relevant to our discussion. The "capital preservation rule (CPR)" and the "prosperity rule (PR)," both speak to the issue of a trigger to modify spending and a specific amount for the modification.

The CPR holds that when a current year's withdrawal rate-using the decision rules in effect-has risen more than 20 percent above the initial withdrawal rate, the current year's withdrawal is reduced by 10 percent. The other decision rules in effect are then applied to this decreased withdrawal amount.

The PR holds that in years with a withdrawal rate more than 20 percent below the initial withdrawal rate, the current year's withdrawal is increased by 10 percent. The other decision rules are then applied to this increased withdrawal amount.

The paper describes the confidence levels applicable to sustaining an initial withdrawal rate and the probability of maintaining purchasing power over a 40-year period. Anytime cash flow is cut, frozen or increased slower than the inflation rate, that action extends portfolio life over a cash flow stream that always increases with inflation at the expense of losing purchasing power. The prosperity rule helps make up for this loss when markets are favorable or spending is modest.

The result of Guyton and Klinger's analysis showed that by not insisting that a cash flow increase in lock step with inflation and employing the decision rules, initial withdrawal rates well above 4% were likely to survive the 40-year period and preserve purchasing power.

The most practical takeaways from the discussion about current withdrawal rates in my view are 1.) There is no such thing as set it and forget it. It is a near certainty that it is a matter of when their withdrawal rate prompts an adjustment not if. 2.) Some equities are a necessity for a most retirees due to the time frames. Cooley, Hubbard and Walz put the success rate for a 4% initial rate over 30 years for an all bond portfolio at a mere 35% and Guyton/Klinger's minimum equity allocation was 50%. 3.) It is recommended that you determine with clients exactly what clients will need to do when triggers are reached.

This last point is particularly important. There were no scenarios in the Guyton/Klinger paper where the CPR (10% cut) was not invoked. With the need for equity in the portfolios and 20% declines in equity markets occurring on average every five years, spikes in the withdrawal rates will be frequent. Further, scenarios cited involved anywhere from 13 to 24 incidents of cash flow changes (cuts, freezes, and raises) over the 40-year periods.

We financial planners can get buried in the mathematics imbedded in our spreadsheets and software packages and find great fascination with studies of sustainable portfolios but our client's success is most likely to hinge on what clients actually do when things change. Things always change.

I see more and more planners instituting spending policies for their clients. I wish to encourage wider spread development of these policies. The studies show a variety of ways that the odds of success can be boosted but this only happens in real life if the appropriate action is taken. The more collaborative with the client the development of these policies is, the more meaningful to the client they become and the more likely they are to be followed. If clients do not take the proper action when needed, they will not benefit from what these studies tell us.

This column focused on the actions relating to changes in withdrawals. The withdrawal rate is also a function of portfolio size and therefore market and investor behavior. I'll dive into some of those issues next time. That's a whole other kettle of fish.

Dan Moisand, CFP has been featured as one of the America's top independent financial advisors by most leading financial advisor publications. He has spoken to advisor groups on five continents on topics such as managing investments and navigating tax complexities for retirees, retirement readiness, and most topics relating to the development of the financial planning profession. He practices in Melbourne, FL. You can reach him at 253-5400 or [email protected]