A key risk objective for advisors is to prepare their clients for different outcomes, so they are pre-armed in terms of expectations and planned responses. We know that the market is not going to progress smoothly. There will be bumps in the road, negative and positive, whether from economic fundamentals, periods of “irrational exuberance,” tax and regulatory changes, or geopolitical shocks. Understanding that such scenarios are likely to occur at points along the client’s journey helps the client temper the reflexes of fear and greed that afflict many investors.

Coach Clients To Become Market Pros

The client can approach those inevitable disruptions with the perspective ... and behavior ... of a pro: “Yeah, I’ve seen this movie before; I know what to do” rather than overreacting to events in the moment. Both the advisor and the client already have a plan for what to do ... and what not to do.

This is especially important if a disruptive event occurs late in that journey, with little time remaining for recovery. For example, the global financial crisis of 2008 saw many portfolios decline nearly 50%. Recovery was fast, in historical terms, but it still took several years to accomplish. If clients panicked, as some did, and “cut their losses” by greatly reducing their risk/return postures in March of 2009, that total “recovery” has still not arrived.

Effective advisors help clients manage the risks from these critical events by rehearsing future possible scenarios: “what if” exercises that move the discussion outside the frame of everyday ups and downs of the market and into the realm of market dislocations that could be truly significant for the client.

These scenarios are more than numbers; they are narratives of how things might unfold, how they might progress over time, with the host of uncertainties and market effects. This is what a client wants to know, and what is needed to assess the implications for the specific client. It is what is needed to provide a personalized discussion based on the client’s interest and financial expertise, on the specifics of their portfolio, risk tolerance and risk capacity, as well as where they currently are in achieving their financial goals. This means looking at scenarios in the context of how long they might take to resolve, what parts of the markets will be most affected, and how bad (or good) the scenario might be.

It Was The Most Bullish Of Times, It Was The Most Bearish Of Times ...

To understand how a scenario is a narrative, think of it like a novel, a story that drives forward with twists and turns. A scenario has an opening chapter with the event that gets the action going; it has the current market environment as its setting. It has a main character that threads itself through the story plotline, tracing out the path of the relevant markets as the scenario gathers force and then dissipates. And just like novels, potential negative scenarios rest within various genres. Those might be driven by overstretched fundamentals, by market forces of leverage and illiquidity, by the macro cycles of recession, and by non-economic shocks like geopolitical instability.

To start building a scenario we identify the catalyst event, the “what if.” And we do this avoiding the shotgun approach of listing everything under the sun. Doing that is not very helpful; risk management has to be more than, “Be careful, anything could happen.” In fact, at any given time there are probably only a handful of material events to consider when building scenarios. Still, there can be market disruptions that seem to come out of nowhere, so astute advisors will want to consider the ill-defined “black swan” event, just in case.

Three Elements Of A Solid Scenario

A scenario is dynamic and multi-dimensional. A well-specified scenario, one that is open for a narrative, has three components:

First, there is a cloud of uncertainty around the impact an event might have on the market. The consequent market movement is uncertain, and will vary based on the vulnerability of the market. Without understanding the market environment, we can’t get a good read on the market implications of a scenario.

So once we have determined the type of scenario, we need to put it into the current market context, adjusting its magnitude for the current market reality. Unfortunately, almost all of the current approaches for projecting forward risk use historical returns. For these, the assessment of risk will only be useful insofar as the future is reflected in the past. But there can be no certainty about that. The obvious remedy for this weakness is to look at the market now rather than in the past, to include current market data in the development of scenarios. For example, if there is more leverage or concentration in the market than in the past, it will be more vulnerable. The leverage will amplify any need to sell, and the concentration will lead there to be more investors running for the door.

Second, a scenario does not affect “the market” uniformly. Depending on what occurs, different parts of the market, different risk factors will bear the brunt of the effect. In order to understand how a specific portfolio will evolve under a scenario, we must look at the underlying risk factors.

To see the important risk factors, consider one scenario of growing current concern: inflation. Companies with high leverage will be at high risk because many may need to refinance at a higher interest rate. Similarly, smaller companies will be at higher risk because they tend to have less bargaining power to pass on their rising costs.

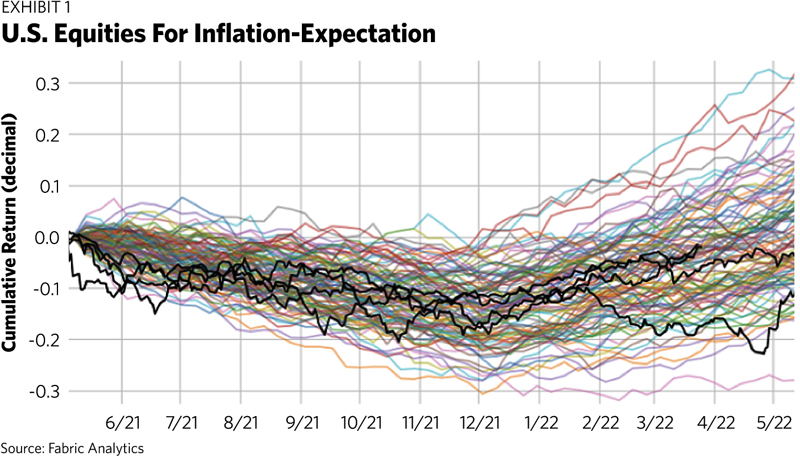

Third, the event does not occur in one fell swoop. It follows a course over time: the time to the bottom ... or top, the time to the recovery. So the scenario should reflect possible responses over time. As an illustration, we show an ensemble of 100 of these possible realizations of how the U.S. market, as represented by the S&P 500 index, might respond in an inflation scenario.

Toward the top are possible paths where the event occurs and its effect fizzles, at the center of mass the educated best guess of the most likely path based on the historical investigation, and toward the lower part are the cases with a large impact. Advisors need to be able to discuss with clients the range of possible worlds, so to speak, that might develop over time. Not one number for a market drop, for example, and not even just the distribution of that drop, but also the time dimension for how the scenario might unfold.

Forewarned Is Forearmed

This scenario-based rehearsal of the ebbs and flows of investment markets is crucial since it not only affects clients’ actual financial prospects but also their willingness to take further risks. As advisors, we serve our clients by providing a “pre-mortem” of material events that might occur and how those could affect their portfolio and consequently how they affect attaining their goals. We use scenarios as a prime tool for doing this, scenarios framed in terms of a narrative that engages the client’s rational decision-making and that helps to overcome overly emotional responses.

Rick Bookstaber is co-founder and head of risk at Fabric. He previously held chief risk officer roles at Morgan Stanley, Salomon Brothers, Bridgewater Associates, and the University of California Regents and served at the U.S. Treasury in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. He is the author of The End of Theory (Princeton, 2017) and A Demon of Our Own Design.

Tim Kochis is advisor to and an investor in Fabric. He is co-founder and former chair and CEO of Aspiriant. He previously led personal financial planning at Deloitte & Touche and Bank of America. He co-founded the Personal Financial Planning program at UC Berkeley and has written several books, including Managing Concentrated Stock (2d Ed. Bloomberg, 2016).