Clients will be asking you about 2019 Roth conversions as the year winds down. They’ll want to know if they should convert their IRA to a Roth IRA, how much should they convert, and most important, how much will it cost?

What will you tell them?

You’ll need to know how to accurately project the tax cost of a 2019 Roth conversion because once the conversion is done, it cannot be undone. Roth conversions can no longer be recharacterized, so once the funds are converted, the tax bill is set in stone. You have one chance to get this right for the client, so your advice better be accurate.

This should be well known by now to financial advisors, but a good chunk of taxpayers did not get that memo. Tax returns for 2018 were the first under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which among numerous other provisions eliminated the ability to reverse a Roth IRA conversion. The tax bill on many 2018 Roth conversions was not what was expected due to poor tax projections. That was understandable because it was tough to compare two different tax systems (the 2017 and 2018 tax laws). There were many parts of the 2017 tax law that were dramatically changed or eliminated in 2018. Even CPAs got caught flatfooted on this and really did not see the true tax effect until the tax return was prepared the following year, when, of course, it was too late.

This year will be a bit easier to project the tax effect of a Roth conversion since we can use the 2018 tax return to compare assuming most other income and deduction items are relatively similar. But still, there are items that continue to confound the best projections.

5 Of The Most Misunderstood Tax Effects Of Roth Conversions

These are the factors that can still throw off your 2019 tax projections. Some of these items unexpectedly increased the tax cost of the Roth conversion but some can actually reduce the tax bill, creating an opportunity to capitalize by converting more funds than might have been planned.

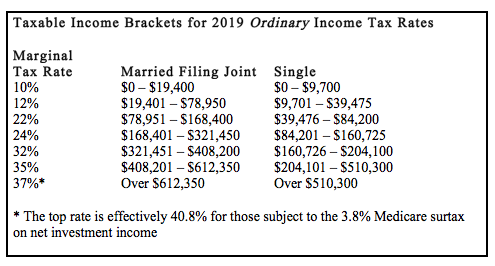

1. Capital Gains—This one is not new, but the larger more favorable capital gains tax brackets left some thinking that a good portion of their long-term capital gains (LTCGs) would fall under the zero percent bracket and escape taxation. Not so! This was not the case for most Roth converters because each dollar of ordinary income (like Roth conversion income, wages, interest, etc.) reduces the benefit of the zero percent capital gains rate. Under the tax law, ordinary income is taxed first using up the lower LTCG brackets. Anyone with other income besides LTCG receives little or no part of the zero percent LTCG rate, so don’t count on that for your tax projections. Of course, you can always offset these stock gains by harvesting losses. It can also pay to put off taking large gains in the same year as a Roth conversion, and instead take those gains in a future year when ordinary income might be lower, For example, if most IRA funds are converted to a Roth IRA, at age 70½ RMDs will be substantially reduced lowering taxable ordinary income, and allowing more LTCG income to fall into the lower LTCG brackets.

2. 20% QBI Deduction (Qualified Business Income)—This one first appeared on 2018 tax returns and still has tax planners baffled, but only when income exceeds the threshold limits.

The 2019 QBI Taxable Income Limits:

• $321,400 to $421,400 for married-joint

• $160,700 to $210,700 for single filers.

Most small business clients with pass-through income (from LLCs, S Corps., partnerships and sole proprietorships) fall under these limits so they all receive the 20% tax deduction, aka “the 199A deduction” named after that section of the tax code.

A Roth conversion though can throw a monkey wrench into the mix. A Roth conversion can push taxable income over the QBI limits and cause the 20% deduction to be lost. On the other hand, due to one of the other quirky QBI deduction rules, a Roth conversion can actually increase that deduction.

The QBI deduction in general is 20% of business income from any of these pass-through entities, if it doesn’t exceed the QBI limits. The deduction, unlike most others though does not reduce AGI. It reduces taxable income. But another tax rule lowers the QBI deduction if taxable income (in excess of capital gains) is less than QBI. In this case, a Roth conversion can increase taxable income and in turn increase the QBI deduction. But you must be careful not to convert so much that it throws income over the limit where the deduction can be lost altogether. This is a delicate balancing act.

Once income exceeds the QBI limits, other complex tax rules apply including the type of business, W-2 and capital investment tests which can knock out or allow the 20% tax deduction. That deduction becomes more valuable when business income is higher, so this is important to assess for pass-through business income clients, especially those close to the QBI income limits. If the client already does not qualify for the QBI deduction, due to the type of business or level of income, then the Roth conversion will have no effect since the deduction was lost even before the conversion.

3. Medicare IRMAA Charges (Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount)—These should be known to most advisors and clients, but the interplay with Roth conversion income is often confusing due to the 2-year lookback rule. In addition, for 2019, a new IRMAA charge income bracket was added for higher income Medicare enrollees. That income bracket ($500,000 and above for singles; $750,000 and above for married-joint) increases the IRMAA charges. However, the 2-year rule makes this more difficult to project the IRMAA effect on a Roth conversion. The IRMAA charges are based on income from two years ago (that income—MAGI—includes tax-exempt interest and untaxed foreign income). The 2019 limits apply to 2017 income, which already happened. A Roth conversion in 2019 won’t impact the IRMAA charges until 2021. If IRMAA charges will be an issue for a higher income client, then you need to plan two years ahead to see how a 2019 Roth conversion (along with other 2019 income) will impact IRMAA charges in 2021.

4. Child Tax Credit Effect—Elimination of the personal exemptions made it hard to predict how replacing these exemptions with a new child tax credit would net out. A tax credit is more valuable than a tax deduction since the tax credit reduces the tax dollar for dollar, so on its face it would appear that for some clients, the tax credit might cut the tax bill more than the personal exemptions did, unless you don’t qualify.

The credit is $2,000 per qualifying child, but this credit only applies to children under age 17, subject to the income limits ($400,000 joint, and $200,000 for all others). The tax credit for children over age 17, and other dependents is only $500. While the child tax credit can certainly reduce the tax on a Roth conversion (unless the conversion is so large that it pushes income over the limits), for some taxpayers it turned out that the lost exemptions exceeded the benefit of the tax credit, unexpectedly increasing the cost of the Roth conversion. Now that advisors can look at the completed 2018 tax return, the impact of children and other dependents on a 2019 Roth conversion can be more accurately projected.

Another child-related change is the so called “Kiddie Tax.” A child’s unearned income will no longer affect the parent’s tax return. The child will pay the tax, if applicable, on his own tax return at trust and estate tax rates. This is one of the few items that the tax law truly simplified. It will be a bit easier to project the tax on a Roth conversion for parents who no longer must include the child’s income on their tax returns. This change might lower the tax bill on conversions for these parents.

5. Alimony, New For 2019, No Deduction, But Tax Free To The Recipient—Beginning for 2019 divorces, alimony will no longer be deductible, and alimony received is no longer taxable income. Pre-2019 alimony arrangements are not subject to these new rules, unless they opt in.

Unlike many other TCJA provisions, alimony stands apart in two ways. First, while most other TCJA changes took effect in 2018, this one takes effect in 2019, so this year will be the first for clients who are subject to the new alimony tax rules. Second, this tax change is permanent. Most other TCJA changes expire after 2025.

How can this change impact Roth conversions? Two ways: The client paying the alimony cannot count on the alimony tax deduction to offset Roth conversion income, and the spouse receiving alimony income might be able to convert more since the alimony income won’t be taxable. Since 2019 was the first year for this change, this will only affect those clients divorced in 2019, and those who elected to have the new rules apply to their pre-2019 arrangement. This is just something to keep in mind when projecting the tax bill on a 2019 Roth conversion for recently divorced clients.

In addition to the above list, there are the usual items that advisors should consider when projecting the tax on a Roth conversion. For example, year-end bonuses, other one-time spikes in income or deductions, any tax benefit, deduction, credit or other provision tied to income levels, such as medical expenses (10% of AGI limit for 2019—new for 2019), the entire array of education credits and deductions and real estate losses among others.

The 3.8% tax on net investment income can also be triggered by a Roth conversion. The Roth conversion itself is not subject to the 3.8% tax, but it can raise income to the point that the 3.8% tax will apply to the investment income, where it didn’t without the conversion. This should also be looked at when projecting the tax on a Roth conversion.

Bottom Line

The point here is that advisors will have to be more precise in projecting the tax on Roth conversions since they cannot be undone. Using a tax-planning program can be very helpful here since it will take all these considerations into account. But as is the case with all software, it’s only as good as your input. Working with the clients’ CPAs or other tax advisors can also be worthwhile. Either way, the client still needs the tax impact explained ahead of time. That’s why it’s called “planning.”

Also, conversions should be done later in the year when many of these factors and income levels can be better known. For some strange reason, this planning is not being sufficiently addressed by most tax preparers, leaving the tax surprise to be disclosed the following year when nothing can be done about it. This is a high-value planning opportunity for financial advisors to act on now. It can also be a reason for clients to refer others each year.

Ed Slott, CPA, is president of Ed Slott and Company LLC. He is a recognized retirement tax expert and author of many retirement focused books. For more information on Ed Slott, Ed Slott’s 2-Day IRA Workshop and Ed Slott’s Elite IRA Advisor Group℠, please visit www.IRAhelp.com.